This blog entry is about the Los Angeles neighborhood of Little Tokyo. To vote for other Southern California communities to be the subject of further explorations, let me know which in the comments.

INTRODUCTION TO LITTLE TOKYO

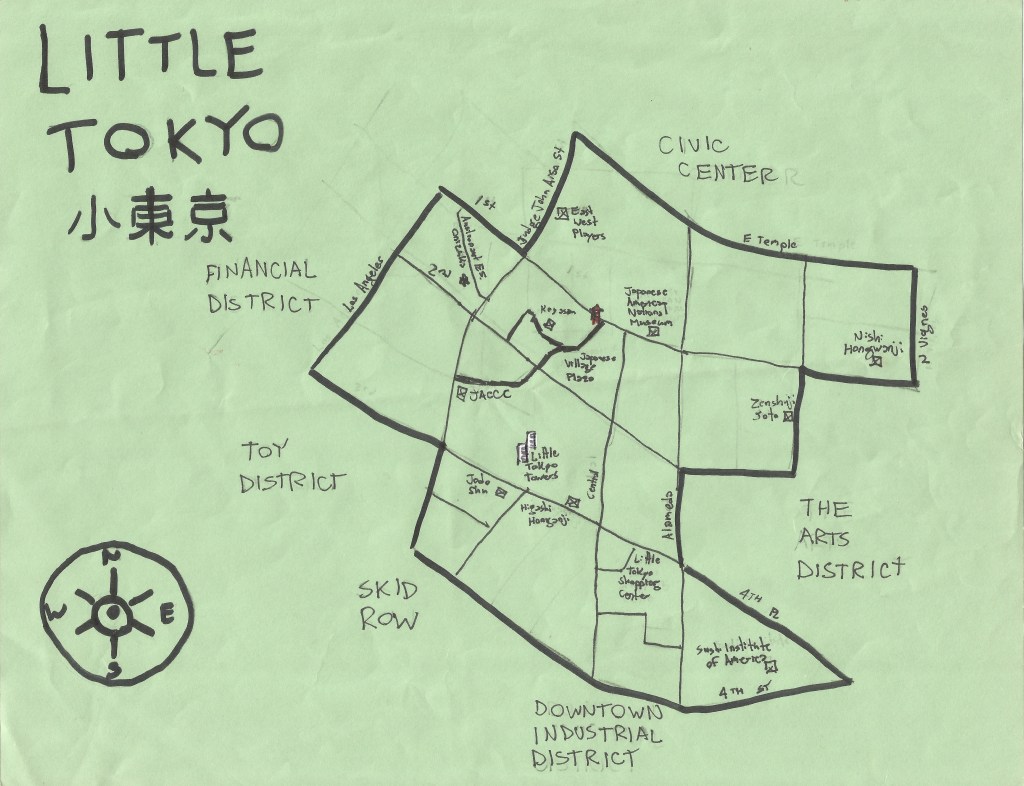

Little Tokyo (or 小東京) is a small neighborhood in Downtown Los Angeles. It’s generally considered to be bordered on the west by Los Angeles Street, on the east by Alameda Street, on the south by Third Street, and on the north by First Street.

Little Tokyo is neighbored by Boyle Heights to the east, the Civic Center to the north; the Financial District to the west; and Skid Row, the Toy District, and the Arts District to the south. As with many neighborhoods in Los Angeles, the borders of Little Tokyo aren’t officially designated. It used to be considerably larger and there remain many vestiges of the neighborhood’s more expansive past version beyond the current boundaries.

Lying outside — but within a few blocks of Little Tokyo — are Aikido-Aikibujutsu, City Cat Karaoke Studio, Fugetsu-Do, Ginza-Ya Bakery, Hana Ichimonme Restaurant, Hompa Hongwanji Buddhist Temple, Izakaya Honda-Ya Japanese Restaurant, Issendoki, Japan Arcade, Japanese Evangelical Missionary Society, Japanese Swordsmanship, Jodo Shu North American Buddhist, Kaigenro USA, Kato’s Sewing Machine, Kuragami Plant Boutique, LA Japanese Auto, Little Tokyo Car Wash, Little Toyko Cosmetics, the Little Toyko Library, Maryknoll Japanese Catholic, Mifune, Mikawaya, the former Mitsuwa Marketplace, Niitakaya USA Inc, Nishi Hongwanji Child Development, Shojin, Morten‘s beloved Sushi Go 55, Tajimi Pottery USA, Utsuwa-No-Yakata, and Zenshuji Soto Mission.

