This piece was originally written for “Ask Silver Lake.” “Ask Silver Lake” is dedicated to exploring the history and insights of our community. If you have questions or ideas you’d like us to consider, please drop a comment or send them to outreach@silverlakenc.org.

On 10 October 2025, the Abundant and Affordable Homes Near Transit Act was signed into law by California Governor Gavin Newsom, better known, perhaps, as SB 79. Although the bill was opposed by Los Angeles mayor Karen Bass – it was supported by Silver Lake’s City Council representatives, Hugo Soto-Martínez and Nithya Raman, Assembly Member Jessica Caloza, and State Senator María Elena Durazo. The goal of the to reduce car dependency and pollution and to address the housing crisis by establishing state zoning standards to allow for the construction of higher-density housing near major mass transit stops. It will take effect on 1 July 2026.

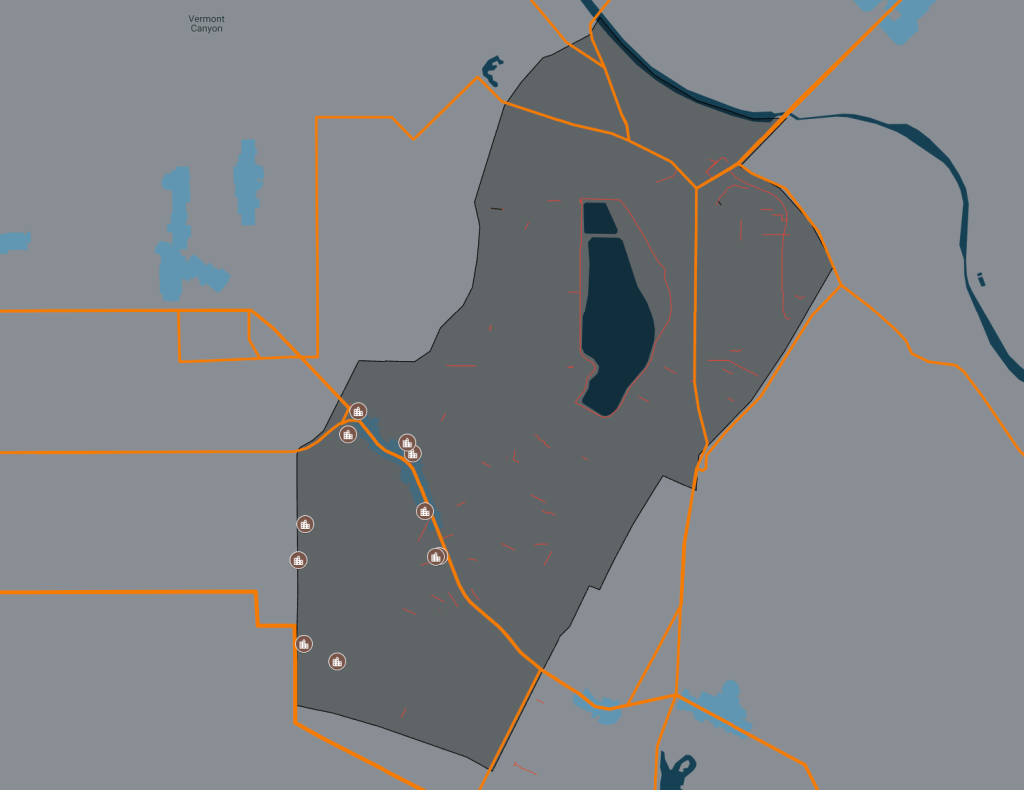

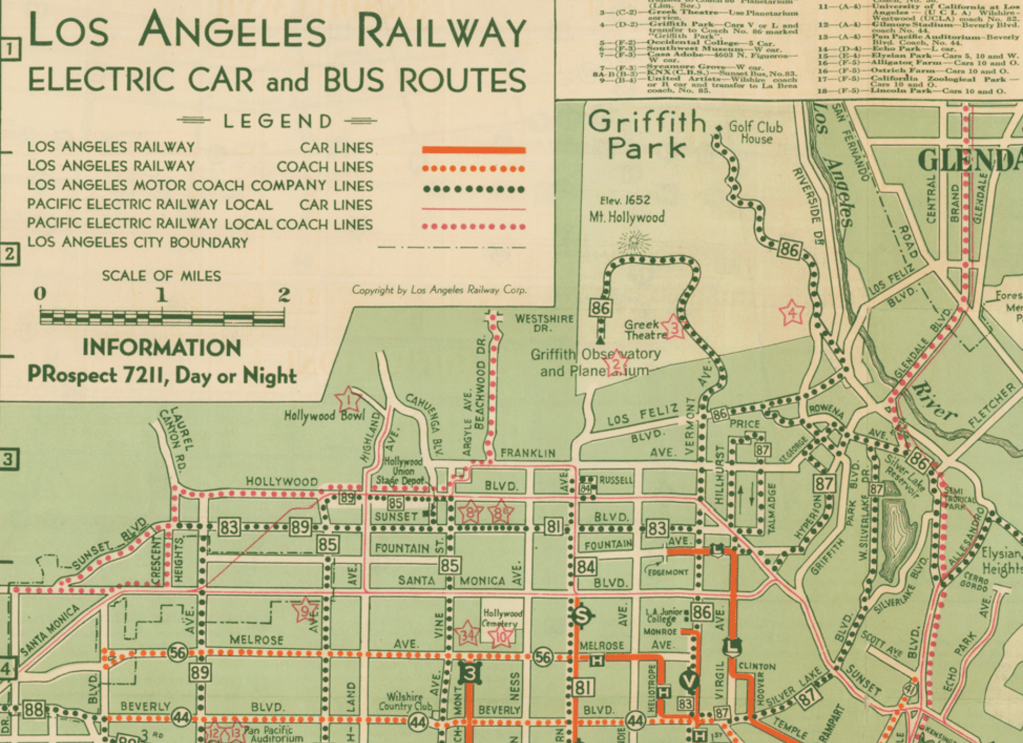

There are two categories of “major mass transit stops.” Tier 1 includes subways and commuter rail stations with frequent service – neither of which are found within Silver Lake. Tier 2 includes light rail and Bus Rapid Transit stations and stops for buses with dedicated lanes or headways of fifteen minutes or less – which are found on Vermont Avenue in nearby East Hollywood.

