a

In the spring of 2015, Una, Leonard, and I visited Glasgow, Scotland. I know that, had I had more time, I’d’ve liked to have also visited Edinburgh, Inverness, Orkney and elsewhere. In the past, I amused myself with the idea that on my first visit to the UK I’d skip England, instead limiting my explorations to Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and maybe Cornwall. It wasn’t mean to be, though, and my first visit to the UK began, like so many, in London, where we visited members of Una’s and Leonard’s family. Scotland, then, was a short side trip. With just a few days, it didn’t make sense to spread ourselves too thin, so we chose Glasgow, in part because Una is a fan of the city’s music scene and because I’m a fan of cities — and Glasgow is the country’s largest.

INTRODUCTION TO SCOTLAND

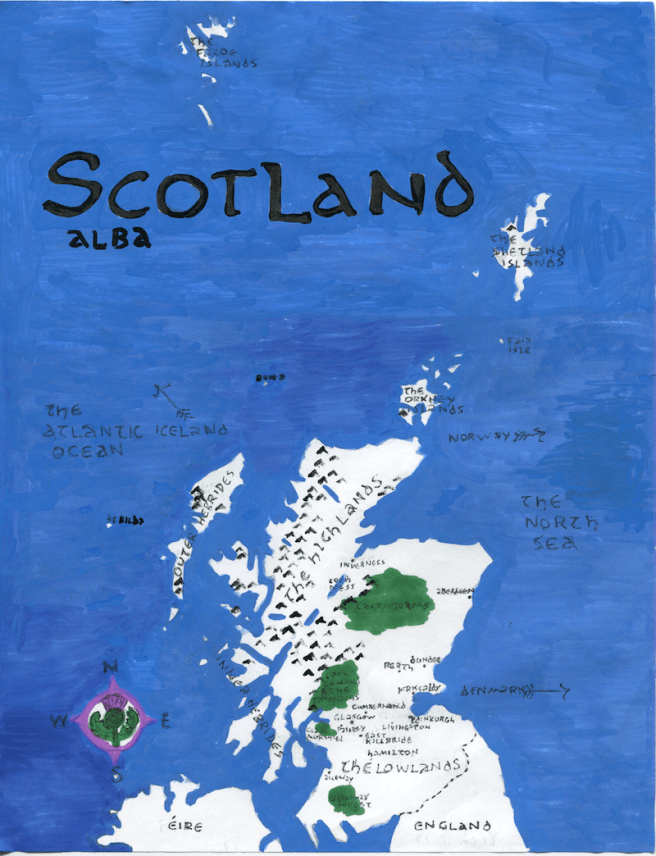

Scotland is a country which covers the northern third of the island of Great Britain. Its only land border is shared with England to the south. To the west, across the Irish Sea, is Ireland. To the north, across the North Sea, are Denmark and Norway. To the north are the Faroe Islands. In addition to the Scottish mainland, the country contains more than 790 islands, including the Northern Isles and the Hebrides, though fewer than 90 are inhabited by humans.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SCOTLAND

The first humans likely settled in what’s now Scotland toward the end of the last glacial period, around 9600 BCE, when retreating glaciers first made it habitable for humans. Scotland entered the Neolithic Era about 4000 BCE, the Bronze Age about 2000 BCE, and the Iron Age around 700 BCE. The recorded history of Scotland began with the northward expansion of the Roman Britannia. By the 1st century CE, Britannia reached as far north as the line between the Firth of Clyde and the Firth of Forth. The Romans referred to the country to the north as Caledonia, and its people as Picti, Latin for “the painted ones.” The painted ones constantly battled the Romans who famously built Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall to separate the two nations. First, the Antonine Wall was overrun and abandoned. Then, in 410, the Romans quit Britain entirely.

In the 6th century, later sources record that the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata was founded on Scotland’s west coast. In the 7th century, an Irish missionary named Columba established a monetary on Iona and introduced Christianity. The Viking Invasions began toward the end of the 8th century which prompted the Gaels and Picts to join forces in the 9th century when together they formed the Kingdom of Scotland.