EARLY HISTORY OF LITTLE TOKYO

Today, as Little Tokyo’s Japanese-American population continues to age and dwindle in number, many have expressed concern about the possibility of the neighborhood losing its long-standing, historically Japanese character. That could happen, although Little Tokyo, like all Los Angeles neighborhoods, has undergone many demographic changes throughout its history. Regardless of the current and future makeup of the neighborhood’s visitors, residents, and business owners, for the time being, Little Tokyo’s Japanese-American character remains vibrant and rumors of the neighborhood’s demise seem comically premature. Although it may not be the draw for Japanese immigrants that it once was, at the very least it remains the cultural heart of the city’s Japanese-American culture and one of the most vibrant neighborhoods in the city.

EARLY HISTORY OF LITTLE TOKYO

The area now designated Little Tokyo in the past passed from the Tongva to the Spaniards to the Mexicans. After the US took over, many Chinese workers moved to the state of California. At the height of anti-Chinese racist sentiment, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882. As a result, many Japanese immigrated to the state to fill the void and many of the new arrivals settled in the eastern portion of downtown Los Angeles that soon became known as Little Tokyo.

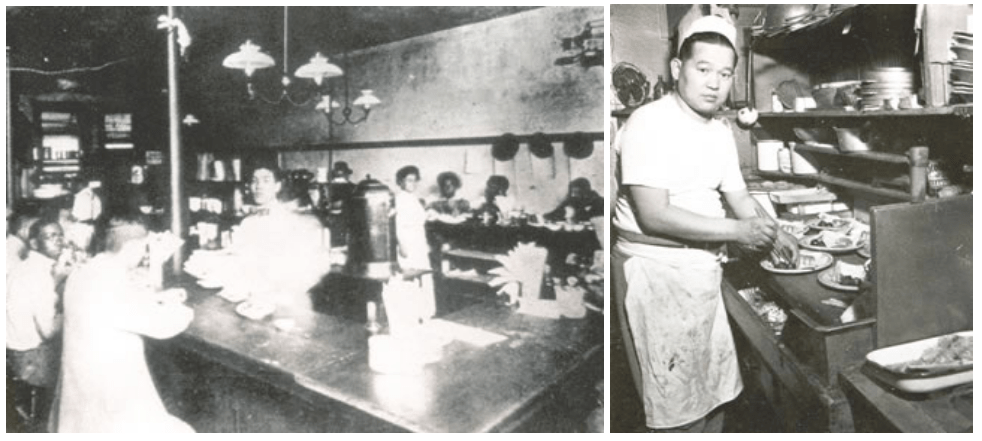

Accounts about the beginnings of Little Tokyo are hard to verify. According to one account, two Japanese, T. Kamo and I. Nosaka, immigrated to the area in 1869. A restaurant, Charlie Hama’s, was said to have been opened by a former seaman, Hamanosuke Shigeta, at 340 East First Street. According to another account, Shigeta’s establishment was actually on Jackson Street and opened in 1885. Another version of the story claims that the first Japanese-American business was a small restaurant near First and Los Angeles Street operated by another ex-seaman, known as Kame. Sorting out reality seems about as likely as figuring out how many licks it takes to get to the center of a Tootsie Roll Pop. Suffice it to say, some Japanese restaurants may have opened in the 1880s and were run, perhaps, by Japanese ex-seamen.

