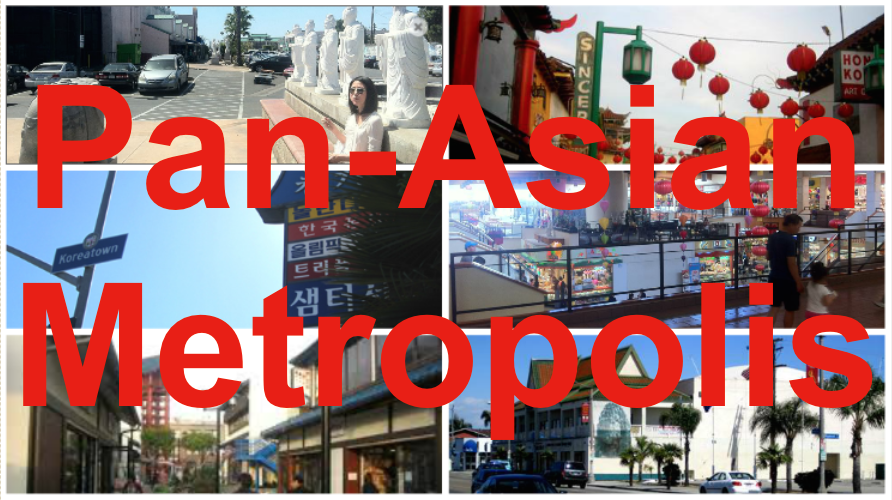

There were Asian-American architects working outside of Los Angeles. Thomas S. Rockrise (né Iwahiko Tsumanuma) joined the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1921, toward the end of his career. Yasuo Matsui followed in 1927. In the mid-20th century, there Asian-American architects active in other parts of the country, as well, including Edith Leong Yang, Pu Hu Shao, and Theresa Hsu Yuen (1964). There were also Asian architects who worked in Los Angeles. Chinese architect I.M. Pei designed the Century Towers (1965, Century City) and the Creative Artists Agency building (1989, Beverly Hills). There were also Asian-Americans from outside Los Angeles active in Los Angeles, like Detroiter Minoru Yamasaki, who designed Century Plaza Hotel (Century City, 1966) and Century Plaza Towers (Century City, 1975). Comparatively little attention, however, has been thus far paid to Los Angeles’s own pioneering Asian-American architects.

The focus of this piece is on early Asian-Angeleno architects who lived and worked in Los Angeles and in doing so contributed to the city’s built environment in the most literal sense. They also paved the way for subsequent organizations like the Asian American Architects and Engineers Association and later Asian-Angeleno architects like Alice Fung (of Fung + Blatt), Annie Chu (of Chu-Gooding Architects), Barton Choy (of Choy Associates), Cara Lee (of leeMundwiler) Daveed Kapoor, Franklin Sata, Hayahiko Takase, Joseph Kitashama, Kevin Tsai, Kian Goh, Ko Kiyohara (of Kiyohara Moffitt), Leo Yuen Park, Mark Lee (of Johnston Marklee & Associates), Robert and Blossom Uyeda (of Tetra – IBI Group Architects), Roger M. Yanagita (of Roger M. Yanagita Associates), Roger Sai-keung Hong, Ronald Chang, Rupert Mok (of Rupert Mok & Architects), Shoji Shimizu, Ted Tokio Tanaka (Ted Tokio Tanaka – Architects), Toshikazu Terasawa, Yunsoo Kim, and many others.

