Metro Los Angeles is home to the largest population of Vietnamese outside of Vietnam. About two-thirds of the metropolis’s population lives in Orange County — home to the nation’s oldest and largest Little Saigon. Los Angeles County, on the other hand, has the third-largest population of Vietnamese-Americans but one which is less than half the size of Orange County’s. It also lacks an enclave like Little Saigon and the population is much more diffuse. Furthermore, whereas Vietnamese comprise more than 6% of Orange County’s total population, in Los Angeles they constitute less than 1% of the population. For these reasons, I suspect, this large and vibrant community tends to be overshadowed by the larger Orange County Vietnamese community.

The history of Vietnamese-Americans begins not (as is the case with many Asian communities) with the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 but rather with the end of the Vietnam War (Kháng chiến chống Mỹ) a decade later. Of course, prior to the end of that conflict, there were occasionally Vietnamese who came to the US hoping to improve their lot. Hồ Chí Minh, for example, lived and worked in New York City and Boston in 1912 and ’13. The numbers of Vietnamese who settled in the US, however, were small. By 1974, a mere 650 Americans of Vietnamese origin were registered as living in the country.

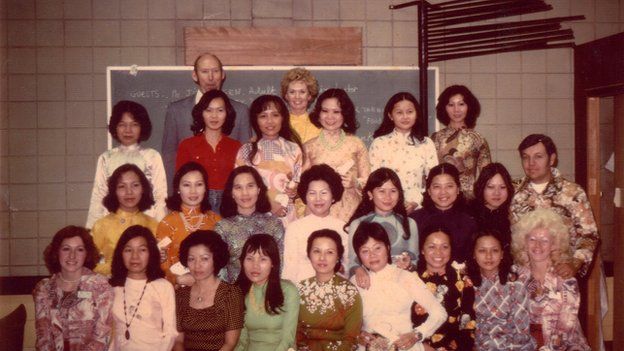

The first wave of significant Vietnamese migration began on 30 April 1975 with the fall of Saigon to the North Vietnamese. That event, which marked the official end of the Vietnam War, simultaneously marked the beginning of a mass exodus from Vietnam. The first wave of refugees — the so-called 75-ers — numbered about 175,000. Most were members of Vietnam’s urban middle and upper classes, were Catholic, and/or had close ties to American forces — all of which meant that remaining in Vietnam meant likely facing “re-education” or retribution. Many spoke English with a degree of fluency and the US was eager to ensure their speedy assimilation. Toward that end, the incoming Vietnamese were processed at four processing centers spread across the country: Elgin Air Force Base (Florida), Fort Chaffee (Arkansas), Fort Indiantown Gap (Pennsylvania), and Camp Pendleton (San Diego County). It was hoped that by spreading out the refugees that no Vietnamese enclaves would coalesce — but as Americans, many Vietnamese exercised their right to live where they chose and in many cases that was California.

In 1978, another wave of Vietnamese refugees began arriving in the US. The 78ers included not just ethnic Vietnamese but many Hoa (華 in Mandarin, literally “Chinese”), and other ethnicities (Cham, Khmer, Hmong, Tai Dam, Tai Dón, &c. Vietnam, far from being homogenous, is a multi-ethnic state. In Vietnam, 54 ethnicities are officially recognized by the Vietnamese government. In contrast to the 75ers, most of the 78ers were rural poor, Buddhist, and rarely spoke more than a few words of English. Also unlike the 75ers, who were airlifted out by American government forces, most 78ers haphazardly fled Vietnam in small boats and when they were rescued were pulled from the sea, which led to their being nicknamed “boat people.”

More waves of Vietnamese migration to the US followed the passage of the United States Refugee Act of 1980 and the 1988 passage of the American Homecoming Act. As of 2017, there were 2,104,217 Americans of Vietnamese ancestry, making them the fourth most numerous Asian-American population following Chinese, Filipinos, and Indians. California, of course, has by far the largest population of Vietnamese-Americans — 647,589 as of the last census — or 37% of the country’s entire population. San Jose has the largest population of Vietnamese of any American city. Westminster, Garden Grove, and Fountain Valley — all in North Orange County — are the American cities with the largest percentages of Vietnamese-American residents.