Under Edward I, England launched a series of conquests on the Kingdom of Scotland, which led to the Wars of Scottish Independence, fought in the 13th and 14th centuries. The wars ended with England’s defeat, and under David II, Scotland was confirmed a fully independent and sovereign kingdom. The Kingdom of Scotland ceased to exist on 1 May 1707, when it joined the Kingdom of England to create the new Kingdom of Great Britain. In 1801, Great Britain, in turn, formed a new union with the Kingdom of Ireland, the United Kingdom of Britain and Ireland.

During the Scottish Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution, Scotland was one of Europe’s primary hubs of commerce, industry, and education. After World War II, it experienced a rapid industrial decline and since the 1950s, debates have frequently arisen around the subject of Scottish nationalism. In 1997, the Scottish Parliament was re-established. In 2014, a referendum on Scottish independence took place with 55.3% voting to stay in the UK and 44.7% voting to leave.

GEOGRAPHY & CLIMATE OF SCOTLAND

The total area of Scotland is 78,772 square kilometers, making it about the same size as the Czech Republic. Scotland can be geographically divided into three sections: the Southern Uplands, the Central Lowlands, and the Highlands and Islands. The country’s highest point is Ben Nevis, the summit of which rises 1,344 meters above sea level. The longest river, the River Tay, flows 190 kilometers from the slopes of Ben Lui to the Firth of Tay, south of Dundee. The agreeable climate is temperate and oceanic. Summers are cool and wet, with the highest recorded temperature being a tolerable 32.9°. Winters are comparatively mild as well, with the coldest recorded temperature of −27.2° having been recorded in the Grampian Mountains in 1895.

FLORA & FAUNA OF SCOTLAND

The flora of Scotland is typical of northwestern Europe. Before the widespread deforestation wrought by humans, Scotland was largely covered with vast deciduous and coniferous woodlands. Millenia of human activity has denuded much of the native Caledonian Forest although 84 remnants remain, including within the 4,530 square kilometer Cairngorms National Park, established in 2003. On the west coast, particularly on the Taynish peninsula in Argyll, there remain remnants of the ancient Celtic Rainforest.

Scotland is also famous for its moorlands, or “muirs.” Calluna vulgaris, or heather, is probably the plant most associated with Scotland. Heather and malt have, since at least the Middle Ages, been used as ingredients in gruit, a mixture of flavorings used in the brewing of heather ale. Heather is also used to make honey, for charms, in flower arrangements, to dye wool, to tan leather, and for other uses. Other characteristic flora of the moorlands includes cotton-grass, bracken, crowberry, and sphagnum. The UK’s only arctic tundra is found in the high summits of the Cairngorm Mountains — although it is threatened by global warming. Snow has been known last from one winter to the next on Ben Macdui and long-lasting snow patches support communities of mosses, lichens, and liverworts.

The unicorn became Scotland’s national animal in the 12th century. As a toddler, I remember going somewhere near Lexington, Kentucky where there were lion and unicorn seals, and learning the nursery rhyme, “The Lion and the Unicorn.” Unicorns, of course, are the mortal enemies of Lions and England had adopted the lion as its heraldic animal. Neither mammal ever lived in the British Isles, though, and actual large mammals like beaver, boar, brown bear, elk, lynx, walrus, and wolves, were all long ago hunted to extinction. Bird species including capercaillie, Dalmatian pelican, eagle owl, goshawk, great bustard, night heron, osprey, spoonbill, sturgeon, white stork, and white-tales eagle are all bird species which no longer grace Scotland’s skies.

Admittedly, I didn’t see much at all of the Scottish countryside, arriving as I did by train. However, for all the praise I’ve I’ve heard of it and the British countryside, I was struck by how much it resembled the American Middle West. Switch out a stone wall or hedge for a barbed wire fence and a Gothic church for a Mid-Century Modern one and it could be the countryside outside of DeKalb, albeit apparently as tame as the lawn surrounding a corporate office park.