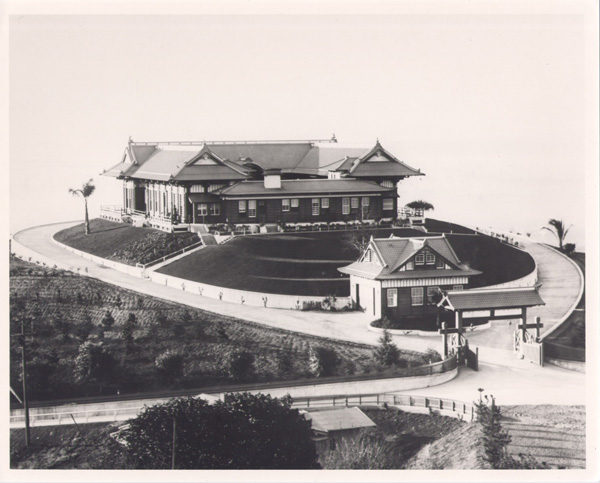

Before there were working Asian-American architects, Asian-inspired architecture was solely the product of the non-Asian imagination. Adolph and Eugene Bernheimer, two Jewish cotton importers from New York, called their massive home in the Hollywood Heights, “Yamashiro,” and claimed inspiration came from a mountain fortress they’d seen in Kyoto. Sid Grauman‘s Chinese Theatre was designed by Raymond M. Kennedy of the architectural firm of Meyer & Holler.

Much of Chinatown was built from discarded set pieces previously used in the yellowface Hollywood epic, The Good Earth. When incorporated into Chinatown, they joined a landscape populated by restaurants, grocery stores, shopping centers, movie theaters, and homes meant to evoke Ancient Egypt, Bavaria, the Maya homeland, Morocco, New England, New Orleans, Normandy, Olde England, Spain, Switzerland, and other “exotic” locales.

There were more sophisticated attempts to incorporate Asian architectural influences into an indigenous style of local architecture. The California Craftsman homes of the late 19th and early 20th century drew inspiration from English, Japanese, Mexican, Scandinavian, Swiss, and Chinese architecture and design. There’s a Craftsman home at 2384 Silver Lake which plays up the Chinese influence more than most but built in 1913, it was almost certainly the creation of a non-Chinese architect.

The Modernists also drew from Asian influences. Frank Lloyd Wright spent several years employed as an architect in Japan. His Robie House, in Chicago, built in 1909, shows a strong Japanese influence, and inspired locally-active Modernists like A. Quincy Jones, Craig Ellwood, Gregory Ain, Lloyd Wright, Paul R. Williams, Pierre Koenig, R. M. Schindler, Richard Neutra as well as several of the Asian-American architects who are the subject of this piece.

The Asian architect community was small for several reasons. Given the existence of discriminatory laws — which precluded Asian Angelenos from owning property or naturalizing as citizens — opportunities to design buildings were rare. Most were limited to institutional buildings rather than residential or commercial. Sei Fujii (1882-1954) challenged Alien Land Laws when he tried to buy a home in City Terrace and the case went to the Supreme Coury. The result of Fujii v. California and Masaoka v. California was the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952, which formally ended the exclusion of Asians in US immigration policy and thus allowed Asian-Americans to own property. This supreme court decision, in turn, increased the opportunity for Asian-Angeleno architects, many of whom were afterward commissioned to design homes and businesses for Asian-Angeleno clients.

DAISUKE DIKE NAGANO

Daisuke Dike Nagano was born in 1921. He was a student of architecture at USC. After the forced relocation and incarceration of Japanese-Americans in concentration camps, Nagano was employed as a “supervising architect” at the notorious Manzanar camp. A 1943 edition of the Manzanar Free Press reported that Nagano had been relocated to New Haven, Connecticut, where he received a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Yale in 1944. He later attended Harvard and went on to join the AIA. He designed Modernist homes, such as one in Venice (1116 Berkeley Drive), built in 1957. In 1957, Nagano collaborated with Kazumi Adachi on the Fort Moore Pioneer Memorial, a large stone memorial wall built in 1957 on part of the original location of Fort Moore. He also designed the Crenshaw Square Shopping Center, built in 1959, which served as a beacon for Japanese-Americans who settled in the Crenshaw District after World War II. He later collaborated with Richard Neutra’s firm on the Capitol Tower and Garden Apartments in Sacramento. In 1962, he designed the building for Northrop Architectural Systems. He died in 1965.

