It’s almost Halloween. Surely one of the greatest holidays, Halloween is up there, in my estimation, with Burns Supper, Nowruz, Thanksgiving, and Thanksgiving II. I keep reading and hearing, though, that Halloween is cancelled this year, thanks to the mismanagement at nearly every level of the COVID-19 pandemic. Surely you can’t cancel a holiday, though, especially one in which the boundary between our world and the Otherworld opens through which fairies and dead souls will pass back and forth at will. And thus, 31 October will be Halloween… and the next day, Día de los Muertos.

Of course, when people say that Halloween is cancelled, they actually mean that Halloween — as they are used to celebrating it — is not happening. In other words, trick-or-treating and house parties are cancelled. I hope that people won’t but know that there will be Halloween super-spreading events. I guess trick-or-treating isn’t probably happening as much because that tends to require broad community support… but then, I had trick-or-treaters in at least a decade. Back when my peers started having kids, a cold war was seemingly waged between parents and children over who Halloween was for… and when I see kids corralled at “block parties” while their parents groove to cover acts performing songs from the Jack FM canon I think I know the answer. In fact, today, Halloween is ranked the second-biggest “commercial holiday” after Christmas — which is just sad.

I feel like Halloween’s been on a moribund course for some time. When my generation were kids, you see, adults who should’ve known better filled our heads with nonsense about poisoned cookies and razor blades hidden in apples by devil-worshiping metal fans. Consequently, it was agreed on by all sensible people that caramel apples and cookies were out and that the only way to ensure a safe Halloween was by purchasing mass-produced garbage candy made by either a multinational corporation. That mass-produced American chocolate tastes like barf actually prepared us for a future in which plastic trick-or-treat jack o’ lanterns would be traded for red plastic Solo cups full of mass-produced beer. Gen Xers refused to stop dressing up on Halloween — although costumes are inevitably sexed-up — and thus we find ourselves in an age in which people my age dress as sexy/slutty coronavirus, bottles of sriracha, or characters from whatever overrated Netflix show we’re binge-watching while their kids are subjected to covers of Journey and White Stripes songs.

I still love Halloween, though, and to be honest, I’ll probably observe this one like I do most: probably watch a horror film or thriller, listen to a bit of music, eat some soul cakes, drink some mulled wine, and go for an evening stroll. At some point I’ll probably stress about all of the things I’ve left out of this essay. Hopefully, another glass of mulled wine will help me let it go.

https://www.google.com/maps/d/embed?mid=1HkanVKu57cgk_v6x96Bpw6p7XyGztDAM

Anyway, I hope you get some enjoyment out of this piece, have a happy and safe Halloween, and find happiness in the year’s dark half.

🎃 ❦ 🎃

We all know what Halloween is but what, really, is Gothic? In its earliest sense, “Gothic” referred to an ancient Germanic people (known, in their own alphabet as “𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰” in their own language). The original Goths, of course, had no more knowledge of Southern California than its people did of Germanic Europe.

In the Middle Ages, Gothic came to refer to an art and architecture movement that emerged out of the Romanesque tradition and spread across Europe. There are quite a few fine examples of Gothic Revival architecture in Los Angeles — and, perhaps more interestingly — of architecture that combines elements of it with other styles. Still, I doubt that anyone’s ever moved to Los Angeles out of a love of Gothic architecture. On the other hand, there are most certainly Europeans who’ve fled its tyranny. British radio host and author Frances Anderton has spoken on several occasions about moving to Los Angeles, in part at least, to get away from the Gothic cityscape of her hometown of Bath. I’ve included some Gothic buildings on this map of Gothic (in the broadest sense) Los Angeles — in part because it’s hard not to think of them not just as Gothic but as spooky.

If there’s another architectural era widely regarded as spooky, it has to be the Victorian. I doubt the architects of brightly colored “painted ladies” meant for the mansions they designed to be frightful but if someone imagines a haunted house, there’s a good bet that it’s Victorian. The Victorian era ended in 1901 — but by the 1920s, Victorian era homes were the settings for a genre of quasi-horror film, the so-called “old dark house” thriller. In Los Angeles, many Angelenos flock to Angeleno Heights around Halloween. Michael’s house from the video for Michael Jackson‘s “Thriller” video is located there. Heritage Square, a living history museum, also serves up spooky vibes and every year there are Halloween events. This year they’re having a Halloween Night Picnic. With the pandemic, many annual Halloween events have either gone car-dependent or online. Personally, I’d rather go for a walk to some haunted spot or to admire some architecture than drive anywhere. Any time I use a car in a city, I feel a profound sense that I’ve failed.