As of the 2010 census, Los Angeles had a Vietnamese population of 87,468. The relatively small suburb of Rosemead has the largest percentage of Vietnamese — about 8,401 — or 15.4% of the population. In contrast to the Vietnamese of Orange County, however, those in Rosemead are much more likely to identify as Hoa than they are ethnic Vietnamese (Việt or “Kinh” as they are officially known in Vietnam to differentiate them from minorities). San Gabriel has the second-largest Vietnamese population in Los Angeles County — some 2,524 — or 6.3% of the population. Just as with Rosemead, many of San Gabriel’s Vietnamese identify as Hoa.

The story is similar in the San Gabriel Valley’s suburbs with substantial Vietnamese populations: South San Gabriel, Alhambra, Monterey Park, El Monte, South El Monte, and Avocado Heights. In all but Avocado Heights, Vietnam is the second-most-common country of origin for the cities’ foreign-born but Mexican and Chinese were identified by the census as the most common ancestries. All — except Avocado Heights — are also home to large populations of ethnic Chinese born in mainland China — as well as smaller numbers from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Burma, Indonesia. To me, it’s illustrative of the flaws of the census — or at least of its inability to adequately paint a picture of the ethnic complexity of the region.

One of the best-known stories of an Hoa immigrant in Los Angeles County is the story of David Tran, the businessman whose ubiquitous Huy Fong hot sauce is synonymous with (for most non-Thai people, anyway) sriracha. Tran was born in Vietnam in 1945 (the year of the rooster – hence the logo) and fled Vietnam in 1978 aboard a Taiwanese freighter called the “匯豐” (Huìfēng — hence the name). After a short time in Boston, he settled, in Los Angeles’s Chinatown, the southern end of which was then first transforming into an enclave within an enclave. From his Chinatown base, he began making hot sauce — first using serranos — in 1980. Later, serranos were replaced with jalapeños and in 1987 operations moved to a larger warehouse in Rosemead. In 2010, following the wholesale adoption of the sauce by the American mainstream, operations again relocated to an even larger facility in Irwindale, which is now something of a tourist attraction.

In 1982, Penelope McMillan wrote about the growing Hoa population of Chinatown for a Los Angeles Times piece titled, “It’s Chinatown, with subtitles.” In it she noted, “Over the last few years, Chinatown has become a magnet for Vietnamese refugees, particularly those of Chinese extraction” and elaborated that there were then about 50 Vietnamese-operated stores in the neighborhood, about twice as many as the year before and expected to nearly double the following year. Of the roughly 16,000 people then estimated to live in Chinatown then, McMillan claimed that 10,000 were “said to be Vietnamese.” The vibe was, additionally, according to the reporter, “reminiscent of Southeast Asia street life” and she compared it to Cholon (Chợ Lớn), Saigon’s “Chinese District.”

McMillan wrote that many Hongkongers and Taiwanese, whose presence in the neighborhood predated the Vietnamese influx, these new residents were widely regarded as aggressive, unsanitary, and impolite “foreign intruders.” There were also complaints that the new arrivals were willing to work longer hours for lower wages. Predictably, too, they were blamed for an uptick in crime. Of course, immigrants and refugees being blamed for crime, bad manners, and job theft is obviously nothing new but I’m curious what outsiders made of these tensions — if they made anything of them at all.

It seems that there was an increase in crime and some of it, surely, was perpetrated by the Vietnamese — just as surely as some of it was perpetrated by non-Vietnamese. That the Vietnamese influx was also largely responsible for reinvigorating Chinatown seems to have been less frequently acknowledged and it’s possible that without them, Chinatown would’ve faded just as Little Italy and Frenchtown had before it — especially as many Chinese and Taiwanese were then leaving the neighborhood for the suburban comforts of the San Gabriel Valley.