That means that the construction of buildings up to 65 feet (20 meters) with no dedicated car storage could soon arise along Silver Lake’s western border, Hoover Street. Silver Lake has never had six-story buildings before and some worry that their existence will negatively impact the community’s “neighborhood character.” That said, Silver Lake has already been home to four and five story mid-rise apartments with no dedicated parking for a century.

“Neighborhood character” has been evoked in community meetings since at least the 1960s — but what is meant by it remains open to interpretation. “Preserving neighborhood character” has been used to oppose industrialization and construction of freeways in residential neighborhoods – but also to exclude certain classes and ethnicities. It’s been used to protect historic structures from demolition – but also to oppose any and all construction – especially of Transit Oriented Developments or, “TODs.”

The modern concept of the TOD was formalized in the late 1980s by San Francisco-based architect and urban planner Peter Calthorpe, in the wake of downzoning that reduced the residential capacity of Los Angeles from ten million to 3.9 million. According to The Homeowner Revolution: Democracy, Land Use and the Los Angeles Slow-Growth Movement, 1965-1992 (Greg Morrow, 2013), that downzoning was the result of a coordinated series of efforts, including the adoption of the 1974 General Plan, 1978 Open Space Element, and 1978 AB 283 Consistency Program — and solidified by 1986’s Proposition U. Downzoning’s proponents argued that multi-tenant structures were “out of character” with the neighborhoods in which they’d previously been legal. Critics countered that confining the residents of a renter-majority city to just 20% of residential areas while setting aside 80% for R1 zoning (“single family homes”) was socioeconomic segregation. The downzoners’ wins defined the “slow growth” of the 1970s and ’80s but more recent ordinances like Citywide Housing Incentive Program (CHIP — adopted in 2025) and SB 79 are designed to restore residential capacity.

Regardless of one’s views concerning zoning, SB 79, and TODs; during the building boom of the 1920s, Silver Lakers witnessed the construction of several large apartment complexes that included, in most cases, no on-site parking and were positioned along the mass transit lines then operated by Los Angeles Railway (LARy) and Pacific Electric Railway (PE) – and now located along lines operated by the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority (Metro). It’s hard not to see these four and five-story mid-rises, retrospectively, as TODs. Having been features of the neighborhood for a century – they would seem to be contributors to Silver Lake’s neighborhood character. In this charitable light, SB 79 could viewed not so much as a radical disruption of Silver Lake’s neighborhood character, but as a restoration and continuation of it.

Silver Lake first began to coalesce as a neighborhood in the 1910s, a few years after the completion of the Silver Lake Reservoir in 1908. Before that it was usually characterized as East Hollywood, Los Feliz, Westlake – or identified with smaller tracts like Dayton Heights, Edendale, and Ivanhoe. Before Silver Lake, the neighborhood was characterized by small farms and the large Rancho Los Felis to the north. Transplants from cities like Boston, Chicago,Kansas City, and St. Louis began flooding the area in the 1880s and buying lots along the streetcar lines that were, in many cases, owned by the same men who were developing the city’s streetcar suburbs.

By the 1910s, Silver Lake was already experiencing a rise in construction of large apartment buildings. The 24-unit, three-story Reiter Arms (designed by and named after its builder, Frank Reiter) has stood at 1042 Sanborn Avenue since 1913. At the time, that area was known as Manzanita Heights, a name, which, like the building’s, was soon mostly forgotten. For whatever reason, almost all were long ago re-branded with generic names. The Reiter Arms, for example, now goes by the Sanborn at Sunset Junction.

The history of modest transit-oriented four and five-story mid-rises is comparatively ignored by architecture historians and preservationists alike. They are also, in too many cases, neglected by their landlords. Finally, although the vast majority of Angelenos are apartment renters, they, too, are frequently stigmatized by both the home-owning minority and legacy media.

Searching through newspaper archives for historical tidbits about these buildings may risk reinforcing some of those classist stereotypes – but only because local print media has always been focused on the sensational and thus, most of the tenants only made the papers for sensational reasons (crimes, car crashes, deaths) – or, alternately, for reasons too mundane to interest most modern readers (birth and wedding announcements). That said, I’ve done my best to provide a balanced account of some of their more colorful, and long-gone Silver Lake stakeholders who lived in these humble towers.

THE PLAZA/PENDENNIS APARTMENTS

The oldest of Silver Lake’s historic mid-rises is probably the four-story, 22-unit, Mission Colonial Revival-style Plaza Apartments, which opened at 1600 Childs Avenue in April 1924. By that time, the Los Angeles Ostrich Farm Railway and its successor line, that ran up Childs Avenue, had ended service. PE’s San Fernando Valley, Hollywood, and South Hollywood-Sherman lines continued to travel along Sunset Boulevard for roughly another 25 years. Now it’s served by Metro’s 2 and 4 lines. The junction of these lines, below the Plaza Apartments, formed the Sunset Triangle Plaza – still Silver Lake’s only pedestrian plaza since its creation fourteen years ago.