The threatened Scottish wildcat is the only wild cat species in Great Britain. After them, the most ferocious wild animals are probably foxes or badgers. Other animals not hunted into extinction included the mountain hare, pine marten, red squirrel, and stoat. In recent decades, work has been done to rewild Scotland. The white-tailed sea eagle was reintroduced in the 1970s followed by the red kite in the 1980s. More recently there have been experimental projects, plans, and efforts to reintroduce the beaver, lynx, wild boar, and wolves.

HUMAN DEMOGRAPHICS

As of 2001, the human population of Scotland was 5,062,011. Scotland has three officially recognized languages: English, Scots, and Scottish Gaelic. The ethnic demographics of Scotland were, as recorded in 2011, 96% white (84% Scottish, 8% other British, 2% other white, and 1% Irish), 3% Asian (1% Pakistani, .6% Indian, .6% Chinese, .1% Bangladeshi, and .4% other Asian), .6% African (.4% Arab, .1% Caribbean, and .1% other African), and .3% other ethnic group. Most of Scotland’s people live in the Central Belt, a region which contains the cities of Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Perth. The only major city not located in the Central Belt, in fact, is Aberdeen. Of the more than 790 islands, fewer than 90 are currently inhabited.

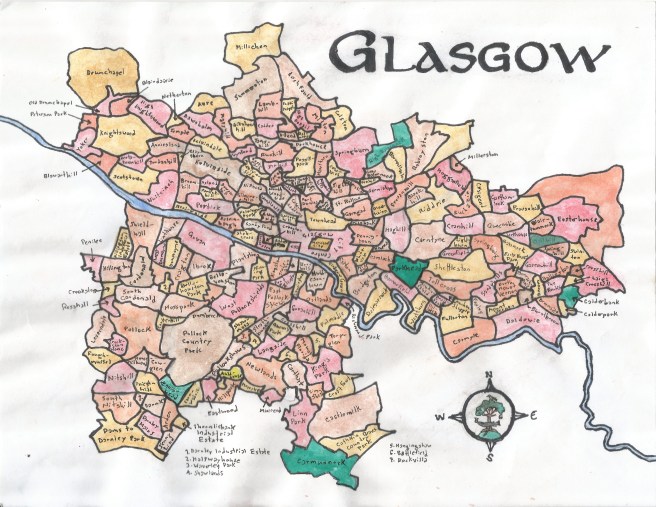

Glasgow, Scotland’s most populous city, had a population of about 584,000 in 2011. Greater Glasgow was then home to about 1.2 million people — or nearly a quarter of all Scots. Glasgow’s population peaked in 1938 when it reached 1,127,825. In part to relieve overcrowding, five “new towns” were created: Cumbernauld, East Kilbride, Glenrothes, Irvine, and Livingston. Large-scale relocations to these towns led to a massive reduction in Glasgow’s population.

ARCHITECTURE OF GLASGOW

Glasgow was founded in the 6th century by a Christian missionary, Saint Mungo, who established a church on the Molendinar Burn (the present-day site of Glasgow Cathedral, dedicated in 1136). Glasgow became a religious center and grew over the centuries that followed. The University of Glasgow was established in 1451. Provand’s Lordship, an historic house-museum, was built in 1471 as part of St Nicholas’s Hospital.

Today, little of Glasgow’s medieval architecture remains and most of the modern city was built in the 19th century. That century produced two of Scotland’s most praised architects, Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) and Alexander Thomson (1817–1875). There are numerous attractions built during the Victorian Era, including the Garnethill Synagogue, the Glasgow City Chambers, the Holmwood House, the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, St. Vincent Street Church, and the main building of the University of Glasgow. The most common sort of building in Glasgow, from what I could tell, were the red and blond sandstone tenements which, I’ve read, were prior to the 1956 passage of the Clean Air Act blackened by soot and pollution. It was in one of these tenements where we lodged for the duration of our short stay.