Whatever tensions apparently existed, most Hoa seemed more eager to live and do business in Chinatown, not Orange County’s Little Saigon. McMillan quoted Vincent Siu-Cong Ly (who operated a supermarket, headed the America Vietnam Chinese Friendship Association, and published the Vietnam-Chinese/Yuehua bao newspaper) as saying “We want to be in a Chinatown more than in a Viet Town.” That many Hoa, despite their company of origin, felt a stronger connection with people of their own ethnicity is hardly surprising, especially when many fled Vietnam precisely because their Chinese ethnicity made them targets of hostility.

Of course, they were also no doubt aware that signs in Little Saigon were repeatedly defaced by Orange County snowflakes triggered by the existence of a non-European enclave in their midst. They were also likewise aware of a petition circulated by Westminster right-wingers who urged their city government to “deny granting any license to any Indochinese refugee attempting to set up any business in this Viet town [Little Saigon] area.” As anyone who’s been to North Orange County can surmise, their xenophobic petition was denied and Little Saigon today absolutely dominates the region (along with its smaller neighbors — Little Arabia and Little Seoul) but it probably required a relatively thick skin to suffer decades of unneighborly hostility.

Meanwhile, in Los Angeles there was, according to several sources, a group of Vietnamese businessmen were around that time trying to create a rival Viet Town (some sources say “Vietnam Town”) to compete with Little Saigon. I’ve yet to locate any primary sources, though, or even determine where this Viet Town was intended to form. I, therefore, don’t know who these businessmen were and whether or not they were Hoa — not that it would’ve necessarily entered into the equation — but half-Chinese Frank Jao, responsible for developing much of Little Saigon, weathered his fair share of angry protests over the design of his proposed developments by Vietnamese who regarded them as too Chinese.

I also don’t know where Viet Town was to have been located. Most Los Angeles Vietnamese businesses were then situated in the southern end of Chinatown… but establishing an enclave within an enclave is a tricky prospect — just as the Bangla promoters of Little Bangladesh, an enclave located within Koreatown. Beyond Chinatown, in East Hollywood, there was also a small cluster of Vietnamese businesses operating just east of what would later develop into Thai Town. If that was the location, there’s no sign of it today.

The Viet Town planners apparently envisioned something more than just a commercial corridor or shopping district or, “more than a Bolsa Mini Mall” as one source put it. Viet Town, it seems, was intended to be a full-fledged community, with residences and businesses. Although hard to imagine now, the gulf between Orange County and Los Angeles County’s Vietnamese communities was apparently then not as great as it is now. According to the Los Angeles Times, there were about 350 Vietnamese businesses in Orange County and about 250 in Los Angeles.

Perhaps Viet Town was planned for somewhere in the San Gabriel Valley. In the 1970s, realtor and investor Frederic Hsieh had begun successfully promoting Monterey Park to wealthy investors in Taiwan, portraying — however unlikely — the then mostly white, middle class, mid-20th-century suburb as the “Chinese Beverly Hills.” Immigrants came from Taiwan as well as Hong Kong duly transformed the community in the 1980s into a mostly Asian one. In 1983, Tianjin-born Lily Lee Chen was elected mayor. Whether it was more Beverly Hills or Baldwin Hills could be debated but it was definitely Chinese. Then again, even that only hints at the nuances of origin and identity. Joining the Hong Kongers and Taiwanese were Vietnamese and Chinese from Vietnam. Many of Monterey Park’s wealthier Taiwanese relocated to nearby upscale communities like Arcadia and San Marino — or to newer, more isolated suburbs like Hacienda Heights, Rowland Heights, and Walnut. In the wake of Taiwanese flight, the Mandarin in Monterey Park took on a mainland accent and Teochew overtook Hokkien.

Whatever and wherever the planners had in mind for Viet Town, it never happened, although the San Gabriel Valley suburbs with the largest Vietnamese communities all form all neighbor one another, suggesting something of a dispersed suburban enclave within a larger Chinese one. It’s not the only Vietnamese pocket in Los Angeles County though, there are also substantial numbers of Vietnamese in the nearby Eastside neighborhood of Lincoln Heights — located midway between Chinatown and the San Gabriel Valley. There’s also a small but visible concentration of Vietnamese in the inland South Bay, mostly in Alondra Park and Lawndale.