DAVID HYUN

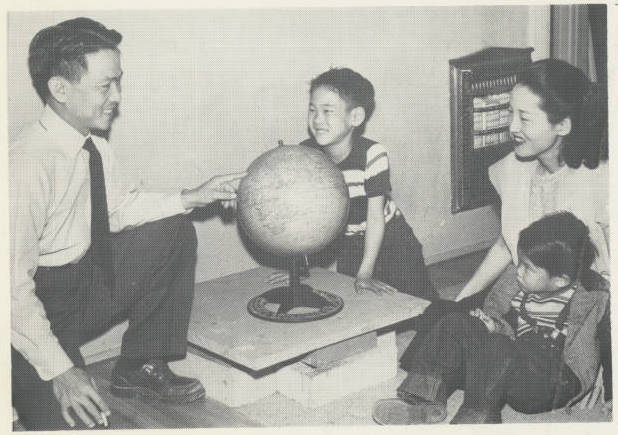

David Hyun was the first Korean-American architect. He was honored by the Japanese-American Citizens League, co-founded the Leadership Education for Asian Pacifics (LEAP), and chaired the board of directors of the Korean-American Coalition (KAC). He was the subject of pieces in the Los Angeles Times, Architectural Digest, and House Beautiful. He was also a fan of chess, golf, and photography.

David Hyun was born in Japanese-occupied Korea in 1917. His father, the Reverend Soon Hyun, was actively involved in the Korean resistance and the Hyun family, like many Koreans, fled to China after the Japanese crackdown which followed the public display of resistance known as the March 1st Movement or Sam-il. The Hyuns lived in Shanghai for five years, where Reverend Hyun helped organize the Korean Provisional Government before relocating to American-occupied Hawaiʻi. Hyun graduated from the University of Hawaii in 1940, with degrees in math and physics.

Hyun, his wife Mary, and their two sons (David and Than) moved to Los Angeles in 1947. Hyun studied architecture at the University of Southern California (USC) whilst working as a janitor. He also continued working as a union organizer, something he’d done begun in Hawaii. This — and the fact that his father had strongly criticized American-backed dictator, Syngman Rhee — led to Hyun’s being labeled a “dangerous alien” and in 1949 the Hyuns were detained on Terminal Island on charges of violating the Alien Registration Act. The Los Angeles Civil Rights Congress, the Los Angeles Committee for Protection of the Foreign Born, fellow architects and members of the then-small Korean-American community successfully organized to prevent his and his family’s deportation. In 1958 the US government again designated him an undesirable, this time charging him with violating the McCarran Internal Security Act. Again, organized resistance prevented the Hyuns’ deportation.

Hyun founded his own firm, David Hyun Associates, Inc. in Glendale in 1953. The firm’s logo was designed by James and Tomoko Miho. Hyun designed several beautiful modernist homes including the Lawrence Segal House (3626 Cadman Drive, Los Feliz, 1955), the Tapelband Residence (1910 Lucile Avenue, Silver Lake, 1957), the Haddad Residence (1958), his own Hyun Residence (west San Fernando Valley, 1960), the McTernan House (2226 Wayne Avenue, Los Feliz, 1960 — Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 1065), the home at 300 South Rossmore (Hancock Park, 1961), and the Nisser Residence (Downey).

His most famous project was the CRA-backed “revitalization” of Little Tokyo. The Japanese Village Plaza and Yagura Fire Tower were designed by Hyun in 1978. The blue, sanshu ceramic roof tiles that cap the buildings were later incorporated into the new residence he built for his family in Silver Lake in 1993 (1954 Redesdale Avenue).

David Hyun died in 2012, a year after his wife of seventy years. He was 95 years old.

EUGENE CHOY

Eugene Choy was the second Chinese-American architect to join the AIA and the first in Southern California. He was also featured in the exhibition, Breaking Ground: Chinese American Architects in Los Angeles (1945-1980).

Eugene Kinn Choy was born in Guangdong in 1912, to Kinn Choy and Shee Wong. He moved to the US, with his family, in 1898. His family settled in Bakersfield where they sold blue jeans to Central Valley farmhands.

Choy studied architecture at the USC where he also served in the Architecture School Student Senate. He graduated in 1939 and in 1941 married Lucille Fong in 1941. The couple had two children, Barton and Reece. From 1943-1945 Choy worked for Hughes Aircraft Company, in Culver City.