In the 1960s, many of the old tenements were demolished to make way for the high-rise tower blocks were constructed in Glasgow and peripheral areas like Castlemilk, Drumchapel, Easterhouse, Milton, Nitshill, and Pollok. I happen to like their appearance but having never lived in one, can’t offer comment on what they’re like to actually live in. There’s contemporary architecture too, of course, and in 1999 Glasgow was designated UK City of Architecture and Design. Notable examples of contemporary architecture include the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, the Glasgow Science Centre, the Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre, and the Zaha Hadid-designed Riverside Museum.

TRANSIT IN SCOTLAND & GLASGOW

No piece on travel would be complete without mention of transit. Like anywhere else, there are roads, ship ports, and airports in Scotland, but since there is rail, that’s what we mostly relied upon when not walking.

The train from London to Glasgow takes about four and a half hours to cover a distance of about 620 kilometers and a young woman from London sat next to me and voiced her displeasure with this fact. I told her that a journey of similar distance, from Los Angeles to San Francisco, takes about twelve hours by train, and deposits the rider in Oakland or Emeryville, not San Francisco — because America is No. 1. She expressed surprise. tThankfully, the California High-Speed Rail, currently under construction, will hopefully reduce the travel time to about four hours.

Scotland’s rail network includes about 3,000 kilometers of track and 35 stations. An average of 89.3 million passenger journeys are made by rail annually. Glasgow Central station was opened on 1 August 1879 by the Caledonian Railway. The smaller, older, Glasgow Queen Street railway station was opened on 21 February 1842 by the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway.

Once in Glasgow, we mostly got around on the Glasgow Subway. Having begun operation on 14 December 1896, it is the third oldest underground metro system in the world after the London Underground and Budapesti metró. It runs from 6:30 to 23:40 Monday to Saturday and 10:00 to 18:12 on Sundays. Despite the age of the system, it includes a solitary line, with orange trains circling along a 10.5-kilometer loop, earning it the nickname the “Clockwork Orange.” There are fifteen stations along the subway and they, and adjacent pubs, have become the focus of a pub-crawl inevitably named the Subcrawl.

DRINKING IN SCOTLAND

On rare occasion, stereotypes actually ring true, and it is true that Scots drink a lot of booze. According to statistics analyzed for the Scottish Government in 2009, Scotland had the eighth-highest level of alcohol consumption in the world — kept out of the top spot by Luxembourg, Ireland, Hungary, Moldova, Czech Republic, Croatia, and Germany. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, a higher number per capita of Scots do cocaine regularly than any other nation (the US is No. 2). Whether or not Scots and Americans are stereotyped as cokeheads, I don’t know. None of us did any cocaine, nor did we undertake the Subcrawl, but we did check out a few Glasgow pubs, bars, and a brewery. Our friend Chris, a man about Glasgow, provided us with a fairly thorough guide to the city’s pubs and bars.

In the City Centre he recommended The Pot Still, The Horseshoe Bar, The State Bar, the Bon Accord, and The Scotia Bar. In South Glasgow, he listed The Laurieston Bar, The Allison Arms, and the Queen’s Park Café. In West Glasgow, he suggested The Ben Nevis Bar, The Grove, The Park Bar, The Lismore Bar, The Doublet, and The Arlington Bar. In the East End, he offered no recommendations. Although he assured me that there are “loads of traditional pubs along the Gallowgate,” he also cautioned that I’d probably need to be harder than him to walk into any of them. Another Glaswegian acquaintance, Michael, suggested the Òran Mór. Obviously, we didn’t patronize half of them but we did get around.