Upon the Plaza’s opening, rents started at $50 per month (about $955 adjusted for inflation). In October 1924, the Plaza Apartments were listed in The Los Angeles Times as the Pendennis Apartments, perhaps a misprint – or maybe the building was briefly taken over by a William Makepeace Thackeray fan. Subsequent listings referred to the building as the Plaza Apartments until the 1930s. Childs Avenue, meanwhile, was renamed Griffith Park Boulevard in 1925.

THE MILHOLLAND APARTMENTS

Permits were issued for construction of the mixed commercial and residential (eighteen units) building with the ornate façade at 4013 West Sunset Boulevard, the Milholland Apartments, in May 1924. It was built by R. W. Clark for owner, I.G. Simmons. Who it was named after is unclear, but the most prominent Milholland in Los Angeles was suffragist, lawyer, and peace activist, Inez Milholland, who died in Los Angeles whilst speaking for women’s rights as a member of the National Woman’s Party, in 1916. It has eighteen residential parking units above the commercial level, only three of which rise above Sunset. The presence of vault lights in the sidewalk indicates the existence of a lower level and, indeed, there’s another story below that exits onto Wit Place.

While loads of establishments make dubious claims about having been a speakeasy to make them seem more interesting – here, at least, those claims are true. In September 1927, resident Thomas Perkins was busted for possession of fifteen gallons of wine. He claimed that the wine was for personal consumption and the enjoyments of a couple of Christmas visitors. Perhaps that was true – but in March 1929 he was again arrested, this time for possession of $7,000 worth of liquor (roughly $135,000 today).

In the 1930s, the ground floor was home to a taxidermist, Joseph B. Colburn, who commit suicide amongst the stuffed animal corpses on 9 May 1936. He was buried at Forest Lawn. The decades that followed saw furniture stores, vintage shops, and at one time, Giant Robot. In 2023, Donald Glover’s boba joint, Jellyman, took over the space vacated by Blossom Vietnamese Restaurant.

The building is also notable for featuring hand-painted advertisements – a tradition stretching back quite a few years – a fact evinced by the faded ghost sign advertising Emerson’s Bromo-Seltzer. Emerson’s product was developed in 1889 to treat upset stomachs and headaches but was discontinued in 1975 due to toxicity concerns. Today, however, the site of two painters creating a new advertisement remains a welcome, if common, one.

THE ALFRED LEE APARTMENTS

The 26-unit, Alfred Lee Apartments at 3205 Descanso Drive opened in 1927. Like the Reiter Arms, the Alfred Lee may’ve been named after its builder; the name is so common as to elude easy research. A sign advertising the building’s name remained until at least 1985 but was removed by 1990. For quite a few years, there was a mural painted atop the heighest point of the building of a woman and the name “Descanso Artiste,” which the building was then known as. It was painted over in or shortly before 2024.

Real estate folks have claimed, in the past, that it was originally a “vintage motel.” Motels, by definition, though, are car-oriented and the Alfred Lee was built without any car storage. Chief among the Alfred Lee’s amenities, in fact, was its proximity to two PE lines – today it’s served by two Metro routes. Motels, too, are low-slung and not the tallest building in a community, which the five-story Alfred Lee has been for nearly a century. Finally, how a brand new construction can open as “vintage” anything is beyond my understanding.

