INTRODUCTION

Los Angeles was founded on this day, 18 February, in 1850. A majority of insufferable pedants will have just jumped to the comments to let me know how wrong I am and that “Los Angleles” refers not the Los Angeles County but only to the City of Los Angeles. The rest of us, I think, use “Los Angeles” inflexibly and, besides, there was a Los Angeles County before there was a City – if we’re being nitpicky. Oh, but can we all agree that Los Angeles County’s flag is one of worst on account of the horrid bar of text at the bottom?

❦

COUNTY BEFORE CITY – AND METROPOLIS BEFORE ALL

If you don’t believe me, engage in this thought exercise. Imagine, if you will, the montage at the beginning of a Hollywood production that’s meant to establish Los Angeles as the setting. The viewer might expect to be subjected to images of a glamorous woman in a big hat and sunglasses emerging from a Rolls Royce on Rodeo Drive, an Angelyne billboard lording over traffic on the Sunset Strip, waves crashing beneath homes on PCH at Point Dume, and some rollerbladers swaying in front of a pier with the sun setting behind it. Perhaps my choice of tropes is too rooted in the 1980s brain candy I routinely ingest via Kanopy but my point is that none of those shots would’ve been filmed in the city of Los Angeles – and yet even the dimmest bulb would recognize their intended meaning.

If you require another example – one loosely rooted in my actual experience – imagine you were moving from an apartment on the west side of Clybourne Avenue, in North Hollywood, to one across the street, in Burbank. Would you tell your friends, before your big move, that you were “leaving town?” This is a trick question – because if you answer “yes,” you can’t also have friends.

For more reasonable people, in other words, “Los Angeles” refers not strictly to the City of Los Angeles. Nor does it necessarily, however, refer strictly to the county. To me, and probably you, it’s Metro Los Angeles – or Greater Los Angeles. In some metropolises, “greater” is more common – e.g. Greater London or Greater Toronto. In others, like Metro Manila or Metro Taipei, “metro” is the standard. I guess some people go for the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area, like they do in New York and Tokyo — but that sounds a bit rigid in the Capital of Casual. Besides, why should Los Angeles commit to one or any?

When I was in college in Iowa, I had a friend and roommate from Chino. Since (before The OC, at least) no one outside of Southern California had ever heard of Chino, he told people in Iowa that he was from Los Angeles. He wasn’t being dishonest or pretentious – in that particular instance – it was shorthand. For all intents and purposes, he was (and is) from Los Angeles. When he moved to Silver Lake after college – a neighborhood I’d never before then heard of – I became an Angeleno but he already was one. It’s not as if there is even a term for a person from Chino. “Chinese” is already spoken for. If you’re tempted to coin one, don’t forget about people from Chino Hills.

Another of our friends was from Pomona. And one of their friends was from Upland, I think, or maybe Ontario. She told people that she was from Claremont… but that fib only meant something within their circle of Pomona Valleyites. Most Anglelenos don’t know which Pomona Valley communities are in which county so, it should come as no surprise that to most of the world, Claremont might as well be Montclair… and Ontario is in another country. To me, who’d never heard of any of those places, they were just Anglenos. They, on the other hand, knew who Huell Howser was, had opinions about In-N-Out, and could sing the lyrics to more than one Oingo Boingo song. What else could they be?

❦

SUBURBS IN SEARCH OF A METROPOLIS IN SEARCH OF SUBURBIA

One of the things I’ve been thinking about lately is that old phrase: Los Angeles is (fill in the blank with a number) suburbs in search of a metropolis. People repeat it still because they wrongly assume that it makes them sound “in the know.” It’s actually minorly annoying, like needlessly italicizing universally recognized Spanish words, making that “LA” handsign, or “correcting” people’s pronunciation of Los Feliz or San Pedro lest they inadvertently reveal, in their pronunciation, that they’re not from here. Why would anyone care if someone knew that they weren’t from a place — other than a superspy? Most of us choose where we live but not of us chose where we’re from.

Whilst I do wonder when people decided that the “correct” pronunciation of centuries-old Spanish ranchos was in a monolingual Anglo accent, more interesting to me, for the time being, is getting to the bottom of the “six suburbs in search of a metropolis” quote. Nowadays, it seems, it’s most often attributed to Aldous Huxley, who supposedly wrote it in his 1925 book, Americana, a work that, somewhat problematically, never existed. At some point in the mid-1980s, around the time the number of suburbs in search of a metropolis grew to 100, it started to become widely attributed to H.L. Mencken. That sounded believable because few people have any idea who he is and even fewer have read anything that he wrote. The quote, according to some sources, appeared in the April 1927 edition of Photoplay. I’ve read it. It didn’t.

Before that, the quote was variously attributed to a wider variety of writers, including Algonquin Round Table member, Alexander Woollcott. Woollcott is less famous than another member of that circle, Dorothy Parker, which is presumably why the quote became widely attributed to her despite no written record ever suggesting that. The quote was attributed, in 1939, to Robert Harari, who listed the number of suburbs as six. Harari was a film and later television writer, so it’s conceivable that he said it at some point, or at least repeated it. The most likely source of the quote, from what I can tell, was actually playwright James “Jimmy” Gleason, who was quoted as having said it in 1930. Having grown up in New York City – and previously lived in the more traditionally urban Oakland, Portland, and London – he got his first taste of Los Angeles in 1922, when he came to Hollywood to appear as an actor in the film, Polly of the Follies. When he quipped that Los Angeles was “six suburbs in search of a city,” he was likely making a play on the title of the play, Six Characters in Search of an Author (Sei personaggi in cerca d’autore), an absurdist work by Luigi Pirandello. He probably didn’t have six particular examples in mind..

Whoever first made the quip, the meaning was clear — that Los Angeles was a podunk nowhere place with mere aspirations to cityhood but, in reality, just a collection of unremarkable suburbs, none of which individually or collectively amounted to more than just a city-sized population. It appeared in print most often in the 1950s when, thanks to destructive freeways, the decommissioning of urban rail, white flight, “slum clearance,” and “urban renewal,” Los Angeles actually had undone what of what had made it, in the first half of the 20th century, most conventionally urban. The number of suburbs, meanwhile, had grown from six to as many as forty — but most often, for whatever reason, nineteen. In the 1950s, it was written less often by East Coast haters than Angelenos with a sense of shame and inadequacy. It was as if a city had reverted to suburbia — even as it became the most populous county in the nation.