In 1947, Choy founded the architectural firm, Choy Associates and the year after, the US Supreme Court ruled the enforcement of racial housing covenants unconstitutional, those opening up many suburbs to non-whites. Choy built several residences in the Primrose Hill area of Silver Lake, including his own at 3027 Castle Street (1949). Nearby he also built the homes at 3200 Windsor Avenue (1954), 3022 Windsor Avenue (1956), and 3028 Windsor Avenue (1956). In 1953, he also built the Chew Residence (3893 Franklin Avenue, Franklin Hills), one of several Chinese-American clients for whom Choy designed homes. Sometimes he collaborated on projects with his brother Allan, such as the FBI Office Building in Las Vegas (1961). His son Barton followed in his footsteps, becoming an architect and working at his father’s firm.

Choy also worked on commercial and institutional projects, such as the Cathay Bank in Chinatown (777 North Broadway, Chinatown, 1962), which incorporated Chinese elements into a New Formalist design. In 1975, Choy designed the nearby Castelar School (840 Yale Street, 1975).

Choy died in 1991, aged 78.

FRANKLIN SATA

Franklin Sata was born in 1933 to celebrated Japanese Angeleno painter and photographer, James Tadano Sata, and his wife, Joshie. They named after Franklin D. Roosevelt. After Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, Franklin Sata and his family were sent to Jerome War Relocation Center. After Jerome was turned into a camp for German prisoners of war, the Satas were sent to the Gila River Detention Center. Sata graduated from USC with a Bachelor of Architecture degree in 1960. He designed the Sakaida Residence in South Pasadena in 1978 Ken Sakaida, a dentist who worked in the Eastside.

FRED HIFUMI

Fred T. Hifumi was born on 1 April 1928, to Chiyo and Ray Hifumi. As a child he lived in East Hollywood. During World War II, he was interred at Manzanar and was later a member of the Manzanar Committee with wife Sadie (Inatomi) Hifumi. He was issued his architect license in 1963. He designed the headquarters for the Southern California Gardeners Federation, built at 333 South San Pedro Street in 1970. Today he lives in Culver City.

GILBERT LEONG

Gilbert Leong was an architect, co-owner of Chinatown’s Soochow Restaurant, longtime member of East West Bank’s board of directors, and member of several other organizations. He was featured in Lisa See’s book, On Gold Mountain: The 100-Year Odyssey of a Chinese American Family, a CBS documentary about Chinese-Americans, and the exhibition Breaking Ground: Chinese American Architects in Los Angeles (1945-1980).

During World War II he served in the US Army. After the war’s conclusion he worked for architect Paul R. Williams, who inspired him to serve his Chinese-American community in much the same way as Williams had done the black community, by building stylish (although often understated) houses in newly desegregated suburbs. One example of a Leong residence is the home at 2410 West Silver Lake Drive (1957).

Leong’s commercial designs were generally more fanciful than his residential ones. In Chinatown his designs include the Chinese United Methodist Church (825 N Hill Street, 1947), the First Chinese Baptist Church Los Angeles (942 Yale Street, 1951), the Bank of America (850 North Broadway, 1971), and the Kong Chow Benevolent Association and Temple (931 North Broadway, 1960), where he also served as director. He also designed the charming courtyard of the Pacific Asia Museum (46 North Los Robles Avenue) in Pasadena.

He died in 1996, aged 85.

GIN WONG

More than the other architects of this piece, Gin Wong is known primarily for large corporate, institutional, and retail projects. He was recognized by Getty Center’s Pacific Standard Time initiative and has been honored by the Los Angeles Conservancy’s Modern Committee. He was also chief of the Architectural Guild for the School of Architecture and Fine Arts at USC.

Gin Dan Wong was born in 1922 in Guangzhou, China and immigrated with his family to Los Angeles in the 1930s. In 1942 he began studying engineering at Los Angeles City College before serving in World War II as a B-29 navigator in the Army Air Corps. After the war he studied architecture from USC, graduating in 1950.