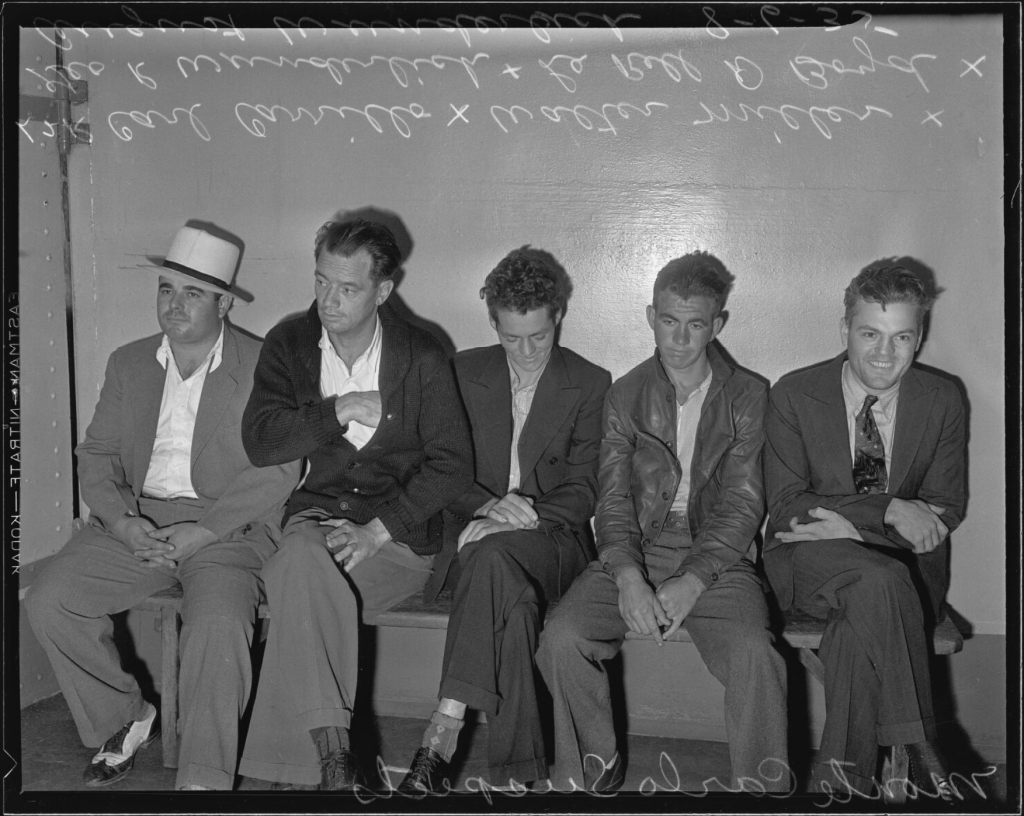

A couple of the building’s most unsavory inhabitants were two bad brothers, the Wunderlichs (also spelled “Wonderlichs”), who came to Los Angeles from Missouri. Younger brother, George Robert Wunderlich, was arrested for shoplifting, counterfeiting, and possession of a stolen machine gun in 1929. August was arrested for bootlegging in 1931. In 1935, both were arrested for piracy – for their role in robbery of the SS Monte Carlo, a ship that hosted gambling and prostitution off the coast, in international waters until it wrecked in 1937. It’s still visible at low tide near Coronado Shores in San Diego. George couldn’t be connected to the crime and died in Los Angeles in 1980.

Another colorful resident of the Alfred Lee was samurai sword collector Bernard Lucas, who was profiled by The Los Angeles Mirror in 1951 for the unique hobby that he picked up during his military service in Japan. And if you’ve ever seen a ghost at the building, try to determine whether it’s Juanita Achee or Josephine Mitchell, both of whom died there in fires, in 1957 and ‘59 respectively.

THE CLIFFDALE APARTMENTS

The fifty-unit, four-story Cliffdale Apartments were built in 1927. Located at 836 North Sanborn Avenue, there’s a bit of a slope along the street but you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who’d describe its location as either “cliff” or “dale.” There is a small garage door but, apparently, no car storagƒlos e. At the time of its construction, the closest transit line was LARy’s L Line, which traveled along Hoover and Melrose avenues. Today, that route is travelled by Metro’s 10 line.

In 1931, one of the Cliffdale’s residents was Glen Arthur Edmunds. Edmunds and his band, the Collegians, had a program on KFI until 1931, when he moved KGFJ with his new Glen Edmunds Orchestra. That October, Glen struck the proprietor of the Mary Helen Tea Room, Mary Helen Kamp, with his car in a collision The Los Angeles Evening Citizen characterized as an “auto mishap.” She escaped serious harm but just over a year later, his wife, Dolly, divorced him on account of his “addiction” to “wild parties.” Edmunds rebounded, remarried a woman with the improbable name of Della Dame, and moved to Wilshire Center, where he died at the age of 44 in 1950.

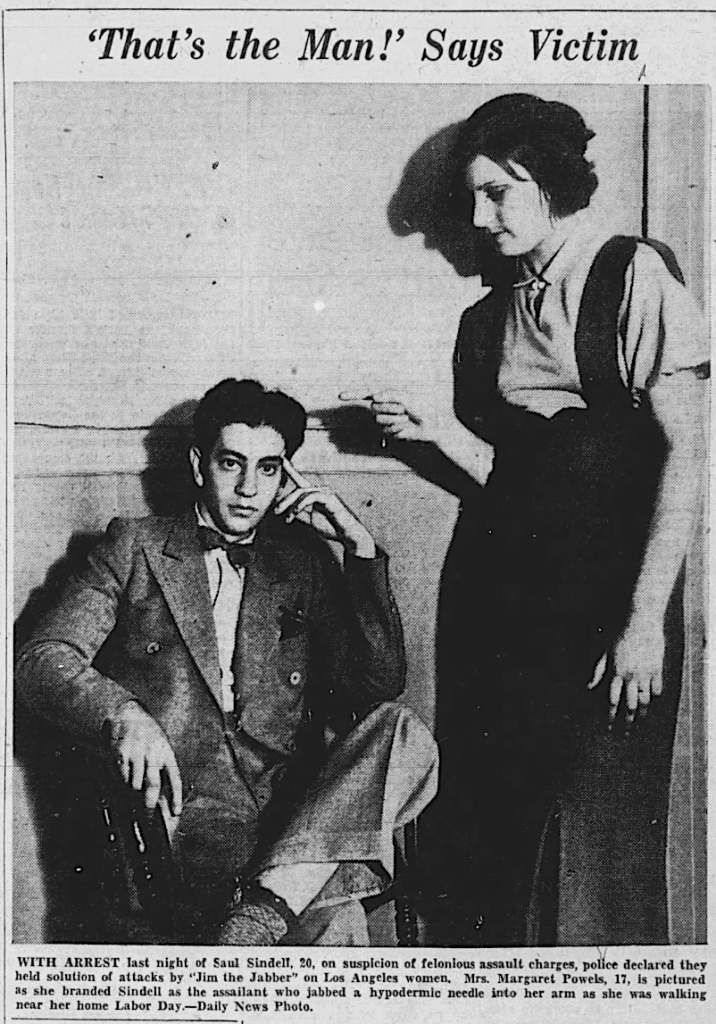

A truly creepy villain the press nicknamed the “needle pusher,” “slinking sadist,” “jabber fiend,” “Jim the Jabber,” and “Jake the Jabber” was terrorizing the area in the 1930s. He stabbed, non-lethally, at least a dozen women with in the area. In 1935, he attempted to attack a woman who was protected by a resident of the Cliffdale, Henry Briggs, who described the dastard’s weapon as a darning needle attached to a broom handle. Several suspects were taken in before Saul Sindell, “son of a wealthy Cleveland textile manufacturer,” who lived in a home at Myra and Effie was arrested, charged, and sentenced at the end of the year.

There were a couple of other high profile residents of the Cliffdale Resident Agnes Murphy was arrested in 1938 for working as a bookie. The body of 45-year-old salesman named Leonard C. Williams was discovered by one of the building’s maids in 1940 after he shot himself and left a note, reading “The squeeze is on and I figure this is the only way out for you and your friends financially. I love you–Len.”