Gothic, in the sense with which I’m using it here, began as a literary movement in 18th century England, with the publication of works like Horace Walpole‘s The Castle of Otranto (1764), Clara Reeve‘s The Old English Baron (1778), and Matthew Gregory Lewis‘s The Monk (1796). With the development of the larger Romantic movement, Gothic literature really took off with the publication of works like Mary Shelley‘s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), Bram Stoker‘s Dracula (1897), and pretty much the entire oeuvre of Edgar Allan Poe. Earlier this month I read Washington Irving‘s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” for the first time and it was completely appropriate for the season. Now I’m reading Emily Brontë‘s Wuthering Heights which — although so far lacks any supernatural elements, certainly strikes me as Gothic and also goes well with our pleasantly gloomy weather of late. Los Angeles, though, does not have a tradition of Gothic literature, as far as I know. I guess the closest I’ve come to reading a Gothic Los Angeles novel was, perhaps, the novelization of the film Halloween II that my brother bought for me when I was a kid. It might be a stretch to refer to it as a Los Angeles novel (or even a novel, for that matter), but the houses that played those of Michael Myers and Laurie Strode (the principals in the Halloween franchise) are both located in South Pasadena, not Haddonfield, Illinois.

📚 ❦ 📚

Los Angeles’s first people, the Chumash, have loads of stories that are somewhat Gothic — filled, as they are, of malevolent spirits, magic, shape-shifters, death, and monsters. I’m less familiar with the myths and legends of the Tongva, who arrive more recently but where the dominant Native American people at the time of the Spanish Conquest, but they almost certainly had their Gothic side as well, as did their conquerors, who, of course, celebrated Día de Muertos. There is disagreement amongst Mexican academics over whether or not the holiday has pre-Hispanic roots but whatever the case may be, it’s very popular in Mexico and Los Angeles (which was part of Mexico from 1810-1848).

🐬 ❦ 🐺

LOS ANGELES OCCULT

There isn’t much that strikes me as Gothic about 18th century Los Angeles. Genocide and conquest are too real and sadly, too mundane to qualify as Gothic. When the century drew to a close, there were just 315 people living in the tiny pueblo — although I’m sure they, like most people, shared ghost stories and recounted supernatural experiences.

Jumping ahead to the late 19th century, there were numerous sects of Spiritualists — a faith whose adherents communicated with the spirits of the dead — but they were as much proto-hippies as goths — and the spirits with whom they communed usually advised them to embrace gender equality, free love, and veganism. They had a surprisingly long run, though. Madame Edith Maida Lessing presided over a love cult in Glassell Park‘s Mount Helios in the 1920s. Los Angeles has long exerted an attraction on dreamers, seekers, and the open-minded — and sometimes, those willing to exploit them. No matter how benevolent they might, in fact, be — new religions, secret societies, and cults are all a bit eerie to me and Los Angeles has given birth to quite a few that are still active, including the Aetherius Society, the Builders Of The Adytum, the Church of Scientology, the Clandestine Order of Illuminated Gentlemen, the Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness, Pentecostalism, the Philosophical Research Society, the Self-Realization Fellowship, the Theosophical Society Pasadena, the United Lodge of Theosophists, and, no doubt, more.