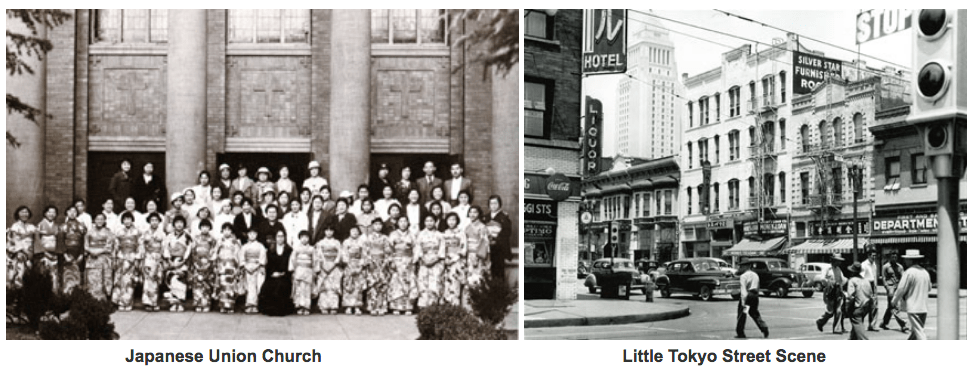

Almost immediately after the arrival of the first Japanese immigrants, the Japanese began to assert themselves. The Japanese Association of Los Angeles was formed in the neighborhood around 1890. In 1903, Rafu Shimpo, the first Japanese newspaper founded outside of Japan, was established. By 1905, the area was commonly referred to as “Little Tokyo.” After the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906, many Bay Area Japanese moved to Little Tokyo and across the river in Boyle Heights. 1907 was the peak year for Japanese immigration to the US, with 30,000 crossing the Pacific that year alone. By 1908, there were over forty Japanese-owned businesses along the two-block stretch on First Street between Los Angeles Street and Central Avenue. Reflecting the changing demographic, in 1911, the Hotel Empire became the Little Tokyo Hotel.

Little Tokyo has never been a homogenous neighborhood. In Little Tokyo’s early years, there were also large numbers of Chinese, black, and white residents as well. The latter two peoples were central to the birth of pentecostalism in the neighborhood, at the First African Methodist Episcopal Church Apostolic Faith Mission, founded in 1888. In 1906, at the Azsua Street Revival, 1,500 nutters jammed into what was essentially a wooden barn to be baptized by the Holy Ghost. Black preacher William Joseph Seymour and his white counterpart, Hiram Smith, preached about hellfire whilst musicians in the congregation banged on cows’ ribs, played washboard, and clacked thimbles. At one such revival, their congregation even included no less a hoity-toity character than Arabella Huntington, who was chauffeured all the way from posh San Marino. By 1909, racial tensions divided the formerly harmonious congregation and they split. The building was ultimately demolished in 1931.

Alarmed by increasing numbers of non-Chinese Asians, the Asian Exclusion Act was signed in 1924. By that time, the area on both sides of the Los Angeles River was home to about 30,000 Japanese-Americans. In Little Tokyo’s early days, most of the shops were clustered along East First Street. On the other hand, Central Avenue was home to many vegetable markets. Today, First Street continues to be the main commercial corridor and the sidewalk features a timeline of important dates in Japanese-American history as well as the names of past businesses that occupied the buildings.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI raided Issei associations for evidence of disloyalty. Even though to this day not one case of espionage has ever been proven against any Japanese-American, at the time roughly 120,000 Japanese-Americans were rounded up and shipped to concentration camps. Following their forced removal, roughly 40,000 black moved to the then-vacant Little Tokyo and the neighborhood became known for several years as Bronzeville.

When the Japanese internment ended, the neighborhood once again reverted to being a Japanese-American enclave, albeit on a much smaller scale. At that point, most Japanese-Americans instead chose to move to neighborhoods like Pasadena (rather than the historically Japanese neighborhoods in Boyle Heights, Compton, Gardena, Long Beach, Little Osaka, Monterey Park, San Pedro, and Torrance). As Japanese-Americans moved outside traditional ethnic enclaves, the number of officially designated J-Towns dropped from 43 to just three today (the other two being in San Franciso and San Jose). In Little Tokyo, the LTBA re-emerged to help develop and revitalize the neighborhood. Another group, the Los Angeles Japanese American Association, formed in 1947 to help protect Japanese-Americans from racially motivated discrimination and abuse.