❦

LOS ANGELES – CITY OF REFUGE… FROM CITIES

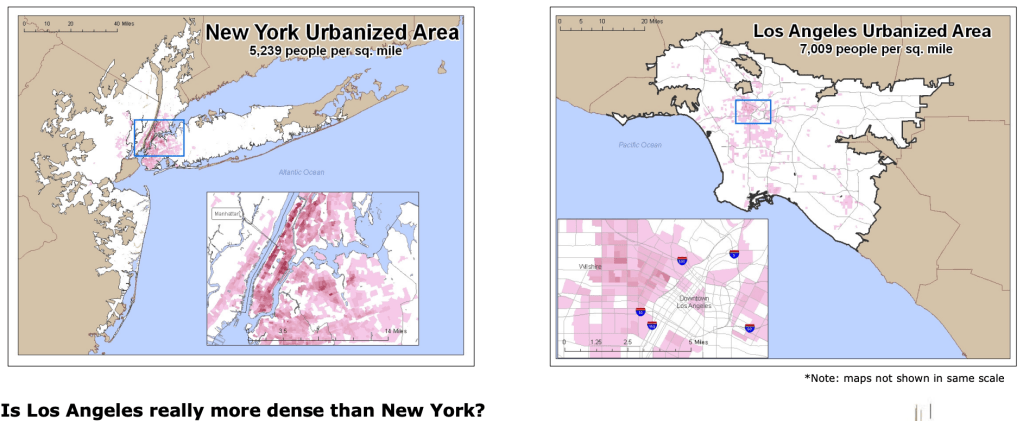

I have met people who (or whose parents) moved to Los Angeles from cities including New York, London, and Taipei – because they wanted to escape all of the conveniences of modern city life and live out some mid-1940s fantasy version of Southern California. In doing so, they have unwisely, and to the detriment of us city lovers, chosen to take refuge in a Metropolitan area home that is home to 18.5 million people. They are seeking breathing room inside the metropolitan area that, since 1985, has been the nation’s most densely populated. They’re hoping to find small town vibes in the city that, since 1984, has been the nation’s second-most populous. There are 3,143 counties (and county-equivalent administrative units) in the US and, since 1954, 3,141 of them have been less populous than Los Angeles County.

Somehow, many of them manage to keep reality at bay. I can’t possibly count how many sleb transplants I’ve heard on podcasts discussing, with apparent glee, their complete and total dependence on their car to get them anywhere and everywhere beyond their front door. They’ll often reminisce about how nice it was to run into friends on the sidewalks of New York but complain about how impossible that is in Los Angeles – where they’ve, inevitably, chosen to live in the Los Angeles equivalent of Broad Channel, Queens instead of somewhere were people walk, like Koreatown, Westlake, or Downtown. You just know that they had committed to car-dependency before ever setting foot on the tarmac at LAX.

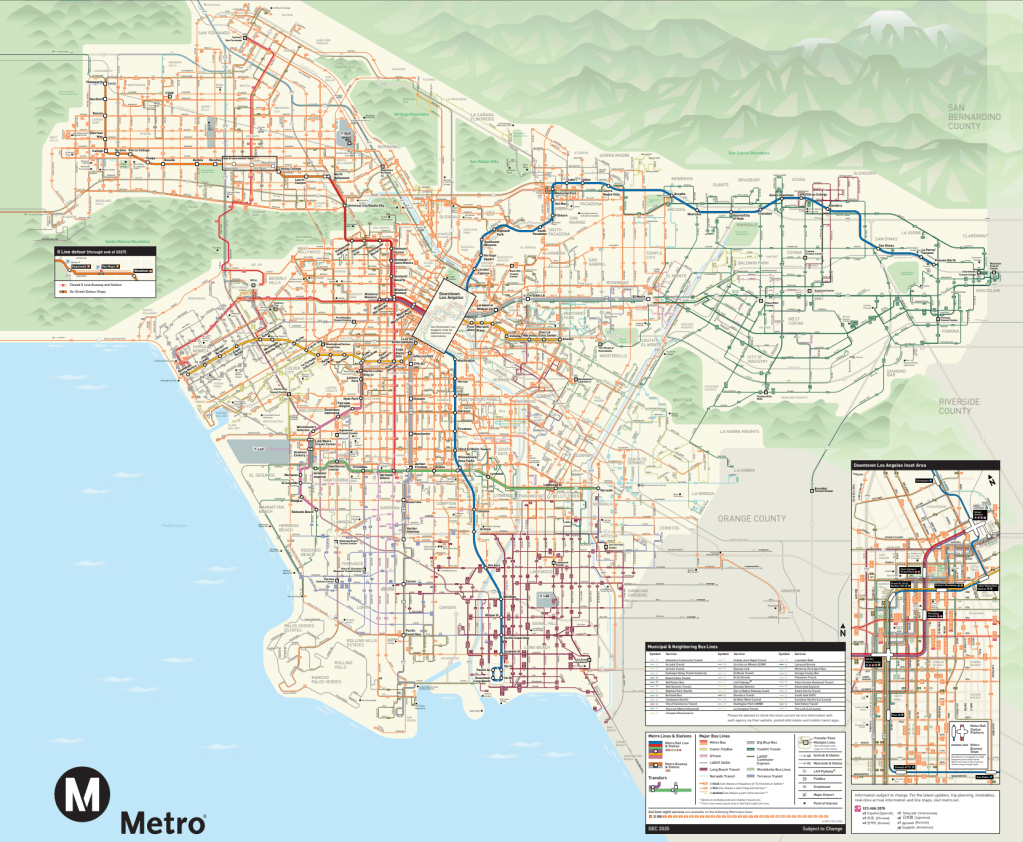

With these people, if you try to point out to them that there’s a bus heading from where they are to where they want to go, that it is arriving in three minutes, that it will take four minutes to get to their destination, and that it will only cost $1.75; they’ll cut you oof before you can finish to assure you that, no – “only way is car. No car no make sense.” They will then stuff themselves into their emotional support SUV, drive it two blocks, spend fifteen minutes looking for parking, and ultimately find it two blocks away. And they will complain for twenty minutes that there aren’t enough places for people to store their cumbersome cars because there are too many cars. For chrissakes, won’t somebody please think of the cars?!

❦

CHUMASH VILLAGE ERA

Long before the urbanization of Southern California, the ancestors of the Chumash settled what is now Metro Los Angeles at least 13,000 years ago. They presumably arrived car-free and managed to thrive here, for over ten millennia, without them. They created roads, like the one that thousands of years later became the city’s main street, Wilshire Boulevard – in order to retrieve oil with which to waterproof their boats, not service their autos.

The Chumash also established villages – not just along the Central Coast – but all the way from Morro Bay to Bolsa Chica and across the Channel Islands. By roughly 9000 BCE, they’d established villages in what’s now Los Angeles, including Hu’wam, Humaliwo, Kaštiq,Kats’ikinhin,Lisiqishi, Lohostohni, S’ap tuhuy, and Ta’lopop. Their villages were, for the most part, essentially permanent, with temporary camps erected to gather resources for them.

Traditional Chumash villages were also highly structured and stratified communities. They included dome-shaped houses called ‘aps, ceremonial dance grounds, semi-subterranean sweat lodges, and storehouses for communal food supplies, usually located near the chief’s residence. The largest was in the Ballona Wetlands, near present day Marina del Rey. Even the Chumash’s largest villages were relatively small, though, and that one was believed to be home to roughly 125 inhabitants at its peak (around 6000 BCE).

TONGVA VILLAGE ERA

The Tongva and their Takic language-speaking brethren arrived in what’s now the Los Angeles area from the Sonoran Desert around 1500 BCE. By then, the Chumash had abandoned many of their mainland villages after a centuries-long megadrought. The Tongva took over some Chumash villages like Topaa’nga – “‘nga” is a Tongva prefix for “place of” and Topaa is a Chumash name.

The Tongva established new villages along inland waterways. Their villages, in some cases, were semi-nomadic because environmental conditions inland from the coast were more prone to change. Major rivers, for example, radically re-routed from time to time. Many of the names of Tongva villages live on in modern Los Angeles place names – even if those places are inevitably less-villagey today: Asuksagna (Azusa), Kawénga (Cahuenga), Kukamogna (Rancho Cucamonga), and Tuxuunga (Tujunga). The Tongva were less strictly hierarchical than the Chumash – a trait common to people whose cultures developed in less resource-rich environments. Their villages reflected this comparative egalitarianism. They were organized in concentric circles oriented round shared open spaces often anchored by a natural feature like a sacred tree. Radiating outward from the center were rings of kiiys (homes made of willow and tule), communal cooking spaces, specialized tool manufacturing spaces, and constructed shaded areas that the Spanish called “ramadas.”