After graduation, Wong worked at the firm of Pereira and Luckman, eventually becoming vice president of design. While there he designed CBS Television City (7800 Beverly Boulevard, Fairfax District, 1952). In 1958, he co-founded William L. Pereira & Associates where he eventually assumed the role of the firm’s president. At that firm he worked on the design of Westlake’s Union Oil Center (1201 West 5th Street, 1958), LAX’s Theme Building (201 World Way, Westchester, 1961), and the Beverly Hills Union 76 Station (427 North Crescent Drive, 1965, ). In San Francisco, the firm was responsible for the Crocker Bank Tower (1966), Mutual Benefit Life building (1969), the St. Francis Hotel annex (1972), and the iconic Transamerica Pyramid (1972). In Honolulu, the firm designed the Pan Pacific Tower (1971).

Wong formed his own firm, Gin Wong Associates, in 1974. That firm’s designs include Arco Tower (1055 West Seventh, Westlake, 1989), the Crean Tower and Mary Hood Chapel (Garden Grove, 1990), and the Hyatt Regency Incheon (2003), among other projects. Wong and his GWA firm remain active today. (UPDATE: Gin Wong died in 2017, aged 94).

HAI C. TAN

Considering he was a member of the American Insititute of Architects; worked on projects throughout much of California, and was described by the Oxnard Press Courier in 1964 as “one of Southern California’s leading architects,” it’s perhaps surprising how little biographical information I’ve been able to find about Hai C. Tan. Nor have I been able to find any pictures of him.

Hai Chuen Tan was born around 1921 in Guangzhou and came to the US in 1945. He graduated from the University of Oregon. In 1963, he founded Hai C. Tan, Architect & Associates in Fullerton. In 1964, he was involved in several large residential projects in Oxnard and Aptos. In 1969, he designed the residence at 1933 Redcliff Street for Jack C. Lee, then the owner of Yee Sing Chong Company, a popular Chinatown market. In 1972, he designed Chinatown’s Mandarin Plaza for Lee, who’d in 1969 purchased the land on which had previously stood Advance Neon Sign Company and Thompson Boiler Works. The Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 was enacted on 30 June 1968 and opened the door for increased immigration from China. When it opened, Mandarin Plaza was the first of Chinatown’s major commercial “plazas” built since the 1950s and Tan designed the entrance to suggest a gigantic, gold ingot. He was still working at least as late as 1975, when he designed the townhomes of William Krueger‘s Whittier Monterey development in Whittier. Today he apparently lives not far away, in Hacienda Heights.

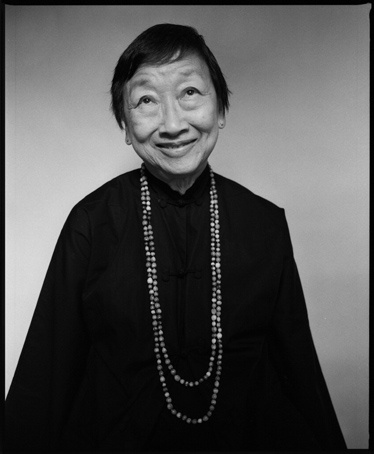

HELEN FONG

Helen Fong was a noted Modernist and Googie architect. She was honored in the exhibition, Breaking Ground: Chinese American Architects in Los Angeles (1945-1980). She also was reportedly an opera lover.

Helen Liu Fong was born in Old Chinatown in 1927. She graduated from the University of California, Berkeley with a degree in city planning in 1949. Afterward, she worked as a secretary for Choy Associates. In 1951 she moved to Armet & Davis, local Googie practitioners who showed Americans what diners and coffee shops were supposed to look like.

Norm’s instantly recognizable restaurants are found throughout Los Angeles’s suburban landscape. The first Norm’s was opened by Norm Roybark in 1949. The second location (470 North La Cienega Boulevard, Beverly Grove, 1957) was designed by Helen Fong.