🔮 ❦ 🔮

HOUDINI

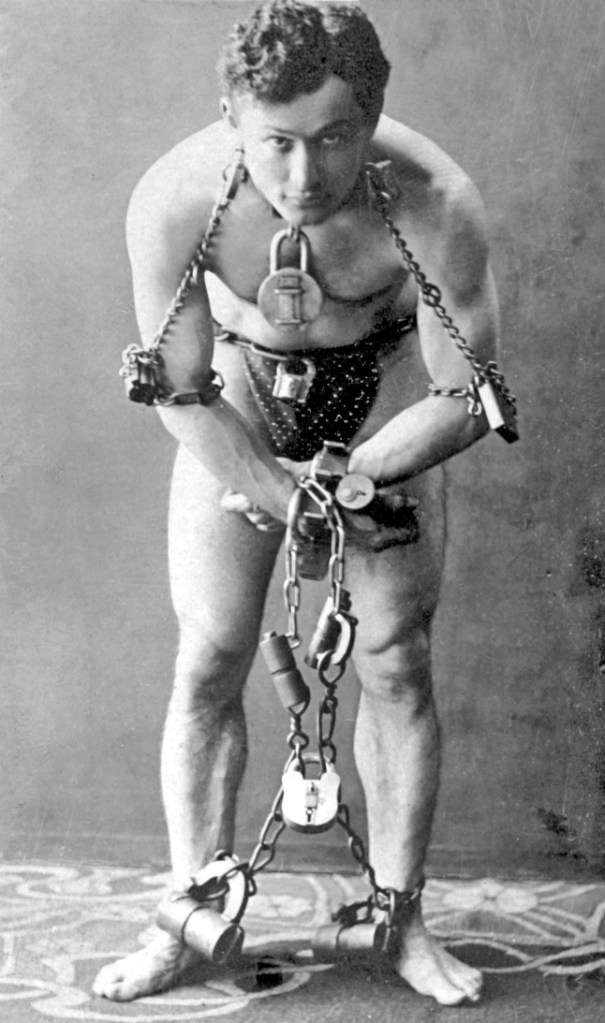

One man who it may come as a surprise to learn was very anti-Spiritualist was the most famous magician of all time, Harry Houdini. Houdini was born Erik Weisz in Hungary in 1874. Houdini’s first taste of fame as an escape artist came during his stint in Vaudeville, where he was billed as Harry ‘Handcuff’ Houdini as he specialized in freeing himself from chains, shackles, sealed containers, graves, and more.

McManus-Young Collection – Library of Congress

He was also the scourge of Spiritualists and other mediums. As a member of the Scientific American committee, he offered a cash prize to any medium who could successfully demonstrate their supernatural abilities. Not surprisingly, no medium ever collected any money from the society. Houdini even co-authored a book about exposing mediums titled A Magician Among the Spirits — also the name of an underrated album by the Church.

Houdini also starred in several films, which weren’t especially successful — perhaps because studio trickery rendered cinematic magic tricks less impressive than seeing it performed in real life. In 1919, though, whilst pursuing his cinematic career, he moved to to a house owned by Ralph M. Walker in the Laurel Canyon neighborhood where he and his wife, Bess, likely stayed in the no-longer-extant guesthouse whilst the magician filmed The Grim Game and Terror Island.

Despite his disbelief in Spiritualism, Houdini nevertheless made an agreement with Bess that if he found a way to contact her from beyond the grave, he would communicate the message, “Rosabelle believe!” Houdini died in Detroit of peritonitis, secondary to a ruptured appendix, not long after — in 1926. For ten years afterward, Bess dutifully but fruitlessly conducted séances on Halloween. Bess died of a heart attack in 1943.

🕴️ ❦ 🕴️

THE LADY IS A VAMP

While Los Angeles has never been associated with Gothic literature, it did have a profound role in the development of the horror film. The first motion picture was made, in Europe, in 1888. By 1896, there were films with ghosts. Werewolves and vampires showed up not long after. Before there were vampires, though, there were vamps — and although the first vamp film was made in New Jersey, they soon after flowered, as did American cinema, in Los Angeles.