❦

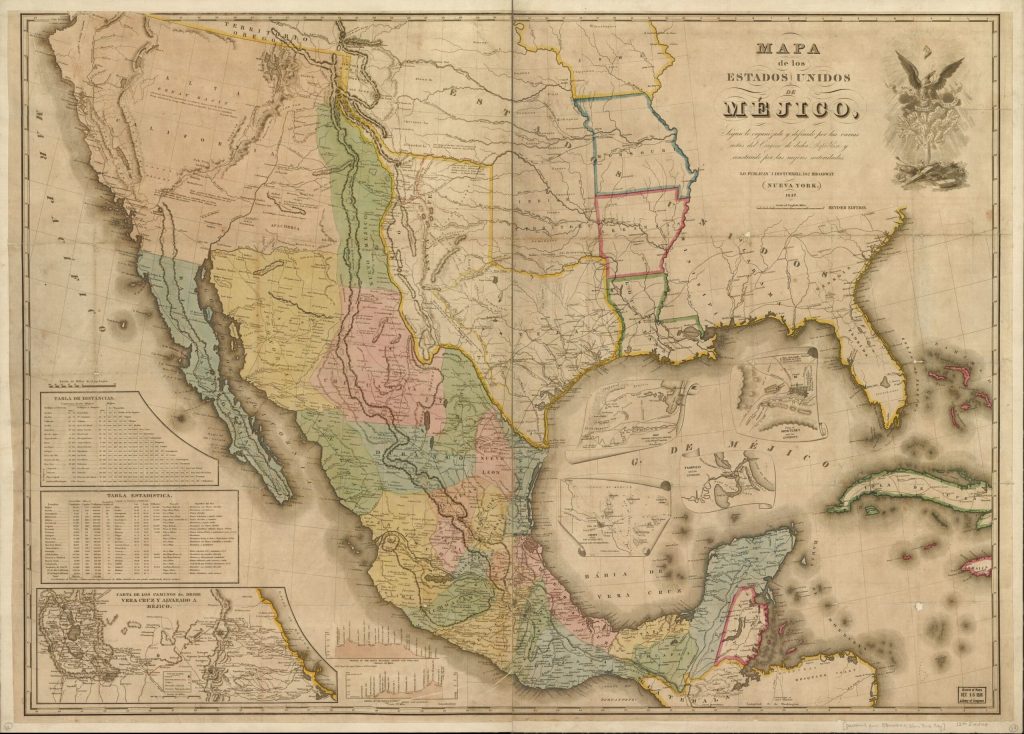

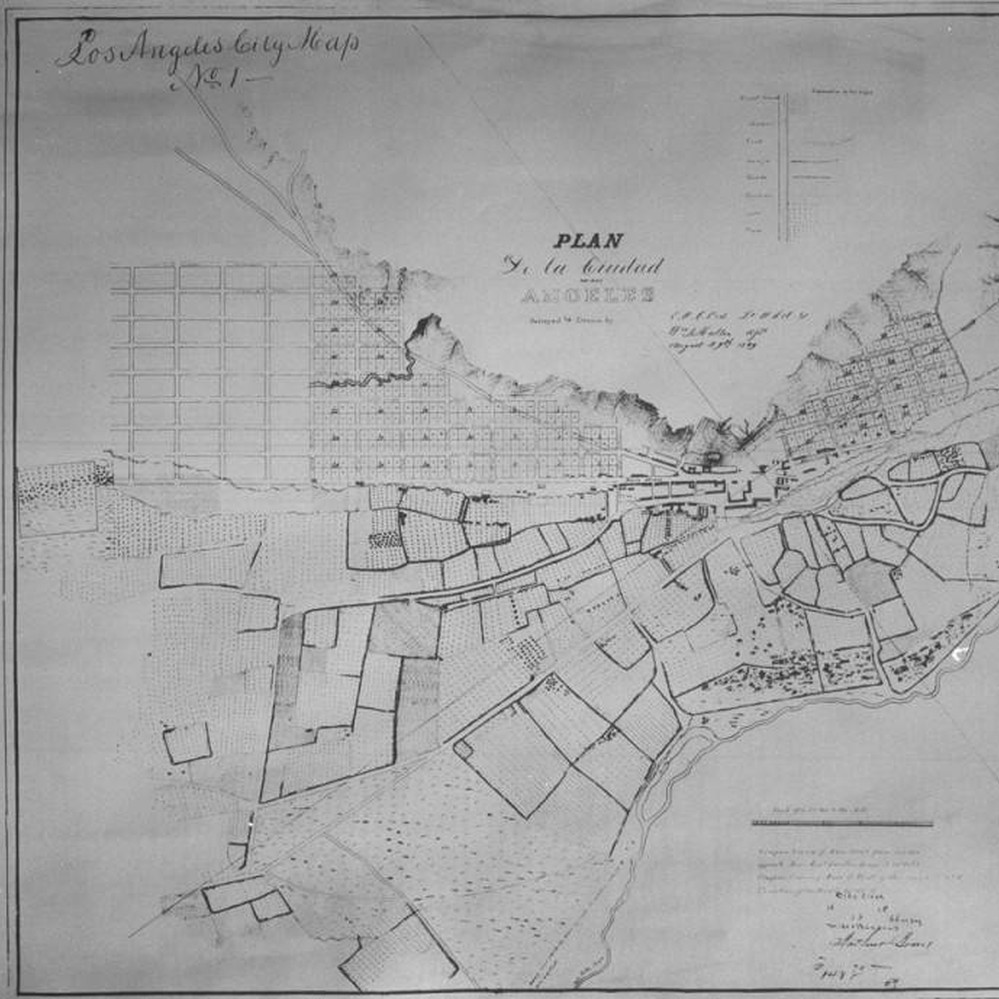

SPANISH VILLAGE ERA

When the Spanish arrived in 1542 CE, they claimed everything they saw for their empire. They didn’t get serious, though, until they built their first of 21 missions in Alta California in 1769. Between 1769 and 1782, they built four military presidios to protect them –San Diego, Monterey, San Francisco, and Santa Barbara. Those all grew, eventually, into cities and towns but the Spanish were less interested in building villages from the ground up than their indigenous predecessors. Across all of Alta California, in fact, they only established three: San José de Guadalupe (1771), Villa de Branciforte (1797), and last of all, El pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles [del Río de Porciúncula?],” or “ L.A.” if you’re into the whole brevity thing, in 1781,They chose the location for Los Angeles based on the existing location of the largest Tongva village, Yaangna. That site, being where it was, offered protection from pirate attacks, a supply of fresh water from the Los Angeles River, and a large population of forced labor – the Yaangnavit.