A year later Fong designed an even more celebrated diner, Pann’s Coffee Shop (6710 La Tijera Boulevard, Westchester, 1958). Its mix of neon signage, jarring angles, terrazzo floors, flagstone walls, glass sheets, lush landscaping (by landscape architect Sid Galper) manages to evoke both the stone age and the future or, as Alan Hess put it in Googie: Fifties Coffee Shop Architecture, “where George Jetson and Fred Flintstone could meet over a cup of coffee.”

The Holiday Bowl (3730 South Crenshaw Boulevard, Leimert Park, 1959 – demolished) was a bowling alley, pool hall, bar (“Saki-ba”), and diner designed for five Japanese-American clients who constructed it at the corner of Crenshaw and Coliseum, center of a Japanese-American community in South Los Angeles’s Westside (See also: Not Bowling Alone: How the Holiday Bowl in Crenshaw Became an Integrated Leisure Space). The diner’s menu tellingly sold biscuits and gravy, chow mein, donburi, egg foo young, grits, hamburgers, hot links, pork noodles, saifun, salmon patties, short ribs, udon, and yakisoba. It closed in 2000 and was demolished in 2003, despite its inclusion on the Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument list. In its places is a shopping center which boasts a Big 5 Sporting Goods, a Verizon store, a Quizno’s, and other shopping center staples. The coffee shop portion was preserved, at least, and is now a Starbuck’s.

Helen Fong died of cancer in 2005 in Glendora, aged 78.

HIDEO MATSUNAGA

Hideo Arthur Matsunaga was born on 18 May 1924 in Sanger, California to Gunda and Sueno Matsunaga. He graduated from USC, along with his twin brother, Shigeto, in 1953. Shigeto went into dentistry whilst Hideo became an architect, first, with George Vernon Russell & Associates. One of Matsunaga’s most-celebrated home was one designed for a Japanese-American couple reminiscent of a Japanese country house, built in the South San Rafael neighborhood of Pasadena. In 1978, Matsunaga collaborated with Kiyoshi Sawano, Kiyoshi Sawano, Isamu Noguchi, and Takeo Uesugi in the design of the Japanese American Community and Cultural Center. He also worked for the Los Angeles Unified School District as Deputy Director of the Architecture and Engineering Division. He contracted COVID19 in 2020 and passed away on Halloween. He was preceded by his wife, Yuri, and was survived by his children Geoffrey, Carol, Keith, Jon, and Kim.

JOSEPH J. TAKAHASHI

Joseph J. Takahasi was born in 1925 and active in the Los Angeles area in the 1960s and ’70s. During World War II he was at the concentration camp in Poston, Arizona but in 1944 enlisted in the Ft Douglas Utah Military branch. He married a woman named Emiko and they had four children: Coleen, Gary, Julianne, and Linda.

Takahashi designed the Ferdin House (built in Los Feliz 1963), his own Takahashi Family Residence (1652 Elevado Street, Silver Lake, 1963), the offices of Wada & Asato Agency (3220 West Jefferson Boulevard, Crenshaw Seinan, 1966), the George and Ada Lee Residence (2448 Lyric Avenue, Los Feliz, 1971), and Venice Judo Dojo (12448 Braddock Drive, Del Rey, 1971/1972). He incorporated Joseph J Takahashi Inc in 1985 but died around 1987.

KAZUMI ADACHI

Kazumi Adachi was born in 1913. He graduated from USC in 1939. Kazumi had already designed Modernist homes, such as one in Ojai, by the time he founded Kazumi Adachi & Associates, in San Pedro, in 1953. Adachi designed Kay’s, a garden supply store located at 3318 West Jefferson Boulevard, in 1954. Adachi collaborated with Daisuke Dike Nagano on the Fort Moore Pioneer Memorial in 1957. In 1957, he also designed the New Shonien/Japanese Children’s Home at 1815 Redcliff Avenue. He designed another Modernist residence in 1958 for Mr. & Mrs. Lou Rifkin, in the Hollywoodland neighborhood. He designed the San Fernando Japanese American Community Center at 12953 Branford Street in 1959. Adachi designed his own home, the Kazumi Adachi house, in Beachwood Canyon. In 1969, he designed a stunning home in Granada Hills, overlooking the first hole of the Knollwood Country Club golf course, for a doctor and his family. In 1971, Adachi collaborated with Kiyoshi Sawano, Hideo Matsunaga, Isamu Noguchi, and Takeo Uesugi in the design of the Japanese American Community and Cultural Center. He died in 1992.