VIETNAMESE ANGELENOS

About half of all overseas Vietnamese (Người Việt hải ngoại) are Vietnamese Americans (Người Mỹ gốc Việt). Some prominent Angelenos of Vietnamese heritage who are either currently or formerly Angelenos include activists Cindy Trinh, Jane Nguyen, Katie Kalvoda, Kenny Uong, and Trinity Tran; astronaut Eugene Hữu Châu Trịnh; astrophysicist Xuân Thuận Trịnh; athletes Anh-Dao Tran, Jim Parque, and Lee Thế Anh Nguyễn; business people: Amy Doan (Sugarpill Cosmetics), David Tran (Huy Fong Foods), Ellen Nguyen (UnitedOther), Eliza Nguyen (Guest), Tom Nguyen, and Tuan Nguyen; chemist Thuc-Quyen Nguyen; judge Jacqueline Hồng Ngọc Nguyễn; martial artist Du Au; mass transit planner Tham Nguyen; perfumer Linda Sivrican (Capsule Parfumerie; photographer Darah Trang, poker players David Pham, Mến Văn “The Master” Nguyễn, and Thithi “Mimi” Tran; politicians Janet Nguyen and John Tran; radio producer Vivian Le (99% Invisible), slebs Jeannie Camtu Mai, Thien “Tila Tequila” Thanh Thi Nguyen, and Tyga; and supercubers Minh Thái.

VIETNAMESE FILM AND VIETNAMESE ANGELENO FILMMAKERS

The Cinema of Vietnam began in the 1920s, when a group of intellectuals formed the Huong Ky Film Company in Hanoi. Internationally, perhaps, the best-known Vietnamese filmmaker is Trần Anh Hùng (Cyclo, The Scent of Green Papaya, and Vertical Ray of the Sun). Film students such as myself are probably familiar with the didactic, experimental films of Trịnh Thị Minh Hà.

Metro Los Angeles is or has over the years been home to quite a few Vietnamese film figures. Perhaps the best known is Marseille-born actress France Nuyen (born France Nguyễn Vân Nga) who appeared in South Pacific and the Broadway version of The World of Suzie Wong. In 1968, as Elaan of Troyius, she shared an interracial kiss with Captain Kirk on Star Trek, although less is made of it, for whatever reason, than his interracial kiss with Lieutenant Uhura. She also appeared in the films The Last Time I Saw Archie (1961) Satan Never Sleeps (1962), A Girl Named Tamiko (1962), Diamond Head (1963), Dimension 5 (1966), Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973), and The Joy Luck Club (1993).

In the 1980s, Dustin Nguyen and Jonathan Ke Quan were famous for their respective roles as Harry Truman Ioki on 21 Jump Street and Short Round in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. James Duval notably appeared in several of Gregg Araki‘s films in the 1990s. Maggie Q and Olivia Munn appeared in numerous projects in the 2000s and after. Other Vietnamese Angeleno actors include An Phan, Anna Thu Nguyenova, Cat Ly, Christopher Dinh, David Hyun, Hanh Nguyen, Hiệp Thị Lê, Kathy Uyen, Kelly Marie Tran, Kiều Chinh, Lana Condor, Leanne Huynh, Quyen Ngo, Sophia Tran, Thuy Trang, Tim Dang, Tina Duong, and Xanthe Huynh. Vietnamese Angeleno filmmakers include Annie Huang, Bao Nguyen, Brian Su Nguyen, Đoan Hoàng, Elizabeth Ai, Hàm Trần, Linh Nga, Mai Pham, Nadine Truong, Quynh Ong, Steve Nguyen, and Thien A. Pham. Vietnamese Angeleno stand-up comedians (and in some cases, actors), include Ali Wong, Andy Van, Dat Phan, Karen Tong, Patti Harrison, and Rosie Tran. Models (and sometime actresses) include Karrueche Tran and Kim Lee.