❦

LOS ANGELES COUNTY IS BORN

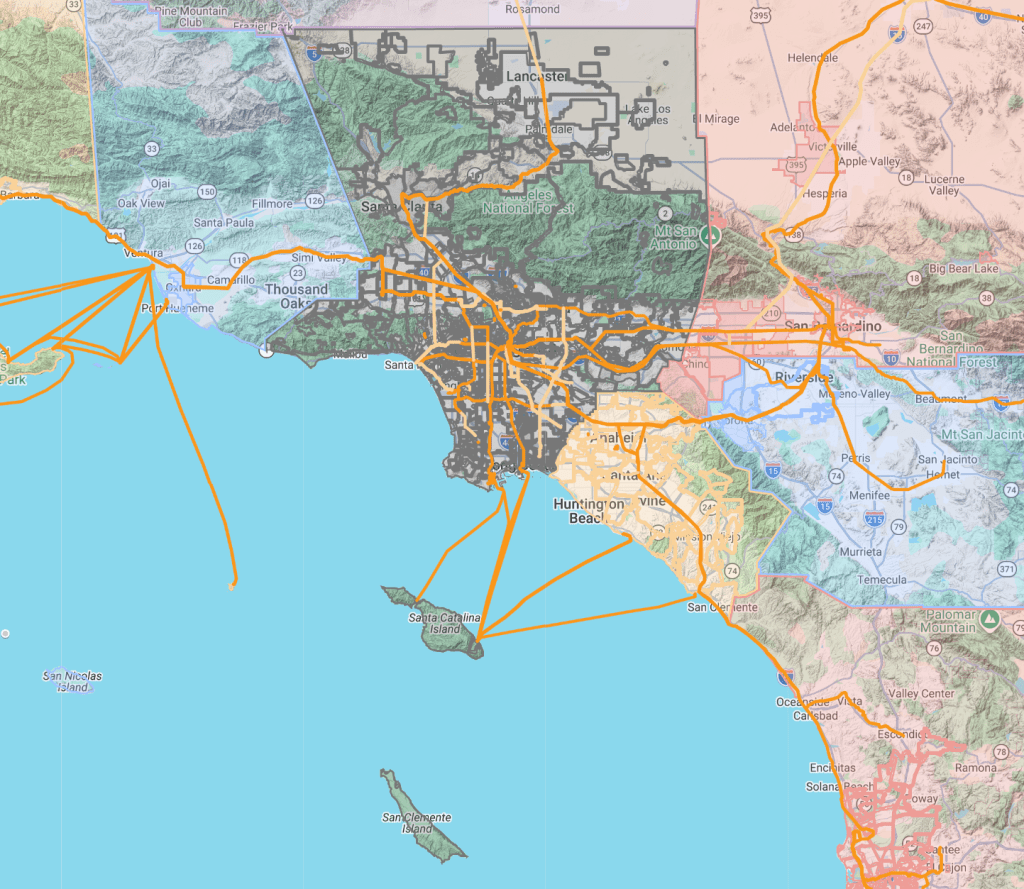

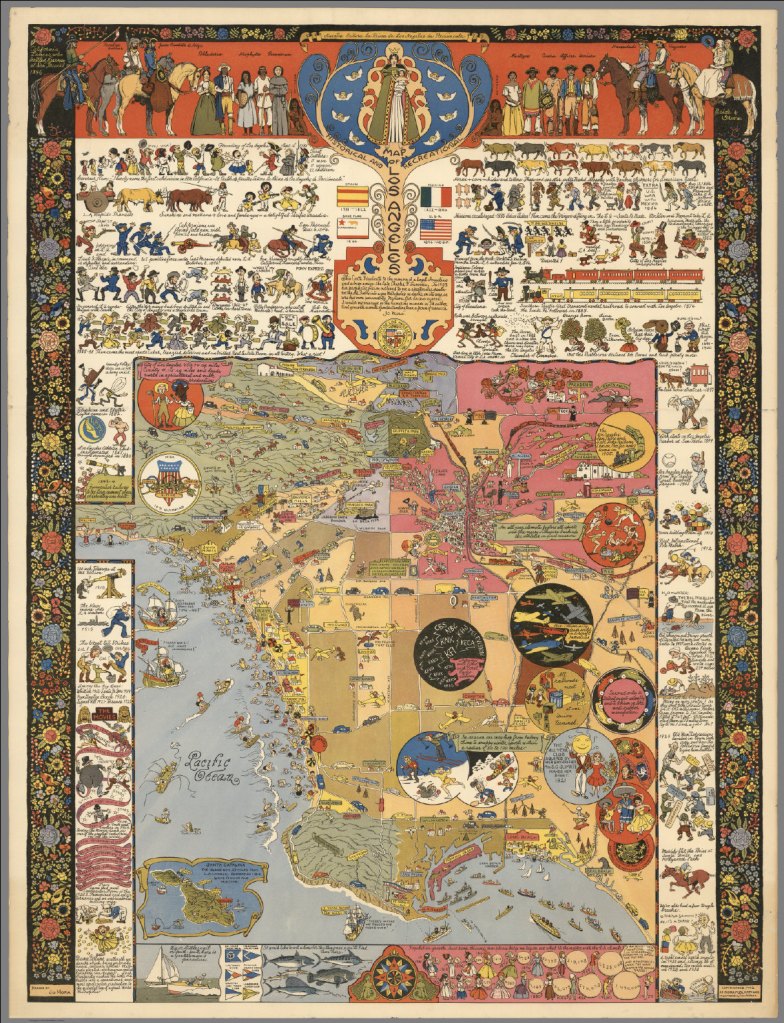

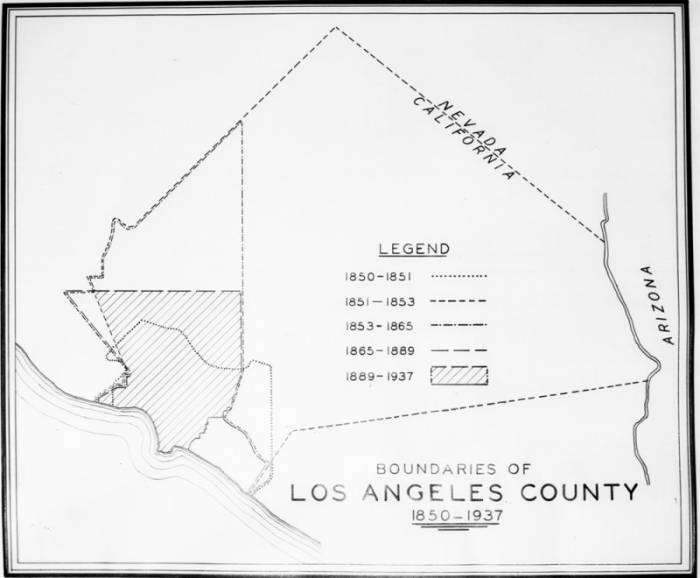

When Los Angeles County was created, it was vastly larger than it is today – and it’s still large. 4,752 square miles (12,308 square kilometers) – a bit smaller than the Bahamas and a bit larger than Qatar… or about the same size as Connecticut. When created, it was 34,520 square miles (roughly 89,000 square kilometers) in size – a bit larger than Austria and roughly the size of the entire state of Indiana.

Los Angeles County spun off new counties, though, birthing parts or all of San Bernardino (1853), Kern (1866), Ventura (1873), and Orange counties (1889) – the last major* succession. The Orange County split resulted in so much bitterness that an appropriately pithy “Orange Curtain” was erected (at least, rhetorically) around 1953. Personally, I’ve always found the divide between North and South County to be more pronounced than, say, the imagined orange divide between La Habra (in Orange County) and La Habra Heights (in Los Angeles County) – but perhaps that’s just me.

*For the pedants still with us: yes, a small section of Los Angeles joined Kern in 2001 for fairly sound reasons, but when some “turncoats” in nearby Gorman tried the same in 2005, all were rightfully hanged as traitors.