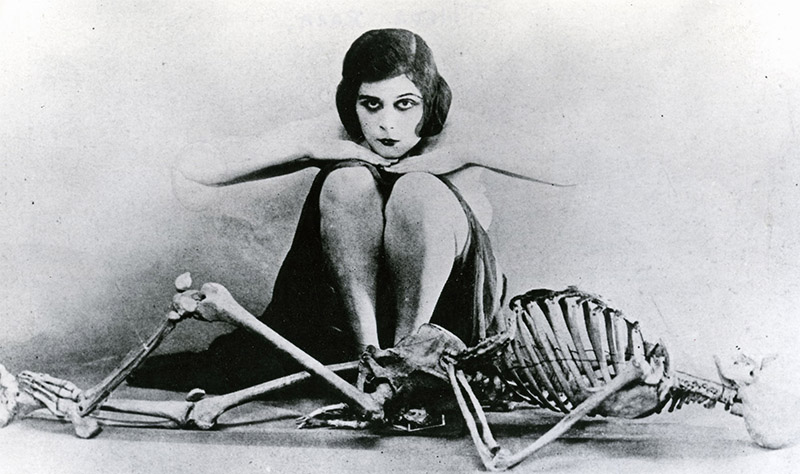

Vamps were not literally vampires but rather vampires in the metaphorical sense — a sort of femme fatale (usually “exotic”) who seemed to feed off the degradation of decent men and were thus, instrumental in the formation of horror as a film genre. Vamps usually bore a scandalous amount of skin — and darkened their eyes with copious amounts of kohl. The vamp was inspired by Pre-Raphaelites, Gothic literature, and Romantic poetry but made its biggest impression in film.

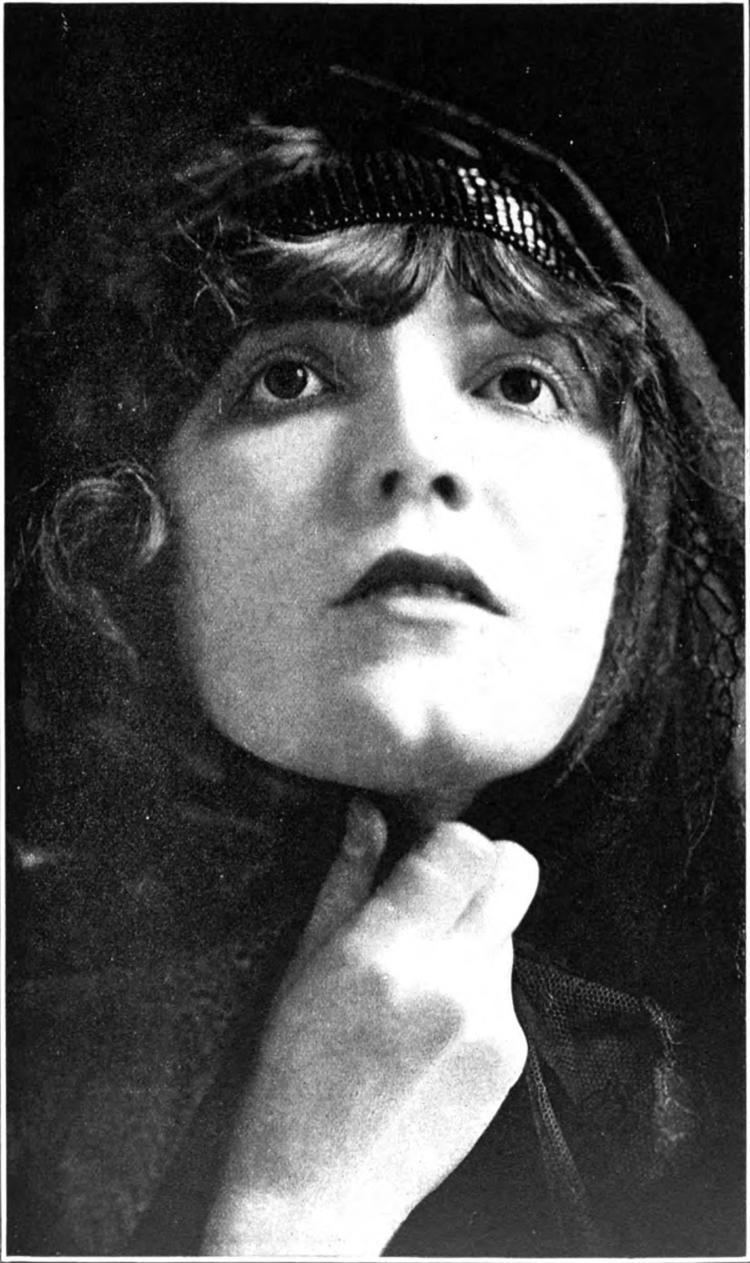

The earliest “vamp” film, 1913’s The Vampire starred Alice Hollister and was filmed in Cliffside Park, New Jersey. It has to be said that “Alice Hollister” is not the sort of exotic name befitting a vamp — but neither was it the actress’s real name. Her birth name, in fact, was Rosalie Alice Amélie Berger — but Hollister’s career began in the pre-vamp era, when American audiences preferred their actresses to be “all-American.” Hollister’s first role as a vamp was in 1913’s The Vampire. She again played a vamp the following year, in 1914’s The Vampire’s Trail. After acting in at least 90 silent films, film’s first vamp retired and moved with her husband to Costa Mesa, where she remained until her death in 1973.