Scotland’s best-known alcohol is Scotch whisky (spelled without an “e” in Scotland), known in Scots Gaelic as “uisge-beatha na h-Alba,” or, in American English, usually simply as “scotch.” Scotch is a malt whiskey or grain whiskey made in a specified manner — namely that all Scotch must be aged at least three years in oak barrels and produced in Scotland. Originally all Scotch was made from malted barley but since the 18th century, wheat and rye have also been used. To my mind, it is by far the best whiskey — although I won’t say no to Japanese whiskey, (most) Irish whiskey, or (most) Canadian rye. I will, however, sometimes pass on bourbon, because we have to draw the line somewhere. Other common Scottish alcoholic beverages include Scottish Ales and Drambuie, a liqueur made in Edinburgh. Irn-Bru, a carbonated soft drink, is sometimes referred to as “Scotland’s other national drink.”

CUISINE OF SCOTLAND

Scottish Cuisine shares attributes with English Cuisine but naturally has its own distinctive dishes and practices as well — including a discernible French influence (owing to the “Auld Alliance”). Whereas an English “full breakfast,” might typically include back bacon, eggs, grilled tomato, grilled mushrooms, sausage, baked beans on toast, black pudding, hash browns, and bubble and squeak; A Scottish full breakfast, by contrast, might contain back bacon, eggs, grilled tomato, grilled mushrooms, Lorne sausage, baked beans on toast — and white pudding, fruit pudding, oatcakes, tattie scones, and sometimes the most Scottish of culinary items, haggis.

Scotland’s national dish was possibly introduced by the Norse during their invasions of Scotland. It’s essentially just bits of ground organs and entrails stuffed inside the stomach of either a sheep or pig. Being made nearly entirely of animal parts, you might not expect it to lend itself to vegetarian substitutes and yet, since the 1960s there have been meatless imitations that usually substitute nuts, mushrooms, oats, lentils, beans, &c for offal. Having been a vegetarian for most of my life I’ve never had real haggis — nor have I ever wanted to. In 2011, though, I had a go at making a vegetarian version for a Burns Supper. I followed a recipe, which for me feels a bit like flying blind, but I was assured by several who sampled it that it was good. Perhaps that was mere politeness — or perhaps I’d missed the mark, as I don’t recall anyone ever describing the real thing as being especially tasty.

It might seem like a country with such a national dish wouldn’t be especially receptive to vegetarianism — or even good food — but, as is so often the case, this didn’t prove to be true. In Scotland, meat was historically eaten rarely except by lords and ladies whilst common folk raised gardens, orchards, and used animals for dairy products and eggs. Average Scots ate fish, of course, but the ocean also provided sea oak (aka arame), carrageen moss, dabberlocks, and thongweed. In 2013, PETA named Glasgow the most vegan-friendly city in the UK. One of our meals was at Mono Cafe Bar, a vegan café in a live music venue with good beer and an attached music shop, Monorail, owned by Stephen Pastel.

Of course, there are cuisines available other than Scottish and I don’t think that any of our meals were taken at explicitly Scottish restaurants. The night we arrived in Glasgow, I tried to order a pizza for delivery, only to realize that it was after midnight — a fact which hadn’t dawned on me it was still dusk. I realized then that I’d never before been as far north as the 55th parallel. My last meal before returning to England was at the nominally Mexican Taco Mazama, where I ordered a burrito. The first sign of trouble should’ve been that the employee couldn’t roll the tortilla properly. He apologized and asked me “what part of the island are you from?” Although the restaurant bills itself as “Mexican Street Food,” menu items include vegan mac and cheese and haggis burritos. My burrito was haggis-free… but more resembled (once I assembled it properly) a veggie wrap than a burrito and the rice tasted vaguely South Asian.