❦

VILLAGES AMIDST THE SPRAWL

Los Angeles became a county 45 days before it became a city. The City of Los Angeles was incorporated on 4 April 1850. That made it a city, at least technically. Its population, though, was just 1,610 – which means it was still smaller than that of the town where I finished high school, Pleasantville, Iowa. I never thought of Pleasantville as a “city,” perhaps because the entire “city” had fewer inhabitants than there were students at my previous high school in Tampa. Pleasantville even has more Facebook fans than residents. Nor, though, did I ever think of Pleasantville as a “village,” because, I suppose, that designation sounds a bit twee when applied to a Midwestern farm town – even if my favorite place there, the Dairy Shoppe, clearly wasn’t afraid of a little Middle English affectation. Angelenos have fewer reservations about calling places “villages,” though.

❦

THE BOOM OF THE ‘80S AND THE BIRTH OF A CITY

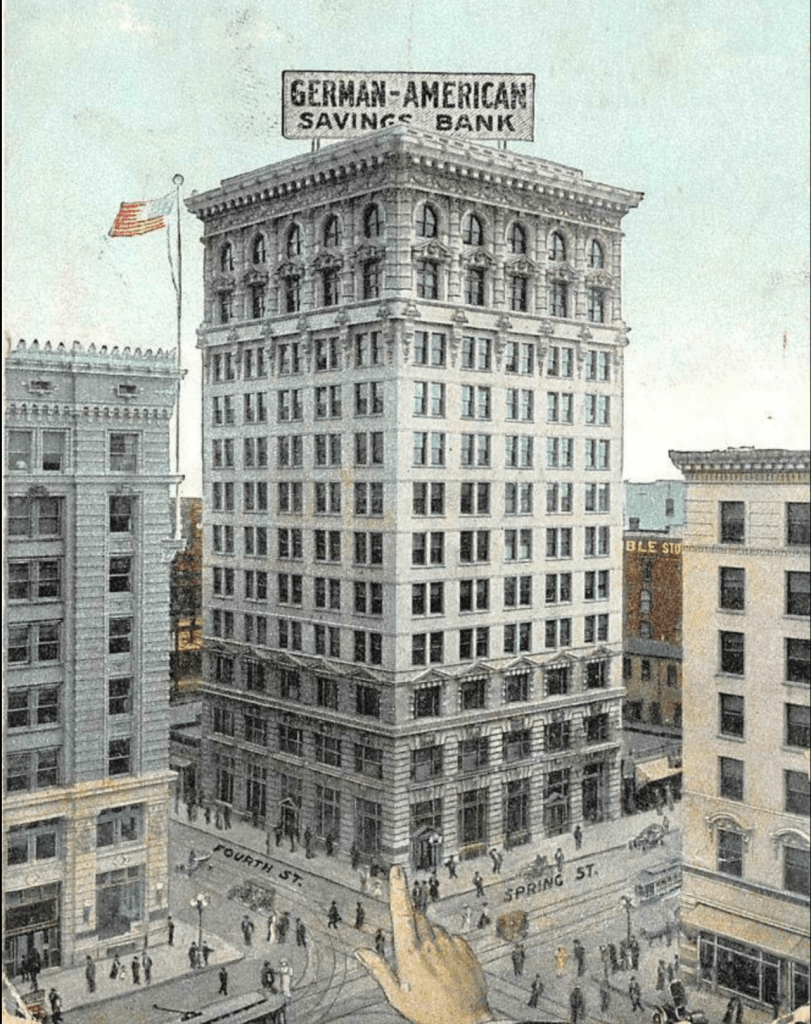

Los Angeles’s first real estate boom exploded in 1887, the so-called “boom of the ‘80s.” Angelenos, then, were seemingly all eager to grow their city. Los Angeles’s population reached 50,000 (the UN and World Bank’s definition) around 1890, which some would count as a “small city.” As it grew, it absorbed smaller communities like Highland Park (1895), Sycamore Grove (1895), and Garvanza (1899). Los Angeles may’ve technically become a city in 1850 – but it only began to even approach “urban” status around the turn of the 20th century. It’s hard for me to imagine anyone describing any place without a single modest skyscraper as “urban.” Los Angeles’s first skyscraper, the Braly Block, was completed in 1903. Urbanity ensued.

Just as there’s no set definition of a city, nor is there a concrete definition of a suburb. The term, from the Latin suburbium, entered the English language around 1350 to describe a place “under” or near an urban place – urban coming from the Latin, urbānus, meaning “pertaining to a city or city life.” But I also wonder if having suburbs makes a place more of a city. It’s hard to imagine a village with suburbs… or even neighborhoods.

In its early years, Los Angeles had a few neighborhoods and suburbs, such as Dogtown and East Los Angeles (as Lincoln Heights was originally known). Some, like Bunker Hill and Crown Hill were, in terms of topography, sur-urban – but sub-urban in terms of population density and development.Many sprang up along streetcar lines – which, incidentally, were often owned by the same man developing the suburbs – Henry Huntington. Streetcar suburbs like Angeleno Heights, Atwater, Echo Park, and Silver Lake are still dominated by leafy streets, one-and-two story buildings, and surface parking lots would qualify them all as “sub-urban” for anyone but the most hysterical city-phobe.

Perhaps one of the true measures of a city is that it absorbsother cities into it. In its early years, Los Angeles swallowed the incorporated municipalities of San Pedro (1909), Wilmington (1909), Hollywood (1910), Sawtelle (1922), Hyde Park (1922), Eagle Rock (1923), Venice (1925), Watts (1926), Barnes City (1927), and Tujunga (1932). Even a century after annexation, many residents of those towns insist on referring to them as cities… well, not so much Barnes City.

Los Angeles experienced its second major population boom in the 1920s, fuelled largely by internal migrants (or “transplants”). In the 1920s, Los Angeles gave birth to the first dedicated sound cinema, the modern supermarket, produced 90% of the world’s films, and was the leading oil producer in the world. It had surpassed San Francisco in size (something which ignited a bitter, inextinguishable, and completely one-sided rivalry) and had the largest electric interurban rail network in the world.

Ironically, it was also in the 1920s that seeds of its quest for village-life began. Perhaps it’s because Los Angeles was marketed to transplants as something it was not. It was promoted to whites from the Midwest, East, and South as “the White Spot of America.” Meanwhile, the Mexican population tripled. The Second Great Migration saw the black population of Los Angeles increase 125%. The anti-union capitalists, seeking cheaper labor, lured workers from Asia in large numbers and, by the 1920s, Los Angeles was home to the largest population of Japanese outside of Japan. But that diversity was often hidden in plain sight. Racist housing covenants and sundown towns were used to exclude non-white, non-Protestants across most of the region. White transplants, meanwhile, celebrated their homelands at frequent and massive state society picnics held throughout the region. Long Beach came to be widely known as “Iowa By the Sea” even though, today, it’s more well-known for having the largest Cambodian population outside of Cambodia.

❦

PLANNED VILLAGES

The 1920s also gave us the planned (and then exclusively white) villages of Westwood Village and Leimert Park Village. The ’30s brought Lakewood Village, Studio Village, Valley Village, and Westside Village. Villages, it would seem, were always white coded. Non-whites and “not-quite whites” formed village-like enclaves like Chinatown, Frenchtown, Greektown, Little Italy, Little Manila, and Little Tokyo. That changed in 1939, when a black attorney from Chicago, Melvin Ray Grubbs, created Sun Village, and targeted it specifically as a haven for black families who were being systematically excluded from homeownership almost everywhere else. More nominal villages followed in the 1940s, including Hillside, Mayflower, Southwest villages.