VIETNAMESE MUSIC AND VIETNAMESE ANGELENO MUSICIANS

Traditional Vietnamese music arose out of indigenous traditions developed by the countries numerous ethnic groups and interactions with the musical traditions of China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia. There are folk traditions (e.g. ca trù, dân ca, hát chầu văn, hát xẩm, hò, and quan họ) and court music traditions (e.g. nhã nhạc, nhạc lễ, and ca Huế). There is a musical theater tradition, chèo. 19th and 20th century developments include nhạc tài tử, nhạc đỏ (red music), and nhạc vàng (yellow music). The diasporic Vietnamese community brought the world the “overseas” scene and Vietnamese New Wave.

- Vietnamese Angeleno musicians and DJs include Anh Do (aka Ann Do), Arigato Grande (Jenny Ly), Ashley Nguyen Dewitt, Bao Vo (Ming & Ping), Chau-Giang Thi Nguyen, DJ/artist DemonSlayer (Dan Nguyen), DJ Lani Love (Lani Nguyen), Don Hồ, Emily Ryan (Emily’s Sassy Lime), Henry Chuc, Jenny Dang, Khánh Ly, Mai Hương, DJ/recording engineer Quang Nguyen, Sandra Vu (SISU), Stella Tran, Tóc Tiên, The Uptight, and Vicky Farewell.

- There are many more Vietnamese Orange Countian musicians (mostly singers), including Anh Tu, Bang Chau, Billy Shane, Carol Kim, Công Thành & Lyn, Duy Quang, Hoang Lan, Hương Lan, Julie Quang, Kenny Thái, Khánh Hà, Kim Ngân, Khoa Van Le, The Lac Hong, Lam Anh, Lệ Thu, Lê Uyên & Phương, Leyna Phương Nguyễn, Lilian Christensen, Lưu Bích, Luu Hong, Lynda Trang Đài, Nhu Mai & the Magic, Ngọc Anh, Ngan Khoi Chorus, Nghiêm Phú Phi, Ngọc Bích, Ngọc Lan, Ngoc Nguoi, Nhat Truong, Như Loan, Nhu Mai, Phạm Duy, Phi Nhung, Philip Huy, Phương Hồng Quế, Phượng Liên, Phuong Mai, Quynh Huong, Sher’e Thu Thuy, Son Ca, Thai Chau, Thai Hien, Thái Thanh, Thái Thảo, Thanh Hà, Thiện Khiêm, Thiên Phú, Thiên Trang, The Thuy Duong Quartet, Thúy Vi, Tiếng Tơ Đồng, Tô Chấn Phong, Tommy Ngô, Trần Thái Hòa, Trish Thuy Trang, Trizzie Phương Trinh, Trường Hải, Tu Quyen, Tuấn Anh, Tuấn Ngọc, Vũ Công Khanh, Ý Lan, and Ý Nhi.

VIETNAMESE ART AND VIETNAMESE ANGELENO ARTISTS

Vietnamese art has a long and rich history stretching back to roughly 8,000 BCE. Whilst retaining distinctly Vietnamese characteristics, Vietnamese art has been profoundly influenced by Chinese art since at least the 2nd century BCE. By the 19th century CE, French art was another major influence.

Vietnamese artists who live or have lived in Metro Los Angeles include Amanda Hua, An Le, Anh Nguyen, Ann Phong, Boone Nguyen, Brian Pham, Christine Nguyen, Cindy Trinh, Dan Nguyen, Emily Ryan, Hon Hoang, Huyen Dinh, Jackie Khanh Doan, Julie Hang, Karen Tong, Leann Huynh, Thanh Vu, and Vincent Than. Vietnamese Angeleno designers include Huyen Dinh and Victoria Vu

VIETNAMESE LITERATURE AND VIETNAMESE ANGELENO WRITERS

In Ancient times, imperial Annam was dominated by China and much early literature of the period was in Hanese. Chữ nôm, created around the 10th century CE, allowed writers to compose in Vietnamese using native characters. When the quốc ngữ script was created in 1631, it was limited primarily to Christian missionaries until the early 20th century. Today, nearly all works of Vietnamese literature are written in the script.