REVITALIZATION OF LITTLE TOKYO

In 1970, however, the seven-block, 67-acre core of Little Tokyo was designated the Little Tokyo Redevelopment Project Area. By the late ’70s, as the Japanese economy grew, several new banks, shopping plazas, and hotels opened in Little Tokyo, bolstered by overseas investment, and the area began to revive economically. In 1978, the iconic Yagura Tower (aka The Japanese Village Plaza Fire Tower) was built as part of the revitalization effort. Due in part to the internment, the Japanese American community was highly politicized. Thus, even though Little Tokyo’s Japanese residents continue to decrease in number, the community has preserved the Japanese character of the neighborhood as a tourist attraction, community center, and shopping area. In 1986, Japanese-American community activists established First Street as a historic district. In 1995, Little Tokyo was declared a National Historic Landmark District.

CHARACTER OF LITTLE TOKYO

Unlike most of Los Angeles’ other ethnic neighborhoods, Little Tokyo physically reflects the neighborhood’s longtime residents’ background in its architecture. Though not limited to religious structures, it can be seen in Higashi Honganji, Jodo Shinshu, Koyasan Buddhist Temple, Nishi Honganji, Shingon, Soto Zen Temple, and the Zenshuji Soto Mission.

Besides the neighborhood’s architecture, the Japanese character of Little Tokyo is evinced by the many monuments to Japanese-Americans, including a monument to astronaut Ellison S. Onizuka, a mission specialist who died in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. Weller Street, formerly a stagecoach road from the Wilmington Harbor, was renamed Astronaut Ellison S. Onizuka Street in his memory — even though such a designation exceeds the city’s sixteen-letter street name limit. There’s also a monument called Righteous Among the Nations in honor of Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese consul to Lithuania before World War II. The Go For Broke monument commemorates Japanese-Americans who served in the US military during World War II, despite the extreme racial prejudice they faced. There’s also a statue of philosopher Kinjiro Ninomiya. In addition, there’s the highly suggestive Friendship Knot and many other works of public art as well.

Befitting a Japanese neighborhood, there are at least two lovely public Japanese gardens in the neighborhood — the James Irvine Japanese Garden (Seiryu-en) and the rooftop garden in the Kyoto Grand Hotel and Gardens (Gan iwashire) (formerly the New Otani). In addition, there are many impressive private gardens within the neighborhood that one can stare at appreciatively through fences.

KOREANIZATION OF LITTLE TOKYO

Many Angelenos have expressed paranoia about growing numbers of Koreans in the city and their perceived “takeover” of neighborhoods in the city. 40% of stores looted during the 1992 riots in South Los Angeles were Korean-owned. Online, some Midtown residents occasionally froth at the mouth when their historically white enclaves are accidentally referred to as being part of Koreatown. In 2009, when Mitsuwa Marketplace (the first and largest Japanese market in California) was purchased by Korean owners (and changed to Little Tokyo Marketplace), the response of many suggested the loss of a loved one rather than an ownership change. For the record, the Korean owners still stock Japanese products and in addition, there’s still Marukai Market and Nijiya Market.

With the presence of more Koreans in the neighborhood has come an increasingly Korean character. On a leisurely stroll through Little Tokyo, one encounters large numbers of Koreans and passes numerous Korean businesses such as Zip Fusion, Han’s Bibimbap, Keunsub Yun, Ko Hang Kim Bob, Korean Kitchen, Hankook Barbecue, Ock Sul Sun Sik USA Corporation, Park Je Myeong, Pinkberry, Sohoju, and Tofu Village. While their presence may be bemoaned by a segment of authenticity-obsessed Nipponophiles and cultural watchdogs (presumably ones who don’t live in the neighborhood), Koreans actually have significant ties to the neighborhood that stretch back decades and, following a decrease in overseas investments from Japan, the Koreans have done more than anyone else to invigorate the neighborhood. Even the Japanese Village Fire Tower and Plaza, the symbol for many of modern Little Tokyo, were designed not by a Japanese-American but rather by Korean-American architect David Hyun.