In 1958, one of the units was briefly the residence of Quay Cleon Kilburn, one of the FBI’s Most Wanted. Kilburn was a “habitual criminal” who’d served time for desertion, bad checks, bank robbery, car theft, and parole violation before escaping from Utah State Prison. He was arrested at his new home in the Cliffdale. After serving his sentence, he was again added to the FBIS’s most wanted in 1964, for embezzlement and robbery, and was again arrested. His wife died under violent and suspicious circumstances in 1973. Kilburn died in 2008.

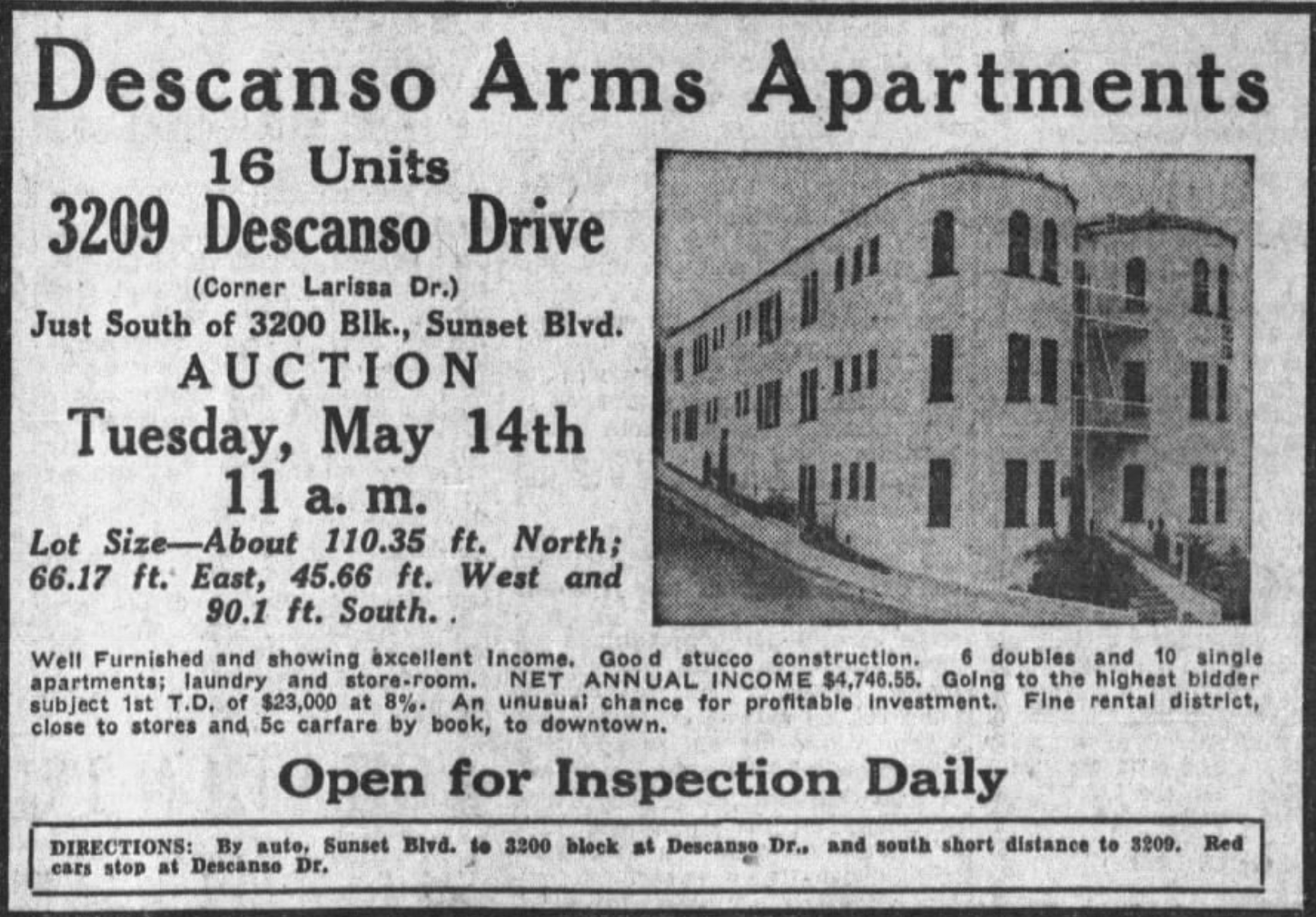

THE DESCANSO ARMS

The sixteen-unit Descanso Arms opened next door to the Albert Lee, at 3209 Descanso Drive, in 1928. It’s only three stories tall. With apologies to some of the hillside, four-story buildings I’ve left out of this piece because they drop below the streets on which they’re located — I reckon the Descanso Arms is sufficiently tower-like to warrant inclusion

In 1945, a tenant and ex-marine named Jobert Williams took it upon himself to dress as a woman, lure men they called “mashers” who targeted and annoyed women. When a teenager said to one of them, “hello honey,” Williams and his cohort, Robert Blanton, attacked the teen – an act for which they were celebrated in The Los Angeles Times. The victim of their attack was booked by the police on suspicion of burglary.

Another resident of the Descanso Arms was Robert H. Sims, who had a short-lived side gig of sorts with The Los Angeles Mirror in 1949. In August, he submitted an invention idea for a collapsible mop and broom to the paper’s column, “My Wife Wants.” He was paid $5. In September, he submitted his recipe for baked fish mold for the column, “My Best Recipe,” for which he earned another fiver.

THE HOLLY MANOR APARTMENTS

Permits were issued to Jambor Construction Co. Inc. for the construction of the 36-unit, four-story, Holly Manor Apartments in 1927. The handsome, red brick, Tudor Revival-style building opened at 1055 North Sanborn Avenue in February 1928.