❦

THE VILLAGE-IFICATION OF LOS ANGELES

Eventually, existing neighborhoods – especially commercial districts – would be re-branded as villages: Fairfax Village, Atwater Village, Larchmont Village, and Claremont Village. The 1970s were perhaps the most anti-urban decade of US history and the village-ification trend grew then with the creation of Arbor, Bixby, Island, North Village Westwood, Orange Grove, Windsor villages — and the renamed Village Green.The ’80s added Baldwin Village and the genuinely village-like Kenneth Village. The ’90s saw the creation of Burbank, Los Feliz, Picfair, and Virgil villages. The 21st century added California, Franklin, Reynier, Silver Lake, and Sports villages. By now, though, “village” is as likely to be slapped on an apartment complex or pod mall as any sort of residential community.

❦

GARDEN APARTMENTS – VILLAGES IN THE CITY

During roughly the same era (especially between 1937 and 1955), Los Angeles also constructed many garden apartments that were, in some ways,“villages in the city.” They include Wyvernwood (1939), Avalon Gardens (1941), Baldwin Hills Village (1942), Hacienda Village (1942), the William Mead Homes (1942), Estrada Courts (1943), Chase Knolls (1948), Silver Lake Garden Apartments (1949), Lincoln Place (1951), and Nickerson Gardens (1954). Documentary filmmaker Maya Santos made a short film about Garden Apartments titledVillages in the City: Garden Apartments of Los Angeles.

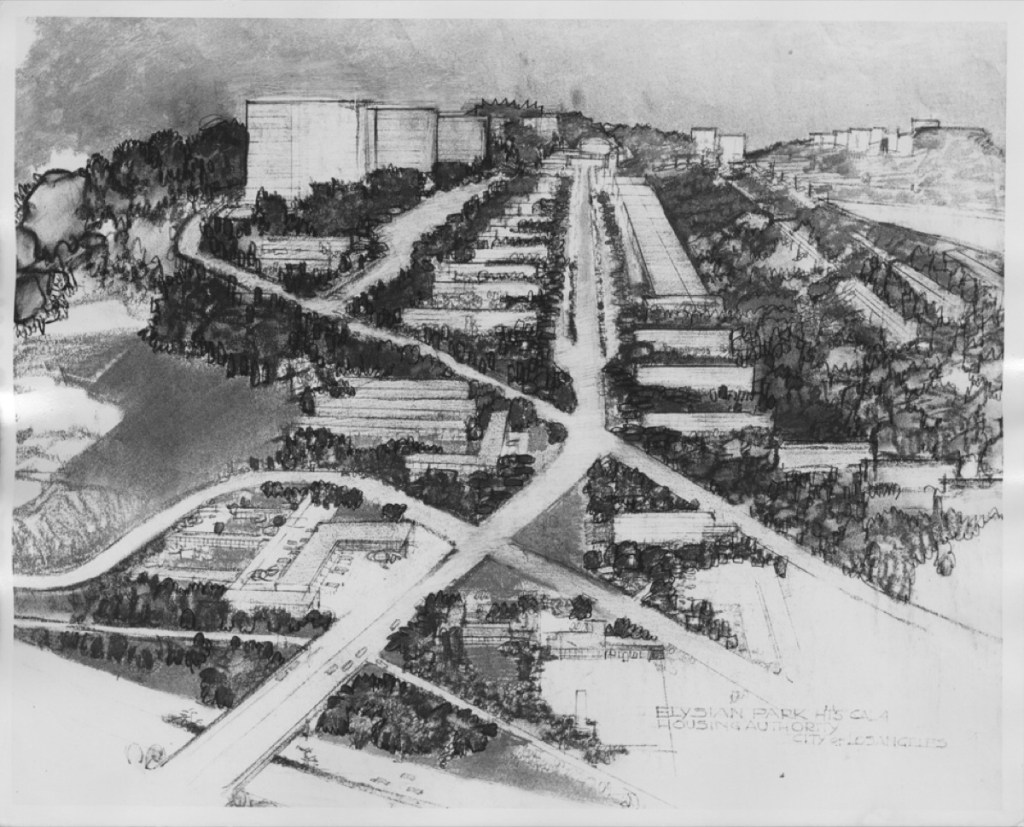

But there’s more to a village than shared green space, light density, walkability, and the ability to “raise a child.” There are also workplaces and commercial spaces – and these villages, like much of Los Angeles, were built to be exclusively residential… which rendered them more like apartments in a park. Nicer than a slum – but not self-sustaining – and not really villages. Popularized in Los Angeles by the Federal Housing Administration,, many of them, too, were public housing projects and, after white GIs were given loans to move to the suburbs and the demographics of the projects changed, the city starved them of services and, neglected, “housing project,” in the American context, shifted from an idealistic term for urban renewal into a heavily stigmatized label and shorthand for urban failure. It seemed like Los Angeles was on the cusp of getting public housing right with the planned construction of the more mixed-use Elysian Park Heights, but right wingers sucessfully stopped the construction of it and subsequent public housing on the grounds that providing homes for war veterans and the poor was “un-American.” Thus, the communities of Chavez Ravine, that had been forcibly evicted and promised new housing, were instead treated to the creation of the vast, neighborhood-dwarfing Dodger Stadium parking lot.