Not that there hasn’t been occasional tension between Japanese and Korean residents of the neighborhood. Japan, after all, is the birthplace of the Hate Korea Wave. When the growing Korean Angeleno population began reaching retirement age, many found themselves crowded out of nearby Koreatown and moved into the historically Japanese-dominated Little Tokyo Towers. Today, a third of the residents in the towers are Korean. But tensions have been eased largely due to the respectful efforts of the new population. Residents of the towers created a Korean-and-Japanese bilingual newsletter called Bridges. Korean residents also purchased a karaoke machine for the building, graciously adding 2,500 Japanese songs. A Good Neighbors committee was created specifically to dispense helpful hints to Koreans to help avoid conflict, with tips including not leaving kimchi jars in the hallways.

Outside the towers and around the neighborhood at large, many Korean business owners have also done their best to respect the Japanese character of Little Tokyo whilst necessarily accommodating the changing population, adding American, Chinese, and Mexican products to their shelves. In 2008, the Jana Korea Society mounted the Harmony Concert, at Union Church, which featured both Japanese and Korean music and dance.

The latest example of Korean-Japanese bridge-building is the Little Tokyo Korea Japan Festival, a joint production of The Korean Cultural Center, The Japan Foundation, and the Japan Korea Society. On 6 February 2010, they’re showing Hun Jang‘s Kim Ki-Duk-penned film, Rough Cut. There’s also a documentary about Little Tokyo called New Beginnings: Cultural Harmony in Little Tokyo — and the 2007 remake of Tsubaki Sanjuro. The event also is also scheduled to include live performances and is to be hosted by Asian-American actors James Kyson Lee (Heroes and Asian Stories (Book 3)) and Eriko Tamura (Heroes and Reaper).

HOLIDAYS AND FESTIVALS IN LITTLE TOKYO

Although the internment was the biggest blow to the Japanese character of Little Tokyo, as early as the 1930s Issei merchants began expressing concern that English-speaking Nisei were increasingly favoring nearby hakujin stores and turning their backs on their heritage. As a result, in 1934, the Downtown Japanese American Citizens League started the Nisei Week Festival, still held every August in the neighborhood.

In addition to Nisei Week, there are (or have been till recently) many other cultural expressions of Japanese culture in the neighborhood. From 1995 to 2007, the Los Angeles Tofu Festival was held in the neighborhood. Hinamatsuri is still celebrated every year, as is the Little Tokyo Concert & Food Fair every June. In the summer, Obon festivals continue to happen. In December, the Little Tokyo Community Mochitsuki is still widely observed.

JAPANESE RESTAURANTS

In fact, despite the concerns about the supposedly vanishing character of Little Tokyo, it is still very much represented by the incredible number Japanese restaurants, including Aoi Restaurant, Azalea, Curry House, Daikokuya, Daisuke Japanese, East, Ebisu Japanese Tavern, Frying Fish, Furaibo, Garden Grill, Gaya Tofu BBQ, Hama Sushi, Hanabishi, Hata Restaurant, Ichiban-Tokyo, Izakaya Haru Ulala, Izayoi, Joy Mart Restaurant, Kagaya, Kani Mura, Kappo Ishito, Orion’s beloved Kouraku, Koshiji, Kushi Shabu, Kushinobo, Maguro-Tei, Mako Sushi, Matsuki Japanese Noodle, Mitsuru Sushi & Grill, Mr. Ramen, Oiwake, Oomasa, Ngoc‘s beloved Orochon Ramen, Reikai’s Kitchen, Restaurant Imai, Restaurant Yutaka, Rokudan of Kobe, S & W Little Tokyo Ice Cream, San Sui Tei, Senka Café, Shabu Shabu House, Suehiro Café, Sushi Gen, Sushi Imai, Sushi Komasa, Sushi Teri, Takumi Restaurant, Tamon, Teishokuya of Tokyo, Tenno Sushi, Thousand Cranes, Tokyo Café, Toshi Sushi, Tot, Usui, Wakasaya, Yagura Ichiban, Yakitori Koshiji, Yamazaki Bakery, Yatai Japanese Kitchen,Yomochan, Zakuro Shabu Shabu, and ZenCu.