KAZUO NOMURA

Kazuo “Kaz” Nomura was born in 1921. He graduated from USC in 1951. He was an associate in A. Quincy Jones‘s firm. He died in 1978.

KENNETH NISHIMOTO

Kenneth Masao Nishimoto was born in Tokyo on 21 October 1907. He came to San Francisco in 1920. Nishimoto attended USC and was the president of the Japanese Trojan Club in 1933. He graduated with a Bachelor of Architecture degree in 1934. He was hired by architect William Henry Taylor. During World War II, Nishimoto was sent to the Gila River War Relocation Center where he and his wife, Kay, had a child — Diane Nishimoto. Nishimoto became an American citizen in 1953. Afterward, he co-founded the firm of Taylor, Warren, Nishimoto & Conner. He launched his own practice in 1957. That year, Nishimoto built his family residence in Pasadena‘s Poppy Peak neighborhood at 1525 Poppy Peak Drive. His Gregory Conway Residence in Fullerton was inspired by a Japanese palace. He designed the the Minka teahouse at Descanso Gardens in 1966 with landscape architect Eijiro Nunokawa. He died on died Halloween, 1992.

KI SUH PARK

Ki Suh Park was born in Seoul on 15 March 1932. He was the second of nine children born to Seung Man Park, an agricultural geneticist, and Haechung Im Park, a schoolteacher. Park emigrated to Los Angeles in March 1953 to study at East Los Angeles College. He earned his bachelor’s degree at UC Berkeley in 1957 and met his wife, Ildong, there. He later earned a graduate degree in architecture and city planning from MIT. In 1961, back in Los Angeles, he began working at Gruen Associates. He became a partner at the architecture firm in 1972 and a managing partner in 1981. He died, aged 80, in 2013.

KIYOSHI SAWANO

Kiyoshi Sawano was born in Shizuoka, Japan. He graduated from Waseda University in Tokyo in 1943 and went on to serve during World War II as an instructor in the Japanese Imperial Army. After working as a designer, he immigrated to the US in 1955 and first found work as a busboy. He married Yasuko Judy Sawano. In 1968, he founded Kiyoshi Sawano and Associates in Los Angeles. In 1981, he founded Sawano & Associates in Garden Grove and Newport Beach. Sawano collaborated with Kazumi Adachi, Hideo Matsunaga, Isamu Noguchi, and Takeo Uesugi in the design of the Japanese American Community and Cultural Center.

Kiyoshi Sawano died of cancer in 2007, at the age of 89.

SCHWEN WEI MA

Schwen Wei Ma was born in Shanghai on 30 January 1907. He became an American citizen on 11 April 1932. Wei Ma designed the home at 3018 Castle Street, Silver Lake, for New Chinatown co-founder Peter Soo Hoo, his wife, Lillie, and their family. It was built in 1952. It must surely have been his last project as he died on 10 January 1953. In 1957, it was modified by Gilbert Leong.

TOM TAKAHASHI

Tom Takeshi Takahashi was born 10 August 1932 in Los Angeles to parents from Japan. During the Second World War, he and his family were interned at the Colorado River War Relocation Center in Poston. He graduated from USC in 1960. He designed his own Takahashi Family Residence at 2351 Hidalgo Avenue (not to be confused with Joseph Takahashi’s family residence, also located in Silver Lake) and built it in 1966 and ’67. Takeshi co-founded Robinson & Takahashi with Mitchell Robinson in 1969. In 1973, they were joined by Herbert Katz and formed Robinson Takahashi, Katz & Associates – a firm that was focused on commercial, healthcare, and industrial design. He and his wife, Momoyo, and their daughter, Rena, seem to have moved to Cupertino in the 2010s.