In 1932, resident and city health department employee — and bootlegger — Dr. Samuel Hughes, was arrested there after selling two bottles of rum to an undercover officer. In 1933, former aviator and Angelus Temple organist Walter G. Radcliffe was living at the Holly Manor when he was charged for burgling rugs, pillows, and other items from the cabin of a woman who’d taken him there with her mother after attending several of his concerts. In 1939, Holly Manor resident, Billy Brandt, won a Los Angeles Times contest for amateur photographers with his photo of a child looking into a garbage can

In another award-winning recipe submission from Silver Lake mid-rise dweller, R. G. Wilke won $5 for his recipe for Roquefort dressing. He explained to The Los Angeles Times that he was “ of the male extraction who likes to play games in the kitchen.” He added that his wife had an “unusual tolerance” for his “culinary efforts” and claimed that they both enjoyed the dressing “for special occasions or when we feel just a bit jaded.”

THE CRESTMONT ARMS

The 32-unit, four-story, brick Crestmont Arms opened at 1525 Griffith Park Boulevard in 1929. For such a large building, its mentions in the papers are, for the most part, refreshingly banal. For example, in 1930, J. Whyte Evans (resident of unit no. 105) was noted as a card-carrying member of the California Avocado Association. In 1958, a young resident named Gregory Appleby was awarded “most improved boy” by St. Paul’s Cathedral. On the other hand, there was a furrier, Louis Thurn, who belonged to a “film burglary ring” that targeted the homes of Hollywood stars including Barbara Stanwyck, Richard Barthelmess, and others.

THE SENATOR ARMS/LOMBARD

The 53-unit, four-story, Mediterranean Revival-inspired Senator Arms opened at 3408 West Sunset Boulevard in 1929. They were built for owner O. McGinnis, who operated one tower as apartments and the other as an hotel. The rooms were furnished by a company called Walkers Inc. At the grand opening of the Senator Arms, in November 1929, the owners listed its many amenities. There was an on-site hostess, maid and janitor service, steam heating, gas stoves, electric refrigeration, and, of course, proximity to the streetcar line on Sunset. Initial rents at the Senator Arms started at $30 a month (roughly $575 today).

Around 1937, the building was renamed the Lombard Apartment-Hotel, which it remained until at least 1955. It was during the Lombard years that the building appeared in the news. In 1941, salesman named Christopher Sproul shot a baker, Anthony Piscatelli, there when he found the baker paying a visit to his estranged wife and Lombard resident, Penelope. In 1944, resident Joseph Seminar was robbed of $80 in his residence there by Robert F. Brown and William Baker. Finally, in 1962, 25 (or 27) year-old resident and mother, Theresa Dandrea, was arrested for burglarizing twenty local churches. She told officers that “it just got to be a habit.” The Lombard was renamed Silver Lake Towers around 2021 — when the buildings received a bold, new, blue and white paint job.

THE GREYSTONE APARTMENTS

The 30-unit, four-story Art Deco-style Greystone Apartments at 600 Imogen Avenue were completed in 1930, the year Los Angeles became one of the first major US cities to adopt parking requirements for new apartment buildings. Construction presumably began before the mandate passed because no car storage was included in the apartments, which were located on LARy’s L Line (and now served by the 10).

In 1942, a resident and fight promoter named Harry Randolph was arrested – along with his co-conspirators, Alex Piasckik and Cecil Imes – for robbing wealthy thoroughbred owner, actress, and stuntwoman, Anita King, at her Benedict Canyon home. King had gained fame, in 1915, as the first woman to drive a car across the US unaccompanied by a man. The thieves absconded with jewelry, furs, and $20,000 in cash. A few weeks later, Randolph was arrested near his gym.

THE FERNCLIFF APARTMENTS

The 32-unit, four-story Ferncliff Apartments, at 760 North Hoover Street, also opened in 1930. Located at Hoover, where the Spanish diagonal grid of the old city and Jeffersonian grid of the American era collide, the building is striking, with a flatiron-style that makes it an icon of the neighborhood. It was one of the first apartments with an in-building garage of ten parking spaces.

In September 1932, 32-year-old resident and beauty parlor operator, Florence A. Stack, fell or jumped from the roof. Miraculously, she survived the fall which was cushioned by bushes. Unfortunately, however, she was struck and killed by a truck driver almost a year later to the day. In 1945, stenographer and resident Leroy Anderson was arrested on charges of “masquerading as a woman” when he was dragged to the police station by a transphobic vigilante. Apparently Anderson didn’t know about the “masher” defense.

The building was long ago renamed “Hepburn Manor,” after actress Katharine Hepburn, who real estate people have claimed both built the building and lived in it. The building’s interior is decorated with images of the actress and stenciled quotes attributed to her. The building’s website says that it was “established in 1919,” when the then-eleven-year-old was living in Hartford, Connecticut. After she became an actress, she moved from Manhattan to a grand mansion in Beverly Hills and it’s hard to understand why she’d bother renting a modest apartment in Silver Lake. Then again, there also claims that Betty Grable lived there – in addition to in her mansions in Beverly Hills and Bel-Air.

THE BELLEVUE ARMS

The last of the historic TODs was the Bellevue Arms, a four-story, 31-unit Art Deco-style apartment. It was completed in 1936, well after the parking mandates were in place requiring a parking spot for every unit. However, permits for its construction had been granted all the way back in 1930. Like the Ferncliff, it does include a small ground-floor garage but it’s unclear, from the outside, how many cars, if any, can fit in it. The lobby and interiors have a bit of a Streamline Moderne feel, with ship-like railing. The Bellevue Arms’ most infamous tenant may’ve been Anthony C. Deagle, who, with his partner, Margo Lukov, was arrested in 1944, after having stolen morphine intended for the use of the armed forces.