We also lunched on one occasion at Hanoi Bike Shop, a Vietnamese restaurant. At the time there was a young Vietnamese woman in the restaurant, politely offering critiques of the probably Google-translated Vietnamese on the menu. When it came time to take our order, the waiter kindly (although unnecessarily) walked us through an explanation of the items. Of course, there’s no way he’d know that we came from the metropolis which is home to more Vietnamese than any city outside of Vietnam. Interestingly, the sriracha was not Huy Fong, the ubiquitous Los Angeles-made brand than may consumers think is the only sriracha, but rather Flying Goose, a brand made in the actual birthplace of the sauce, Thailand. I don’t remember what any of us ate — although I remember it was good and recognizably Vietnamese. I don’t believe that there was bánh mì on the menu though. Although commonly used to refer to a sandwich, bánh mì it actually refers simply to bread (literally “loaf noodle”). I mention this only for the sake of making the following segue somewhat less awkward.

The Scots also have a long tradition of bread making. Since wheat doesn’t do well in damp weather, traditionally Scottish breads were mostly made from oats or barley — which are also used to make porridge and oatcakes. Although more properly characterized as a cake, Scotland is also famous for its delicious shortbreads. The oldest known recipe for shortbread appears in a printed recipe from 1736. Other items and dishes popular in Scotland (both vegetarian and non-vegetarian) include Abernethy biscuits, apple frushie, bannock, bawd bree, Berwick cockles, Bishop Kennedy, black bun, Bonchester cheese, brose, burnt cream, buttery, caboc, clapshot, clootie, cock-a-leekie soup, cranachan, crowdie, curly kail, deep-fried Mars bar, drop-scones, Dundee marmalade, Dundee cake, Dunlop cheese, Edinburgh rock, Empire biscuit, fatty cutties, festy cock, flee cemetery, gigha, granny sookers, hairst bree, hatted kit, hawick balls, jethart snails, Lanark blue, lucky tatties, marmalade pudding, Moffat toffee, neeps and tatties, pan drops, pan loaf, partan bree, plain breid, puff candy, rowan jelly, rumbledethumps, Scotch broth, Scots crumpets, Selkirk bannock, skirlie, slaes, soor plooms, sowans, stapag, strippit baws, tablet, tayberries, Teviotdale cheese, tipsy laird, and Yetholm bannock.

SCOTTISH LITERATURE

The history of Scottish literature dates back to at least the 6th century CE when works written in Brythonic appeared. Later works were composed in Latin, Gaelic, Old English, and French. The oldest surviving text in Early Scots is Brus, an epic poem written in the 14th Century by John Barbour (no relation to J. Barbor & Sons — although note to self: have the waxed Una purchased but then put through the laundry repaired). The country’s most emblematic writers are probably the poet Robert Burns and the novelist, Sir Walter Scott. I first read Burns’s poetry when I was sixteen and found it so moving that I set about memorizing several of his works (and those of John Keats). Today, Burns supper — a celebration of his life and poetry observed on 25 January — is more widely celebrated than Scotland’s national day, Saint Andrew’s Day (30 November).

Sir Walter Scott is best known for his Waverly books and the novel, Ivanhoe. My mother read Ivanhoe to me when I was a child, although I remember nothing about it except the cover of our edition. However, perhaps it counts for something that I live in an area of Silver Lake that was developed as the Ivanhoe Tract, on Rowena Avenue, named like many streets in the area for a character in that work. Other famous Scottish authors of the 19th century include Arthur Conan Doyle, George MacDonald, J. M. Barrie, and Robert Louis Stevenson. In 1993, Scottish writer Irvine Welsh published his first novel, Trainspotting, which was adapted into the hit film in 1996.

FILM OF SCOTLAND

Although Trainspotting was directed by an Englishman, it starred a mostly-Scottish cast and although set in Edinburgh, was filmed almost entirely in Glasgow. Scotland and Glasgow have produced many films, filmmakers, and actors. One of the most prolific was Glaswegian Frank William George Lloyd, who directed 135 films — and like so many of his countrymen retired to Santa Monica. In preparation for visiting Glasgow, Una and I watched Gregory’s Girl, a 1981 film made by Glaswegian director Bill Forsyth.