No actress is more associated with the vamp than Theda Bara. Her first vamp role was in 1915’s A Fool There Was. It was her second film but her first as Theda Bara — a suitably spooky anagram of “Arab Death.” Then as now, studios were in the habit of fictionalizing stories about their stars and Fox claimed that Bara was born to an Arab sheik and French woman who raised her in the shadow of the Sphinx. In actuality, Bara was a Swiss Jew named Theodosia Burr Goodman who was born and raised in Cincinnati. She moved to Los Angeles in 1917 to star in Cleopatra. Bara made more than forty films and is generally regarded as having been Hollywood’s first female sex symbols (the first sex symbol by, most accounts, was Sessue Hayakawa). She married Scouse director and screenwriter Charles Brabin in 1921 and afterward made two more feature films before retiring in 1926. Bara died in Los Angeles in 1955.

There were numerous other actresses who specialized and vamps and who, like Hollister and Bara, made their homes in Metro Los Angeles. Barbara La Marr settled in Altadena. Estelle Taylor (While New York Sleeps) moved to Los Feliz. Hedda Hopper played several vamps before gaining notoriety as a Beverly Hills-based gossip columnist. Montana-born Myrna Loy moved to Culver City where she got her start with vamp roles. Polish actress Pola Negri (née Apolonia Chalupec) moved to Bel Air. St. Louis-born Rosemary Theby (The Great Love) moved to Whitley Heights. Amsterdam-born Jetta Goudal and Baltimore-born Louise Glaum (The Toast of Death) also moved to Los Angeles.

🧛♀️ ❦ 🧛♀️

GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM IN THE LAND OF SUNSHINE

Expressionism was an art movement that originated in Germany. It first emerged in the early 20th century in the fields of poetry and painting. Rather than striving for realistic depictions of physical reality, expressionists sought to to express emotions and ideas through radically distorted and subjective perspectives. Expressionism later spread to architecture, dance, music, theater, and film — all of which flourished during the Weimar Republic and famously drove the Nazis mad. English post-punk band Bauhaus later used a still from the expressionist film, Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari to promote their debut single, “Bela Lugosi’s Dead.” Although there were notable West Coast expressionist artists like Rico Lebrun (who lived in California for a time) and Harry Sternberg (who moved from New York City to Escondido), most American expressionist painters lived and worked in the Northeast — in particular New York City.

Many German Expressionist filmmakers, however, did move to Los Angeles, where their shadowy visions often morphed into film noir and horror. F. W. Murnau (Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens, Der letzte Mann, and Faust) moved to Los Angeles in 1926. Fritz Lang (Der Müde Tod, Die Spinnen, Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, Metropolis, and M) moved to Los Angeles in 1934. Their cinematic influence was evident in the classic works of Tod Browning and James Whale and as well as classic 1930s Universal horror films like Dracula, Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde, The Mummy, Freaks, The Invisible Man, Bride of Frankenstein, and others.