The 1930s marked a shift toward “auto-oriented” planning – which radically deformed the neighborhood character. Just as parking mandates made it prohibitively costly to construct bungalow courts, so, too, did they spell the end of construction of these modest transit oriented mid-rises. A wave of construction of large did return in the 1970s with the construction that continues into the present. Unlike the historic TODs, though, these constructions have all been CODs — or “Car Oriented Developments.” They sacrifice the entire ground floor for car storage — as well as any aesthetic considerations. They continue to rise next to freeways; where the air is toxic, the noise is loud, and the land is comparatively cheap.

This development pattern may well change with mass transit upgrades allowing for the construction of mid-rises away from the freeway fringe to the community’s commercial corridors. As the Abundant and Affordable Homes Near Transit Act (SB 79) takes effect this July, the discourse surrounding “neighborhood character,” just like a six-story building, will undoubtedly reach new heights. If you have opinions you’d like to make known on the subject, consider becoming involved with the Silver Lake Neighborhood Council’s Urban Design & Preservation Committee and/or the Transportation and Mobility Committee.

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always open to paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hey Freelancer!, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, the Los Angeles County Store, Sidewalking: Coming to Terms With Los Angeles, Skid Row Housing Trust, the 1650 Gallery, and Abundant Housing LA.

Brightwell has been featured as subject and/or guest in The Los Angeles Times, VICE, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, LA Times 404, Marketplace, Office Hours Live, L.A. Untangled, Spectrum News, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, Notebook on Cities and Culture, the Silver Lake History Collective, KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, All Valley Everything, Hear in LA, KPCC‘s How to LA, at Emerson College, and at the University of Southern California. He is the co-host of the podcast, Nobody Drives in LA.

Brightwell has written a haiku-inspired guidebook, Los Angeles Neighborhoods — From Academy Hill to Zamperini Field and All Points Between; and a self-guided walking tour of Silver Lake covering architecture, history, and culture, titled Silver Lake Walks. If you’re an interested literary agent or publisher, please out. You may also follow on Bluesky, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, iNaturalist, Instagram, Letterboxd, Medium, Mubi, Substack, Threads, and TikTok.

Eric, Thanks for another fascinating look at LA. Lots of interesting facts here. Honestly, though, I don’t think SB 79 will make any difference in promoting transit ridership. There have been a number of bills passed in Sacramento since 2017 aimed at increasing density near transit hubs. Locally, we also had the Transit-Oriented Communities Guidelines. Unfortunately, transit ridership has continued to fall. According to Metro stats, 2025 Total Estimated Ridership was 237,970,649, down from 299,561,445 in 2019. And 2019 was way down from 2014 Total Estimated Ridership of

367,905,268. Also, you state that Proposition U reduced LA’s zoned capacity from 10 million to 4 million. Do you have a source for that? I looked at the EIR for the Housing Element from the 1995 General Plan, approved after Prop U. It starts with an existing 1,299,963 dwelling units and projects that the 1995 plan would add 1,566,908 more units for a total of 2,866,871 dwelling units. If we multiply that by 2.9, the average household size in LA County, we get a potential 8,313,925 residents. I’ve seen this assertion about Prop U before, but I’ve never seen any calculations to back it up. Do you know how the 4 million figure was arrived at?

LikeLike

Thank you and I really appreciate your feedback.

I suspect that there are all sorts of reasons for Metro’s ridership fluctuations – and I also suspect that most of the dips stem from dwindling affordable housing stock, slow speeds, and infrequent service. There are lots of other factors, too, both good and bad: AB 60 (which led to 600,000 non-resident citizens getting drivers licenses), the rise of ride-hail services, fluctuations in gas prices, Metro redirecting money from bus service to rail expansion and highway widening, growing numbers of walkers and cyclists, and the LAPD-fueled media fixation on crime near and on Metro properties. I don’t think it’s because Angelenos simply won’t use mass transit. Roughly 80% of Angelenos who primarily drive say that they do so because they have no practical alternative.

If you’re a low-wage worker, like me, you can find cheaper rents further away – but that usually requires a car – which leaves you financially worse off than where you started, often means living in a lifeless suburb, and means wasting more of your time sitting in traffic.

I’m car-free because it’s like getting a $1200 bonus that allows me to live in a more expensive but culturally vibrant neighborhood where I can easily walk, bike, and take the bus to great restaurants and cultural amenities. My commute to work is six minutes on a bicycle. The more bike infrastructure we get, the less I ride Metro. 85% of bike collisions occur where there are no bike lanes. I’ve been hit by drivers three times and each time it was where there was no bike lane.

And it’s not just about increasing Metro ridership. The percentage of Angelenos who mostly walk has increased every year since 2022 – which is thanks, in part, to densification. There’s a direct correlation with higher walking and biking rates for short trips. The percentage of Angelenos who mostly ride a bike has increased every year since 2022 – as we’ve (too) slowly but surely added bike infrastructure. At the same time, the percentage of Angelenos who mostly drive has dropped and a third of Angelenos essentially don’t drive at all. And despite its lower than peak ridership, Metro still had 311 million boardings in 2024 (an 8% increase of 2023) which made it the mass transit network that consistently ranks one of the three busiest mass transit networks in the US.

The more people who unlock the secret of car-free living, the more appealing I hope it will become… and it will become a lot more appealing if we get leaders who make cycling safer and taking Metro faster by upgrading our streets with dedicated bike and bus lanes. I assume, too, that has to be the hope of the majority of voters, who voted for the leaders who, with the exception of Bass, supported SB 79. As for why SB 79 might succeed where previous bills failed – I’m no expert in this area but I think the hope is that its mandatory, non-discretionary standards will make it much harder for local leaders to oppose than earlier efforts, which left more discretionary power in their hands. I reckon time will tell and my fingers remain crossed even when I don’t hold my breath.