❦

VILLAGE SIMULACRA

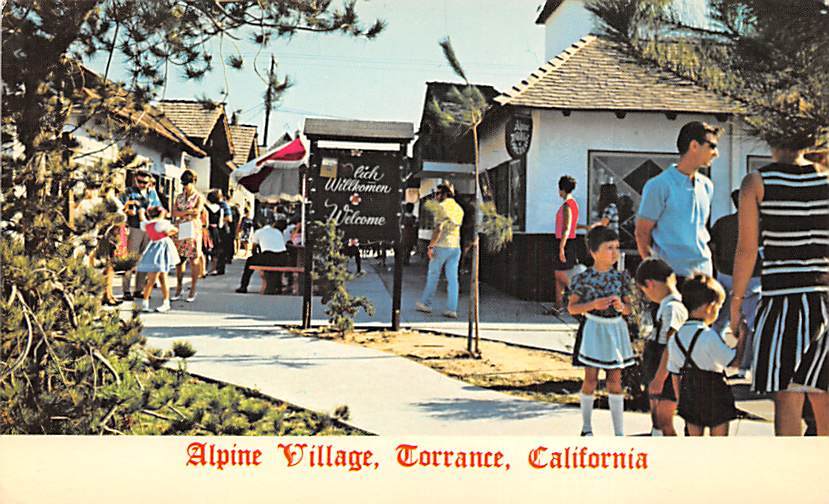

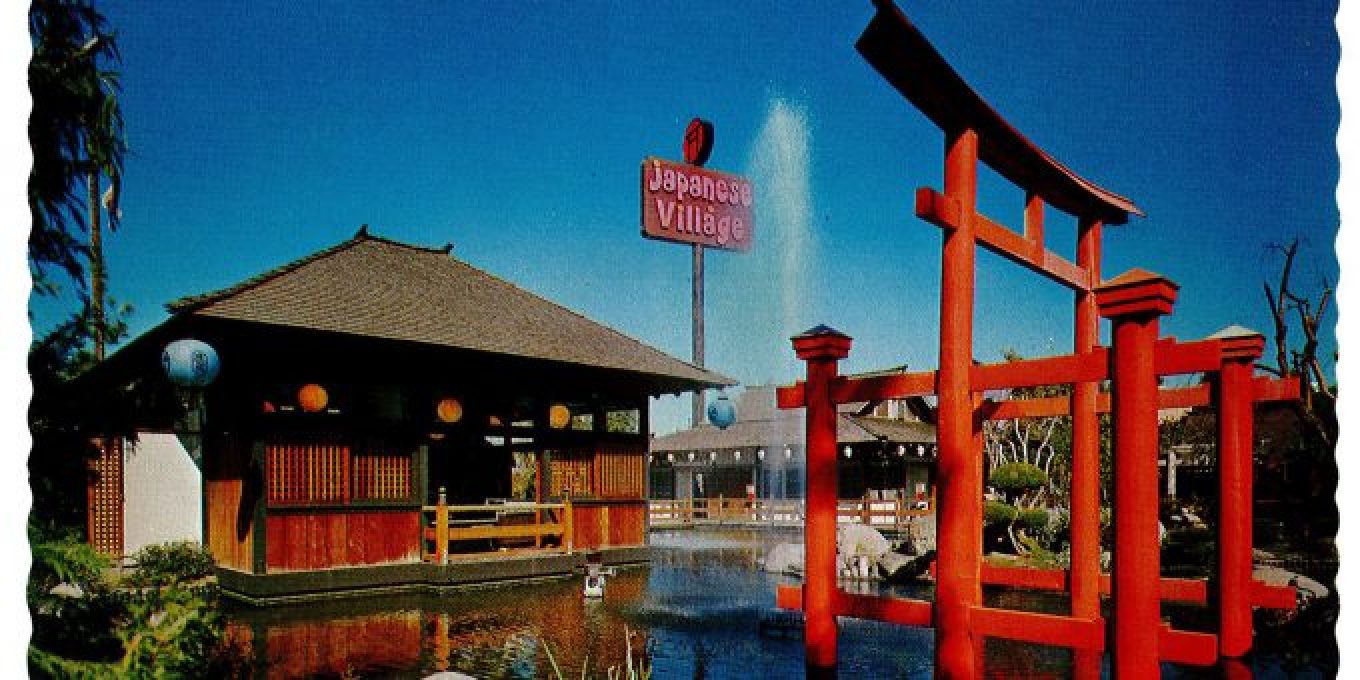

One of the distinguishing characteristics of Los Angeles is its wholehearted and unashamed embrace of simulacra. Many Angelenos care more if things look like something than if they function like them. A cinema that looks like a Spanish Mission on the outside and an ancient Egyptian tomb inside is preferable to a functional Spanish mission. Many Angelenos love spaces that look like villages, too, and, on the whole, they seem more than happy (or conditioned) by car-brain to overlook that a village stroll usually first requires a drive to a multi-story parking garage.

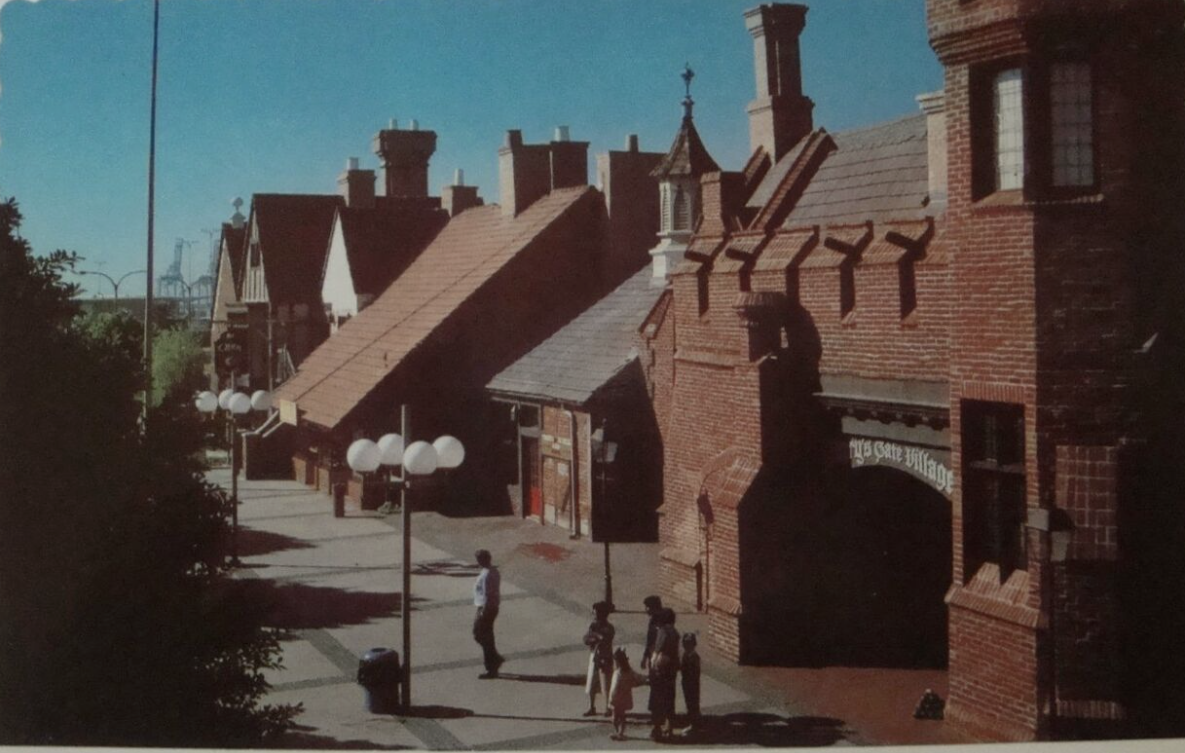

It’s the village as theme park. Consider the kitschy The Americana at Brand, Atlantic Times Square, Chinatown, the Grove, Japanese Village Plaza, Olvera Street, Palisades Village, Plaza del Valle, Two Rodeo, and Universal Citywalk. If we look a bit further, we have Main Street USA, Old World Village, and Pioneertown; all of which, in my view, have acquired a level of authenticity that they never aimed for through stubborn persistence. Just not being demolished is all it takes, in other words, and, sadly, many (Alpine Village, Japanese Village and Deer Park, Ports O’ Call Village) have been closed or demolished by “developers.” They continue to be destroyed, too. Long Beach demolished quaint Mary’s Gate Village in 2025 to create… you guessed it, more car storage. Paving the way for the future!

❦

ACTUAL VILLAGES OF LOS ANGELES

Perhaps it’s the blurred lines between theme parks, amusement parks, shopping centers, apartment complexes and urban commercial districts that lead to us overlooking that there are also quite a few places that approach actual village status in Los Angeles. Not all succeed. There are rural subdivisions like Antelope Acres, Big Rock Springs, Halsey Canyon, Juniper Hills, Kagel Canyon, Longview, Lopez Canyon, Saratoga Hills, Sleepy Valley, and Val Verde where even the simplest errand requires lugging around a car.

Closer to actual villages are the phantom villages that appear with names on maps but, from the ground level, feel not particularly like anywhere in particular. Some of them are, in effect, living ghost towns where a single anchoring establishment closed or burned down ages ago, orphaning the surrounding, remaining homes. Others were real estate scams that, like a lot of scams, never quite succeeded in getting off the ground. They all have village potential, though, because zoning exclusively for “single family homes” hasn’t yet smothered all hope in and around them. I’m talking about places like Big Pines, Del Valle, Desert View Highlands, Holiday Valley, Largo Vista, The Oaks, Oban, Paradise Springs, Pine Store, Quail Lake, Ravenna, Redman, Sandberg, and White Heather.