Vietnamese writers who’ve at called Los Angeles home include Evyn Lê Espiritu Gandhi, Nguyễn Chí Thiện, Jackie Lam, Jennifer Ly, Mai Nguyên Đỗ, Thanhhà Lạ, Thuc Doan Nguyen, Nguyễn Thanh Việt, Teresa Mei Chuc, and Tien Nguyen. Metro Los Angeles has also been or is home to Vietnamese poets Diana Khoi Nguyen, Du Thu Le, and Lynn Nguyen Boland. Vietnamese journalists who’ve lived in Los Angeles include Jean Trinh, Kim Bui, Leyna Nguyen, Mary Nguyen, Nguyễn Hoàng Doãn, Nick Ut, and Vicky Nguyen. Former food writer C. Thi Nguyen was also an Angeleno.

VIETNAMESE NAIL SALONS

Of course, for every Vietnamese celebrity, there are many who, though visible, can’t reasonably be characterized as public figures. It’s impossible to imagine that any reasonably observant Angeleno wouldn’t notice at some point, even if they don’t patronize them, that most employees of nail salons are Vietnamese. By now it’s a fairly well-known story that actress Nathalie Kay “Tippi” Hedren visited a Vietnamese refugee camp, Hope Village, where she hoped to find work for the camp’s women. The women in the camp expressed interest in the manicure business and Hedren’s beautician was brought to the camp. Soon after, a group of twenty women earned their cosmetology licenses. It obviously didn’t stop there — today the majority of America’s nail technicians are Vietnamese.

VIETNAMESE FESTIVALS

There are several festivals important in Vietnamese culture. The most important is Tết Nguyên Đán, the lunar new year often shortened to “Tết” (or referred to as “Chinese New Year” despite being additionally observed in Korea, Mongolia, Taiwan, Tibet, and historically, Japan). There are annual Tết Nguyên Đán observances in Orange County’s Little Saigon but, as the date is also observed by the much larger Chinese and Taiwanese populations of the San Gabriel Valley, public celebrations there tend to be less specifically-Vietnamese. That said, The L.A. Tet Festival was launched in 2003 and in the past has taken place (without apparent annual consistency) in Rosemead and South El Monte. From my personal experience, it seems that many more Los Angeles Vietnamese use the occasion of Tết to celebrate privately with family and friends.

Other prominent Vietnamese festivals include Tết Trung Nguyên (Wandering Souls’ Day), which falls on the fifteenth day of the seventh lunar month, and Tết Trung Thu (Children’s Day/the Mid-Autumn Festival), which falls on the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month. On Tết Trung Nguyên; clothes, food, and money (all made of special paper) are prepared for wandering ancestral souls. On Tết Trung Thu, children participate in parades with lion dancers and drums. Just because I’ve not experienced either firsthand, however, doesn’t mean that they’re not celebrated locally. The Vietnamese bakery near my residence is always well-stocked with bánh trung thu around that time of year.

VIETNAMESE RELIGION

Officially, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam is an atheist state. However, as of 2014, 73.1% of Vietnamese were classified as either non-religious or following a Vietnamese folk religion (mostly Đạo Dừa or Đạo Mẫu) — a strange grouping, to be sure. 12.2% of Vietnamese were classified as Buddhist (mostly Pure Land, Bửu Sơn Kỳ Hương, Hòa Hảo, and Tứ Ân Hiếu Nghĩa), 7.6% Christian (6.9% Roman Catholic and 1.5% Protestant), 4.7% Caodaist, 1.4% Hoahaoist, and .1% “other.” As is often the case with immigrants, however, Vietnamese-Americans are much more likely to identify as Christian than their homeland’s counterparts. According to one survey, 30% of Vietnamese-Americans, identify as Catholic and 6% as Protestant. According to the same survey, 43% of Vietnamese-Americans practiced Buddhism.