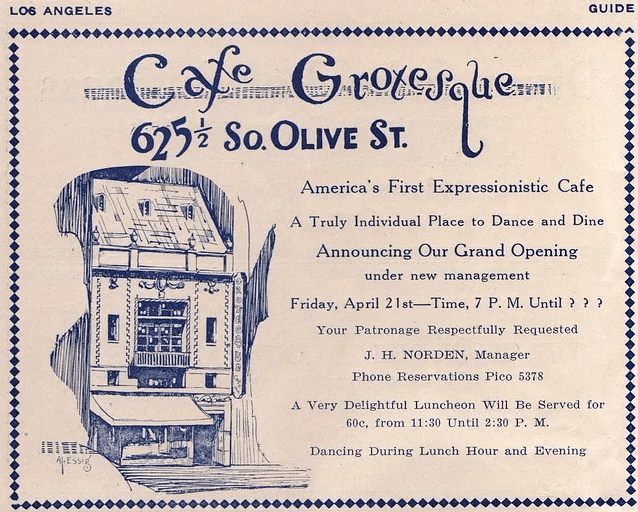

A more obscure and unexpected Los Angeles byproduct of Expressionism was a Downtown Los Angeles restaurant which billed itself as “America’s first Expressionist Café.” Little is recorded about Café Grotesque. According to an article in the Los Angeles Evening Express, then-new owner, restaurateur, and hotelier John H. Norden reopened

the restaurant on 21 April 1922. What made it expressionist, I can’t rightly say. An advertisement promises a “very delightful luncheon,” which sounds neither grotesque nor expressionist. There’s a film that was perhaps at least partly filmed at Café Grotesque — 1923’s Three O’Clock in the Morning. That film, unfortunately lost, concerned a young woman who becomes a dancer at a place called Café Grotesque. Reviewers of the day unfailingly mention its “mirror mosaic” — whatever that means. The film’s setting was New York City but as any Angeleno can tell you, that doesn’t mean it wasn’t filmed in Los Angeles.

😱 ❦ 😱

NAZIMOVA

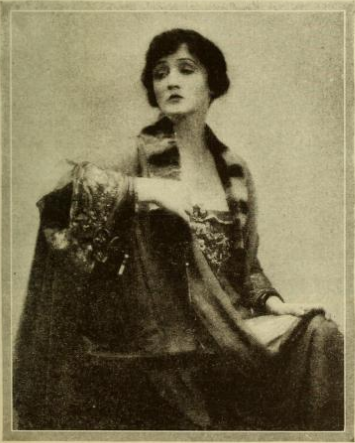

Although influenced by expressionism, Alla Nazimova, belonged more strongly to the older tradition of the Decadent movement, which arose in Western Europe in the mid-19th century with exemplars including Félicien Rops, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Théophile Gautier, and Charles Baudelaire. The Decadents promoted the artificial over the natural and excess over moderation. Decadent works were characterized by disgust with society and delight in moral and spiritual perversion. British poet and critic Arthur Symons described Decadence as “a new and beautiful and interesting disease.” One of the exemplary works of Decadence was Irish poet, philosopher, and playwright Oscar Wilde‘s 1891 play, Salomé, which Nazimova adapted into a film that also drew heavily upon the illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley.

Nazimova, herself was a product of late 19th century Eastern Europe, having been born Марем-Идес Левентон in Crimea around 1879. She wasn’t only inspired by the Decadents and in Russia, she’d become a huge star of the stage by the early 1900s performing works by the likes of Russian dramatists Anton Chekhov, Ivan Turgenev, and others.

In 1905, she and her then-boyfriend moved to New York City where she garnered acclaim in performances of plays by Russians, Norwegian modernist, Henrik Ibsen, and others. In 1912, Nazimova entered into a “lavender marriage” with gay filmmaker, Charles Bryant. She made the transition to film actor with 1916’s War Brides. In 1922, although Bryant was credited, Nazimova directed a film version of Wilde’s Decadent play, Salomé. She also starred in the title role, wrote the screenplay, and produced the film. Several of the female parts were played by men in drag. With its morbid themes of incest, sadism, and necrophilia, perhaps it should’ve come as no surprise that no Hollywood studios were interested in releasing it. Nazimova thus released it independently. It was not a box office hit, either, and reportedly bankrupted Nazimova Productions.

Bryant subsequently retired from film and dissolved his marriage with Nazimova and married (and later divorced) another woman, Marjorie Gilhooley, in 1925. In 1919, Nazimova had bought a home, nicknamed the Garden of Alla. In order to make a bit of money, she developed it into the famed Garden of Alla Hotel (later, the Garden of Allah Hotel). She lived there with her lover, Glesca Marshall from 1929 until her death in 1945.