There are also places like Castaic Junction and Gorman, that, though small in size and population, feel less like villages than outgrowths of freeway rest-stops. Just as population size doesn’t, on its own, determine whether a place is a city, a town, or a suburb; nor do they necessarily make a place a village. Otherwise, we’d think of under-inhabited communities like Commerce, Industry, and Vernon as villages rather than, say, noxious-business-friendly industrial hubs that function more like private corporations rather than the municipalities they technically are. If you really want to visit places that truly function like villages inside of Los Angeles, there are at least a few. I have no issue with characterizing Cornell, Elizabeth Lake, Green Valley, Lake Hughes, Leona Valley, or Valyermo as villages. If, though, your quest for village life really just comes down to finding a home where the antelope roam, and the on-street parking is free everyday, pretty much any of these places will do.

❦

THE VILLAGE GREEN DESTRUCTION SOCIETY

With all of these villages and potential villages – and the Angleneo’s great love of anything with even “village” in the name – it is ironic that so many work so against allowing anything village-like to actually arise in their backyards rather than the Santa Monica Mountains or Antelope Valley. They oppose replacing car storage with housing in the name of maintaining “neighborhood integrity.” They claim that a BRT line will obliterate the “small town character” of a neighborhood that began as a streetcar suburb. They push the downzoning and parking mandates that killed the very bungalow courts they also want to see preserved. These were the people who passed the “slow growth” Proposition U less than a year after Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim overtook New York-Newark to become the most densely-populated urban area and two years after Los Angeles overtook Chicago to become the country’s second-most-populous city. The tide is finally turning, again.

In order to illustrate the limits of his powers to his flatterers and courtiers, the 11th-century Danish King of England, Cnut the Great, had his throne set on the beach and purportedly commanded the waves, saying: “Thou art under my dominion… I command thee, therefore, not to rise on to my land, nor to presume to wet the clothing or limbs of thy master.” To the horror and astonishment of his followers, the tide rose, and then, point proven, the king exclaimed “Let all the world know that the power of kings is empty and worthless, and there is no king worthy of the name save Him by whose will heaven, earth, and sea obey eternal laws.” That’s a bit what it’s like trying to shrink a metropolis that’s busting at the seams… not that we can’t at least credit (or blame) slow-growthers for the affordable housing and unparalleled homelessness crisis. Despite the efforst of the NIMBYs and urban-anti-urbanists. Measure S was rejected in 2017. Despite the city dragging its feet on its own mobility plan, HLA was passed by a majority of voters in 2024. And despite the efforts of the mayor and most of City Council, SB 79 was approved in 2025, allowing something that was standard in Los Angeles a century ago – the existence of modest housing near mass transit.

When we picture what it is about villages that we actually crave – it’s not just thoughtful architecture, public squares, pedestrian plazas, humming streets, and eclectic mix of shops and homes – it’s also, most importantly, respite from car-dependence. It’s never having to walk across a surface parking lot. And yes, even in Los Angeles that’s possible – despite the annoying persistence of the tired and increasingly unrecognizable narrative that still dominates media accounts and stereotypes.

You can’t go a day without hearing Los Angeles described as “the car capital of the world,” What is that even supposed to mean? The car wasn’t invented here. Cars haven’t been manufactured here in decades. There are 26 cities in Los Angeles County with higher rates of auto ownership than Los Angeles. Car capital of the world? Los Angeles isn’t even the car capital of Los Angeles. You will hear, too, that Los Angeles was built around the car – when, in fact, it was built around the streetcar and only deformed around the private automobile. You will be told, with unearned authority, that, actually, you cannot live in Los Angeles without a car – even though 30% of Angelenos don’t drive. If you, like me, have happily not owned a car in over decades, these people will grow red in the face with anger rather than appreciation that you’re not contributing, with them, to bad traffic and worse air. They can’t appreciate that because, I assume, your car-free or even car-light existence is a refutation of a central lie that they tell themselves – that is that only with car-dependency can one experience freedom and that $14,000 a year, annually, is a small price to pay for it.

❦

YOU DON’T LOOK A DAY OVER 175

So, on Los Angeles County’s 176th birthday, I invite the reader to celebrate Los Angeles, to dream of what we might be – and to learn… to learn from history, to learn from mistakes, to learn from other cities, to learn from villages, to learn from each other… and to dream both bigger and smaller. If you’re here and you’re looking for suburbia, on the other hand, you may find it for now – but if your soul really craves bleak Ballardian isolation and the romance of car-dependency, for your sake and ours, you might seriously want to start looking for somewhere both less urban and less villagey. Take it from me — someone who has lived in cities, suburbs, college towns, and the middle of nowhere — and undestood, at least theoretically, the appeal of them all. Shelbyville is supposed to be lovely this time of year!

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always open to paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hey Freelancer!, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, the Los Angeles County Store, Sidewalking: Coming to Terms With Los Angeles, Skid Row Housing Trust, the 1650 Gallery, and Abundant Housing LA.

Brightwell has been featured as subject and/or guest in The Los Angeles Times, VICE, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, LA Times 404, Marketplace, Office Hours Live, L.A. Untangled, Spectrum News, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, Notebook on Cities and Culture, the Silver Lake History Collective, KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, All Valley Everything, Hear in LA, KPCC‘s How to LA, at Emerson College, and at the University of Southern California. He is the co-host of the podcast, Nobody Drives in LA.

Brightwell has written a haiku-inspired guidebook, Los Angeles Neighborhoods — From Academy Hill to Zamperini Field and All Points Between; and a self-guided walking tour of Silver Lake covering architecture, history, and culture, titled Silver Lake Walks. If you’re an interested literary agent or publisher, please out. You may also follow on Bluesky, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, iNaturalist, Instagram, Letterboxd, Medium, Mubi, Substack, Threads, and TikTok.

.

Thanks for this awesome dive into Los Angeles history. What a great birthday present to the city. And the county.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And especially thanks for the info on the Chumash and the Tongva. I never really understood the difference before.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Eric,

Thank you for this! Love the debate about who gets to claim to be an Angeleno and I agree with you that it’s not strictly the city but the greater metro area. (Does that include parts of the Inland Empire, though, where I was born? I like to think it does).

My family has been in the greater Los Angeles area for more than a century. My great-great-grandparents moved from Juarez, Mexico to Alhambra in 1905, and my other great-grandparents lived everywhere from Bunker Hill, Silver Lake, Alhambra, to the east LA projects (Aliso Village).

They eventually kept moving out east as they earned more money and started having kids (ie Pico Rivera, La Puente and Hacienda Heights, where my parents were raised).

Much love to a great city and county!

Melissa

Melissa M. Montalvo melmontalvo1@gmail.com (480) 516-4763

–

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love that story — makes me wonder about another question — how long does someone “have to” live in Los Angeles before they’re an Angeleno? Personally, I think its up to the person (and not as important as people make it out to be, which isn’t even that important, I don’t think). But your long history in the region got me thinking because my maternal grandfather hoboed out to Los Angeles around 1936 and slept in a park until he got a job in Panama. I wonder if he ever thought of himself as a resident of Los Angeles? In his case, I kind of doubt it. He had run away from Iowa and he returned there and lived there for most of his life. Just thinking outloud, really.

LikeLike