I’ve never attended any Christian church service in Los Angeles but I’ve seen several churches that offer sequential sermons in English, Spanish, and Korean — the languages spoken by most of the area’s non-Orthodox Christians. I gather that some churches offer Sunday services in Vietnamese as well. Neither have I been to a Buddhist service but I likewise gather that some are specifically Vietnamese whilst others have nuns and monks fluent in Vietnamese, Chinese, and English. I’ve attempted to include them on the map but I’m sure I’m missing quite a few and obviously, any additions or corrections are encouraged.

VIETNAMESE CUISINE

Vietnamese cuisine is one of the world’s major cooking traditions (shouts out to Mekong and Saigon to Bangkok — both in Coralville, Iowa — for introducing me those many years ago). Over centuries, indigenous traditions have mixed with foreign influences which are filtered through a culinary philosophy of ngũ vị to create dishes that can stand side by side with the world’s best. For reasons I don’t understand, most non-Vietnamese diners seem content to limit their Vietnamese culinary experience just to phở. Nothing against phở, of course (except for the bad puns it inspires) but eating only phở is a bit obscene — like going to Italian restaurants and never ordering anything by biscotti.

Phở restaurants thus dominate the contemporary Vietnamese restaurant landscape — especially in neighborhoods with smaller Vietnamese populations who may love phở but don’t want to make it their life. I strongly suspect that most of Koreatown’s phở restaurants — like that neighborhood’s sushi restaurants and French cafés — are owned and operated by Koreans and probably mostly serve Koreans (or at least non-Vietnamese Angelenos). Just as I have nothing against phở, I have little use for authenticity and would therefore never take issue with non-Vietnamese cooking or eating Vietnamese food. I would, however, attempt to gently persuade you to try something else on the Vietnamese menu at least once in your life.

Phở, for the unfamiliar, is a breakfast soup consisting of broth, bánh phở (phở noodles), herbs, and typically beef (although chicken and vegetarian versions are also popular. The vegetarian version is sometimes humorously referred to as “phở không người lái”). It originated, in its current form, in northern Vietnam in the 1910s. Its popularity spread to southern Vietnam following the 1954 Partition of Vietnam when many Vietnamese relocated from the north to Saigon. Several sources claim that the first American phở restaurant opened in Orange County in 1980 — although I’ve yet to see mention of the restaurant’s name. I don’t doubt it, though; by then there were more than a dozen Vietnamese restaurants in Los Angeles. A piece by Salli Stevenson titled “Savory Spreads, Saigon Style,” appeared in the Los Angeles Times in 1980 in which the writer mentions not just phở but bánh cốm, bánh cuốn, bánh phu thê, cà ri gà, chả giò, gà nướng sả, gỏi cuốn, gỏi gà, and súp măng cua — perhaps suggesting that diners 40 years ago were more adventurous than today’s insufferable “foodies.”

A distant second in popularity (in my estimation) is bánh mì. Although the name literally translates to “wheat bread,” it’s understood by context to refer to a specific type of sandwich prepared on a baguette which is generally dressed with cilantro, cucumber, pickled carrots and daikon, jalapeños, mayonnaise, Maggi sauce (“ma zi”), and other fillings. As with phở, it was traditionally eaten as a breakfast dish. Unlike phở, though, bánh mì assumed its current form in Saigon in the 1950s and rather than spread north spread to the US with refugees.

Despite both being white and having once embarked on a promising career in my teens at Blimpie, I’m not that much of a sandwich guy. I appreciate a nice grilled cheese but I’ve never had a French dip, lobster roll, or pastrami on rye — and never will. I do like bánh mì (chay), though. Something about the combination of flavors and textures tugs at the stomach — and not, in most cases — the wallet. My first was at Lee’s Sandwiches, a now-international chain that began as a food truck in San Jose in 1981 at which some bánh mì snobs might look down their noses. I reckon it’s pretty good, though, and some locations sell fried vermicelli and dưa chua so that you can experiment with your own at home. I also like Bánh Mì & Chè Cali (usually referred to simply as Bánh Mì Chè Cali) — another chain, albeit one which started closer to home (Orange County). Sadly, my favorite, Baguette Express, closed in 2007 and the only Asian grocery store in Mideast Los Angeles (A-Grocery Warehouse) closed so now I go to Kiên Giang Bakery in Echo Park.