…As for the bit about residential capacity loss, I think I might add a few lines about that to the piece because it would probably be helpful and comes up a lot. I will note here, though, that I understand it to refer to the residential capacity of the City of Los Angeles — not the County — which actually exceeded ten million in the 2010s (but has dropped sense).

LikeLike

As a transit rider myself, I would love to see ridership increase, and I agree that there are multiple factors causing the decline. But Metro ridership declined by 20% from 2014 to 2019, and since the pandemic still has not gotten back to 2019 levels. I also agree that Metro should shift funding from rail lines to busses. And yes, part of the reason that ridership is dropping is that low-income people can’t afford housing in the central city, but this is caused in part by bills like SB 79. The State and local government have approved numerous initiatives to streamline project approvals and grant density bonusses, but rather than producing lots of new low-cost housing, it’s led to rampant real estate speculation. In Koreatown, Hollywood, North Hollywood and elsewhere, we’ve seen gentrification drive out low-income renters.

To cite just one example, there used to be an apartment complex on the southeast corner of Yucca and Argyle in Hollywood. It was built in 1953 and contained 40 rent-stabilized units. In 2000 the LA County Assessor put the assessed value of the property at $2,345,000. Some years later, a developer submitted an application for a large mixed-use project that included a 30-story tower offering up to 269 residential units. In December 2020, the LA City Council approved the project, granting a zone change, a height district change and a density bonus. At the end of 2024, the 40 rent-stabilized units were demolished. It does not appear that LADBS has issued any permits for new construction. Today the property at Yucca and Argyle is a vacant lot. Currently the LA County Assessor puts the assessed value of the property at $14,500,000, six times its assessed value in 2000. By offering density bonusses, streamlined approvals and CEQA exemptions, elected officials are giving more power to developers and preventing communities from having a voice in planning decisions.

Economists keep saying that all we have to do is increase supply and prices will fall, but they’re still living in the 20th century. Fifty or sixty years ago, you had lots of developers building multifamily housing at a range of price levels, and the investors were often individuals or couples who were just looking for a steady source of income. This has changed dramatically. Most mom and pop landlords have either sold their buildings or passed away. The new generation of real estate investors are only thinking of maximizing the value of an asset. They don’t want to manage a building. In many cases, they’ll buy a small or mid-size building, apply for something much larger using a density bonus, and once the project is approved they’ll flip the property for a profit without building anything. There used to be 14 RSO units at 5600 Hollywood Blvd.. In 2022 the city approved an 18-story density-bonus project with 200 residential units. The RSO units were demolished a couple years ago, and the site is still a vacant lot. A decade ago there were 16 RSO units at 1739 Bronson. A developer bought the property and tore them down. In 2023 the City gave the developer a density bonus to build a 23 story tower with 129 units. It’s still a vacant lot. In the 20th century we had a competitive housing market that kept prices relatively low. In the 21st century, we have a speculative market where real estate investors are only interested in driving up the value of an asset. When we streamline approvals, offer density bonusses and make projects exempt from CEQA, we rob the tenants who used to live in these buildings of their chance to be heard. We take power away from them and hand it to investors whose only desire is to get rid of the tenants.

Lastly, to clarify, when I spoke about zoned capacity in my original comment, I was referring to the 1995 General Plan for the City of Los Angeles. I used the figure for LA County’s average household size because I couldn’t find a similar figure for the City of LA. I realize that was confusing, but I believe the EIR for the 1995 General Plan showed that the zoned capacity for the City of LA, even after Prop U, was about 8.3 million. If you can point me to another analysis with a different conclusion, I’d be happy to look at it.

I have no problem with increasing density near transit, IF it delivers results. I’m glad that more people are walking and biking, but for almost a decade both Sacramento and LA City Hall have been writing laws to promote transit-oriented density. They’ve told us repeatedly that they’re going to increase density to drive prices down and increase transit ridership. Instead, prices have continued to rise and Metro statistics show that transit ridership has been dropping steadily. (The decline actually began in 2014. While ridership is up compared to the pandemic, we’re still not back to 2019 levels.) If elected officials really want lower housing costs and higher transit ridership, they need to look at the actual data and ask why these measures aren’t working.

Like you, I would love to see a walkable, bikeable city with affordable housing near transit so that nobody needs a car. Unfortunately, eight years and 80 housing bills later, Sacramento has failed to deliver any of these things. If SB 79 does change the trend, that would be great, but given the current situation, to me it looks like more of the same.

Sorry to be so negative. I’m both disappointed and angry that our elected officials promise so much and deliver so little. I don’t mean to take it out on you. Your blog is great. I hope I’m wrong about where we’re heading.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I appreciate the feedback, honestly. That’s why I (subtly) try to cast a bit of blame in multiple directions. As a poor, working class Angeleno who will probably never NOT be poor — I often feel like housing battles are mostly waged between wealthy homeowners and ultra-wealthy developers who both try to enlist the working class majority for their side whilst neither actually does anyting in our interest. I don’t feel, though, that downzoning the city helped the poor in any way. Allowing for a return of 1920s style TODs may help and it may not, but it seems like a sane move whereas creating parking mandates that made housing unaffordable were not. I can’t help but think that removing car storage will incentivize walking and taking transit. To me, removing the barrier to civic participation that car ownership represents seems like it should be an achievable goal in any city.

LikeLike

Lived in silverlake in 90s. Hope new law will benefit all. Neat old buildings. Bring back sunset junction street fair!

LikeLiked by 1 person