In the year before Trainspotting was released, there were two big Hollywood-Scottish co-productions which were commercially successful, if not especially good — Rob Roy (directed by Scottish director, Michael Caton-Jones, but starring Irishman Liam Neeson and a cast rounded out by Americans) and Braveheart. The latter, directed by Mel Gibson, won a Best Picture Oscar and later topped a poll conducted by Empire of the “The Top 10 Worst Pictures to Win Best Picture Oscar.”

Shortly after the release of Trainspotting I remember seeing Gillies MacKinnon’s Small Faces in the theater, which I can’t remember very well but think that I liked. I loved, on the other hand, Sweet Sixteen, which I watched a few times. Like Trainspotting it was directed by an Englishman, and like that film starred a Scottish cast and was written by a Scotsman, in this case, Paul Laverty. It’s filmed in and set around Greenock, Port Glasgow and I highly recommend it (and all Ken Loach films, really) to anyone who hasn’t seen it. Sweet Sixteen was filmed in Scots English and without subtitles, I imagine I’d’ve been utterly lost. There are Scots language films too, which I’d like to check out, including Neds and Ratcatcher, as well as films in Scots Gaelic such as Being Human, Foighidinn – The Crimson Snowdrop, The Eagle, I Know Where I’m Going!, King Arthur, and Seachd: The Inaccessible Pinnacle.

MUSIC OF SCOTLAND

For many, the words “Music of Scotland” immediately call to mind the Great Highland Bagpipe, and probably little if anything besides. Since bagpipes are known throughout Europe and much of North Africa, Turkey, Caucasia, and the Persian Gulf, I asked a bagpiper friend why in America, at least, we only think of the Scottish ones… and usually imagine playing “Amazing Grace” at a police funeral. He and others have theories — which are interesting but take too long to explain so I’ll leave it to the reader to research if interested. Of course, bagpipes also aren’t the only instrument employed in the performance of traditional Scottish music — others include the accordion, clàrsach (harp), fiddle, and penny whistle.

Although English pop music has been popular in the US since at least the British Invasion, Scottish music has generally been more marginalized or had its Scottishness downplayed. The famed British Invasion, really, was an English Invasion, as it involved no Welsh, Northern Irish, or Scottish bands. Scottish band the Poets, though good and additionally managed by Andrew Loog Oldham, made absolutely zero impact in the US. Two Scottish singers who did have some success in America, Donovan and Lulu, weren’t really part of that movement.

Donovan’s big American hits were “Sunshine Superman” and “Mellow Yellow,” pop gems released in the psychedelic year of 1966. His previous releases had been hits in the UK, where he was closely associated with the British Folk Revival. He was “folk” in the sense that he played acoustic guitars and wore, like Dylan, a Greek fisherman’s cap and probably corduroy. He was not so much folk in the more meaningful sense of one who performs songs written centuries ago in ages past and transmitted orally. I’m not opposed to singer-songwriters, mind you, it’s just that to my mind, a 1,000-year-old composition performed on a theremin by someone wearing Comme des Garçons is more folk than anything included on Spotify’s playlist of “blissed-out, repeat-free hours of new releases and cherished faves” performed by millennials in Coachella Festival line .

In other words, I’m not a folk purist like Ewan MacColl, who famously barred many talented musicians from performing in his folk club for the crime of playing originals. Furthermore, many of those associated with the folk revival performed both traditional and original material. Some of my favorites include Scottish troubadours Bert Jansch, The Incredible String Band, Alex Campbell, Hamish Imlach, Isla Cameron, and Shelagh McDonald. None were ever popular in the US, though, and as far as I know, there was little if any acknowledgment that the likes of Al Stewart, Average White Band, Gerry Rafferty and Stealers Wheel, Nazareth, Pilot, or Mark Knopfler of Dire Straits were Scottish.