Today, many of Los Angeles’s best vegetarian restaurants are also operated by Vietnamese. Dien Phan opened the region’s first vegetarian Vietnamese restaurant Viên Hướng, in Little Saigon, in 1990. Pham Bang followed suit in 1991, with The Eight Immortals of Tao, also in Orange County. The first vegetarian Vietnamese-owned restaurant to open in Los Angeles was Bodhi Garden 菩提園素菜館, which opened in Angeleno Heights in 1992. I don’t believe that there are any locations of Loving Hut currently in operation in Los Angeles but there are several locations of One Veg World. The woman behind both vegan chains is Supreme Master Ching Hai, the Vietnamese cult leader of the Ching Hai World Society (清海世界會) which, for reasons unknown to me, is especially popular in Taiwan. That said, in Southern California, you’re much more likely to encounter one of her acolytes at a Vietnamese function than, say, a Taiwanese night market. They’re pretty benevolent, as cult members go — usually, they’ll just offer you a reusable shopping bag and urge you to adopt a vegetarian diet (which we probably all should).

There are currently hundreds of Vietnamese restaurants in Los Angeles and dozens of more non-Vietnamese restaurants which nevertheless include a Vietnamese option here and there. I’m thus not going to bother mentioning and linking to them. I have, however, attempted to map as many as I can come up with — both past and present. If I’ve missed any (or included any that shouldn’t be), please leave a comment. Oh, and I will mention a few Vietnamese food trucks both for the sake of completism and because they’re by nature a bit hard to pin down on a map. There’s Banh Duc Ngoc Hoa, Cafe Vietnam Truck, Mandoline Grill Truck, and SaiGon Corner. Ăn Nam and Nom Nom Truck are no longer in business. Notable Vietnamese Angeleon chefs and restaurateurs include Christine Huyen Tran Hà, Diep Tran, Khanh N. Hoang, Natasha Phan, and Ngan Thieu

VIETNAMESE TRANSIT

With “No Enclave,” I don’t usually talk about mass transit because the focus of the series is on diffuse communities. It is interesting, however, to look at the map and see where Vietnamese businesses are focused. You could certainly hit a lot of them by traveling along Main Street, Valley Boulevard, and Garvey Avenue in the San Gabriel Valley. Those are served by Metro‘s and 78, 76, and 70 lines, respectively.

I’m including a section on transit in this piece, however, primarily as an excuse to discuss Xe Đỗ Hoàng, a low fare, private shuttle service which serves an almost exclusively Vietnamese clientele and connects communities with substantial Vietnamese populations in California (El Monte, Los Angeles, Oakland, Sacramento, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, and Westminster/Little Saigon) and Arizona (Chandler, Phoenix, and Tempe). The shuttles depart and arrive in the parking lots of bánh mì restaurants (i.e. Ban Le, Huong Lan, and Lee’s) or Vietnamese markets (i.e. ABC, Lam’s, and Thuan Phat). Included with the fare is a bottle of water and a bánh mì — which is why the shuttle is often referred to as the “bánh mì bus.”

Here’s a playlist for your adventures in Vietnamese Los Angeles and beyond. Tạm biệt!

FURTHER READING

“Strangers in a Strange Land — But Happy” by Dham Huynh, Los Angeles Times, 25 December 1980

“Business and politics in Little Saigon, California” by Nam Q. Ha (2002)

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, Los Angeles County Store, the book Sidewalking, Skid Row Housing Trust, and 1650 Gallery. Brightwell has been featured as subject in The Los Angeles Times, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, and on Notebook on Cities and Culture. He has been a guest speaker on KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, at Emerson College, and the University of Southern California.

Brightwell is currently writing a book about Los Angeles and you can follow him on Ameba, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Mubi, and Twitter.

13 thoughts on “No Enclave — Exploring Vietnamese Los Angeles”