One such establishment, Fugetsu-do (which claims to be the birthplace of the fortune cookie), was founded in 1903 and today is the oldest still-operating food establishment the Los Angeles. Another, Mikawaya, founded in 1910, is still in operation and is well known for having introduced mochi to the US in 1994.

LITTLE TOKYO VS. LITTLE OSAKA

Although overall Little Tokyo seems more buttoned down and less hip — more salaryman and less otaku than Little Osaka, being a much larger neighborhood, Little Tokyo displays far greater diversity and is not without its share of youth-oriented businesses, as evidenced by the Little Tokyo establishments above.

DIVERSITY IN LITTLE TOKYO

Little Tokyo is still fairly diverse, in spite of the preponderance of Japanese and Korean establishments. In addition to the many Korean and Japanese restaurants in the tiny neighborhood, there’s Aloha Café, Azalea Restaurant & Bar, Cafe Cuba Central, Cafe Take 5, Capperi Restorante, Cefiore, Chin-Ma-Ya of Tokyo, Green Bamboo, Pho 21, Spitz, 2nd Street Café, Señor Fish, Tapas and Wine Bar, Via Dolce Café, Lars‘s beloved Weiland, and Wok Inn… and honestly way more than I care to mention.

ART IN LITTLE TOKYO

SHOPPING IN LITTLE TOKYO

Little Tokyo has several shopping areas that boast a large number of Japanese establishments including Weller Court, the Japanese Village Plaza, Honda Plaza, and the Little Tokyo Shopping Plaza.

Japanese culture has long been recognized for the way art infuses so many aspects of the culture. In Little Tokyo, shopping centers and even apartments are no exception. Right now, Heisuke Kitazawa (aka PCP) has examples of his art installed at Weller Court. Nearby, Nancy Uyemura‘s piece, Harmony, is a permanent fixture at Casa Heiwa.

In the shopping areas, there are stores like Kinokuniya and Video Paradise that specialize in Japanese-language videos and DVDs — ones that you would be hard-pressed to find, even in Amoeba‘s healthy Japanese DVD section. However, at Little Tokyo stores, many of the DVDs are NTSC-2 and the majority probably don’t have English subtitles.

VIDEO GAMES

Other shops and arcades in Little Tokyo carry and specialize in hard-to-find Japanese video games that you can’t even find at Amoeba! The exceptional Little Tokyo Arcade is no exception.

MUSEUMS AND THEATER

There are many theaters and museums focused on Japanese-American, Pan-Asian, and Asian-American culture in Little Tokyo, including the aforementioned Japanese American Cultural & Community Center, the Japanese American National Museum, and East West Players. The horribly-named ImaginAsian Center opened in December 2007, one of the first movie theaters to show mostly Asian films since the 2001 closing of the Garfield Theater in Alhambra. It closed after a couple years of operation.

LITTLE TOKYO AND FILM

Tsuru Aoki began her acting career on Toyo Fujita‘s stage in Little Toyko where she and Sessue Hayakawa often acted side by side before and after marrying in 1914. After being noticed by Thomas H. Ince, he placed her under contract. With a debut film performance in 1913’s The Oath of Tsuru San, she became one of the first Asian-Americans to appear on the silent screen. It was on her recommendation that Thomas H. Ince returned to the theater to attend a production of The Typhoon. Afterward, he offered its star, Hayakawa, a movie contract which led to his becoming the first Asian-American superstar in Silent Film.

The easily recognizable Yagura – Fire Tower is featured in a scene in Brother (2000) where Takeshi Kitano’s Yamamoto and Susumu Terajima’s Kato memorably try to forge an alliance with the strikingly handsome Masaya Kato’s Shirase – the yakuza boss of Little Tokyo (whose offices are apparently located within the National Center for the Preservation of Democracy). Other films shot in part or in whole in Little Tokyo include Batman (1943), Solar Crisis (1990), Showdown in Little Tokyo (1991), The Bodyguard (1992), Talk to Taka (2000), American Yume (2002), Girl with Gun (2006), MobiUS: A Little Tokyo Ghost Story (2009), and Sakura (2009).

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

41 thoughts on “California Fool’s Gold — Exploring Little Tokyo (小東京)”