Two exceptions were The Bay City Rollers and AC/DC. The Scottishness of Bay City Rollers was part of the marketing. They wore (hideous) plaid outfits and were billed as the “tartan teen sensations from Edinburgh.” Ironically, the band had chosen their name in an attempt to sound more American, naming themselves randomly after Bay City, Michigan. AC/DC, though formed in Australia, are led by Glasgow born Angus Young. The ban’ds most celebrated singer, Bon Scott, was born in Forfar. As if that weren’t enough, they stuck screaming bagpipes front and center on the 1975 classic rock staple, “It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock ‘n’ Roll).” I think many people think that Scottish band Big Country used bagpipes on their only American hit, “In a Big Country,” but it was actually a guitar performed to evoke a bagpipe. Although that was a nod to their Scottish origins, the so-called Second British Invasion (Culture Club, Duran Duran, Eddy Grant, The Fixx, A Flock of Seagulls, Howard Jones, the Police, Kajagoogoo, Madness, Thomas Dolby) was mostly Scott-free, with mainstream Scottish hitmakers like Sheena Easton and Simple Minds not really lumped in with that movement.

I’m not really a fan of most of those bands, though, so I’m getting away from myself, perhaps. I suppose I’m trying to segue into my view of Scottish indie bands of the 1980s. Although I was a bit young and then just transitioning into indiedom, I had an idea at the time that Scotland was a bit like New Zealand — a place ignored by Anglophiles for the reason that it wasn’t England, and yet a place which seemed to produce more than its fair share of highly appealing indie pop. The main Scottish band to get play on college radio, at least in central Missouri, were the Cocteau Twins and the Jesus & Mary Chain.

The Cocteau Twins came from Grangemouth, near Edinburgh, which was also home to the Fire Engines, Joseph K, one album wonders The Shop Assistants, and underrated Scottish baggies, The Wendys. However, to extend the New Zealand analogy, if Edinburgh was Wellington (or perhaps Aukland), then Glasgow was Scotland’s Dunedin. How could a city of a million residents produce so many excellent bands — including Aztec Camera, The Bluebells, BMX Bandits, the aforementioned Jesus and Mary Chain, Lloyd Cole and the Commotions, The Mackenzies, Meat Whiplash, Orange Juice, The Pastels, Primal Scream, The Soup Dragons, Strawberry Switchblade, Teenage Fanclub, The Vaselines, and The Wake.

In the early ’90s, there was an onslaught of American grunge and heavy metal on the British charts. The British music press — who’d largely been dismissive of Scottish indie in the 1980s for not being innovative or forward-looking like acid house or hip-hop — championed a crop of similarly-minded English bands under the banner of Britpop. Conspicuously absent from the movement were any Scottish bands, other than Travis or maybe, the Beta Band. Britpop wasn’t built to last and by 1997, the writing was on the wall. No matter how fruitless, the music press turned to promoting Welsh landfill indie rather than pay attention to the music of Scotland.

Around the same time, the newly formed Scottish band, Belle & Sebastian began quietly releasing music, and although Scottish, the Anglophiles that I knew embraced them as a kind of “New Smiths” (despite their sounding nothing like the Smiths). As their popularity grew, the swell seemed to lift other Glaswegians like Arab Strap, Camera Obscura, and Mogwai. In 2001, an actual Glaswegian indie supergroup, the Reindeer Section, formed. I never heard an Anglophile or anyone else suggest that there was a “Cool Caledonia” movement or identify as an Albaphile, but around the same time the nightclub scene began to be populated with tiny marinière and sunglasses-wearing Bobbie Gillespie clones. Even more disturbingly, “twee” had at some point apparently been appropriated as a self-descriptor. A few years later, to my continued surprise, an acquaintance whom I’d not seen for some time encouraged me to see his band, The Tartans. Two years ago I even saw an American band called Loch Lommond open for the Vaselines… although the latters’ Frances McKee mocked the way that they pronounced their own band name. I suppose that that’s as a good a place as any to end this rumination, as I hate to write conclusions. I’ll just end by offering this, ‘Tis a doolally warld!

Lots of good quality content in this post! 🙂

LikeLike