Y. TOM MAKINO

Y. Tom Makino was born in 1907. He studied architecture at the USC School of Architecture where he obtained his Bachelor of Architecture in 1935. From 1935 to 1940, he worked as a designer-draftsman for the firm of Plummer, Wurdeman, & Becket. He opened his own practice in 1940. From 1942 to 1945, he worked for the War Relocation Authority in Arkansas. From 1945 to 1951 he worked for the firm of W.F. McCaughey and Associates. In 1948, he joined the American Institute of Architects. In 1955, he designed the West Los Angeles Buddhist Temple at 2003 Corinth Avenue. In 1956, he designed the West Los Angeles Japanese Methodist Church at 1913 Purdue Avenue. In 1957, he designed the Santa Monica Nikkei Hall at 1413 Michigan Avenue. In 1961, he designed the San Fernando Valley Hongwanji Buddhist Temple at 9450 Remick Avenue. In 1969, he designed the Hompa Hongwanji Buddhist temple at 815 East 1st Street in Little Tokyo. That same year, he designed alterations on Doris Duke‘s residence, Falcon Lair. He lived in Gardena and died in 1993 at the age of 85.

YOS HIROSE

Yos Hirose was born 4 April 1882 in Nagasaki, Japan. He immigrated to the United States in 1903. He began attending the Armor Institute of Illinois in 1911 and obtained a bachelor’s degree in architecture in 1915. Soon afterward, he moved to Los Angeles, where he began his career as an architect, draftsman, and engineer. He designed the Art Deco Japanese Hospital in Boyle Heights, built in 1929. He lived in Boyle Heights, then a largely Japanese suburb of Little Toyko, at 2607 Gleason Avenue. Ultimately, he designed several key Japanese institutions of the neighborhood, including the Japanese Baptist Church (1926-1929), Higashi Honganji (1926-1927), Tenrikyo Junior Church of America (1937-1939), the Konko Church (1937-1938), and the Rafu Chuo Gakuen Japanese Language School (1938). During the Japanese Internment, he lived in the concentration camp in Poston, Arizona. Hirose died in October of 1963 at the age of 1981.

YOUNG WOO

Young Woo was one of fifteen children born to “Asparagus King” Joesph Woo. After serving in the Korean War, architect Young Woo enrolled at Los Angeles City College. He transferred to USC and in 1958 became a member of Tau Sigma Delta, the national architecture honorary fraternity. In order to pay for his tuition, he took a job with architect Robert C. Duncan. Whilst still a student, Woo designed half a dozen homes for Modern Trend owner, developer Stan Martson. Upon graduating in 1959, he went to work for Richard Dorman. After Dorman, he worked briefly at both A. C. Martin and Associates, William L. Pereira Associates, and Morganelli-Heumann & Associates, the latter of which he was the lead architect for. His own Woo Residence, at 3763 Mayfair Drive, was finished in 1968. In the early 1970s, Woo formed Urbatec, which specialized in public housing projects for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Notable Urbatec projects include LA County Housing Authority Housing (1971) in Lancaster and Inglewood Meadows (1975).

Thanks to Michael Locke, who has written about and photographed several homes for the Silver Lake News and Steve Wong, who curated Breaking Ground: Chinese American Architects in Los Angeles (1945–1980) at the Chinese American Museum in Chinatown.

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, writer, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities — or salaried work. He is not interested in generating advertorials, clickbait, listicles, or other 21st century variations of spam. Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft & Folk Art Museum, Form Follows Function, Los Angeles County Store, the book Sidewalking, Skid Row Housing Trust, and 1650 Gallery. Brightwell has been featured as subject in The Los Angeles Times, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, and on Notebook on Cities and Culture. He has been a guest speaker on KCRW‘s Which Way, LA? and at Emerson College. Art prints of Brightwell’s maps are available from 1650 Gallery. He is currently writing a book about Los Angeles and you can follow him on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Click here to offer financial support and thank you!

So beautiful post eric

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a great piece. Thanks Eric.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Bob. Hope you’re well!

LikeLike

Really great list, thanks for gathering all this information in one place.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Eric and Marrikka for this well deserved tribute.

LikeLiked by 1 person