🌕 ❦ 🌕

UNIVERSAL HORROR

No major Hollywood studio is more closely associated with horror films than Universal. Universal Film Manufacturing Company was founded in New York City in 1912 but, like many film studios, moved to Los Angeles’s Edendale neighborhood before the end of the year. By the 1920s, Lon Chaney was the studio’s chief draw and Chaney vehicles like The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925) helped establish Universal as the leading horror studio.

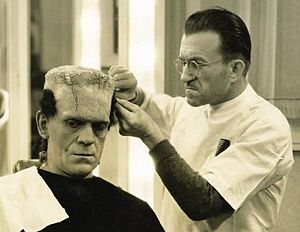

The Man Who Laughs (1928), directed by the German Expressionist filmmaker Paul Leni, was followed by expressionist-indebted horror films like Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931) (and George Melford‘s Spanish language version, filmed at the same time), James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931), Karl Freund‘s The Mummy (1932), R. C. Sherriff‘s The Invisible Man (1933), Stuart Walker‘s Werewolf of London (1935), George Waggner‘s The Wolf Man (1941), Jack Arnold‘s Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), and their many sequels and remakes. Those films made icons of actors like Bela Lugosi, Boris Karloff, and Lon Chaney Jr — as well as the monsters which they played — namely Dracula, Frankenstein, the Mummy, and the Wolf Man. The look of Universal’s “creatures” was largely the work of make-up artist and Greek immigrant Jack Pierce (né Janus Piccoula), who created the make-up for The Man Who Laughs, Dracula, Frankenstein, White Zombie, Black Cat, Werewolf of London, The Mummy, The Wolfman, and many others).

🧛 ❦ 🧛

SAMSON DE BRIER

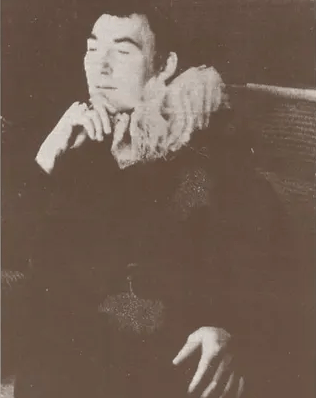

While Universal’s monsters may’ve been household names, there was, around the same time, an avant-garde underground populated by less-widely-recognized figures of an occult, gothic nature. One such figure was a self-described warlock known to his friends as Samson De Brier — or “La Perversa.”

De Brier claimed to have been born in China in 1909 and raised in Atlantic City but evidence suggests that he was, in fact, born in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1899. De Brier also claimed to have lived in Paris where he claimed that he was a lover of André Gide. In fact, however, he probably spent most of his youth in the San Francisco Bay area, where he appeared, under the equally unlikely name of “Arthur Jasmine,” in 22 films between 1915 and 1925 for the Essany studio — including notably Nazimova’s Salomé.

“Jasmine” permanently relocated to Los Angeles in 1941. According to several sources, Arthur Jasmine “died” in 1954 but in reality, he seems to have been reborn as Samson De Brier. From the 1950s through the early ’70s, De Brier hosted a popular salon at his home at in Hollywood. Guests reportedly included the likes of Anaïs Nin, Anton LaVey, Cameron, Curtis Harrington, Dennis Hopper, Jack Nicholson, Jack Parsons, James Dean, Kenneth Anger, Marlon Brando, Richard Burton, Sally Kellerman, Steve McQueen, Vampira, and others. Many were said to have been impressed by both his knowledge of occult esoterica as well as his collection of movie memorabilia. De Brier died in 1995 and wasn’t apparently, reborn as anyone.

👸 ❦ 👸

JACK PARSONS

One of De Brier’s frequent salon guests, Jack Parsons, was a noted rocket engineer, chemist, and occultist. Jack Parsons was born Marvel Whiteside Parsons, in Pasadena in 1914. As a young man, his interest in science-fiction developed into an interest in rocketry. In 1934, he co-founded the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory Rocket Research Group, which evolved into the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Parsons was also interested in the occult and, in 1941, joined the Agape Lodge, the California branch of Aleister Crowley‘s Thelemite Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO).

In 1942, Parsons became the OTO’s leader. In 1944, Parsons was expelled from JPL and the Aerojet Engineering Corporation (which he’d also co-founded). In 1945, he and his wife, Helen, separated after he had an affair with her sister, Sara, who in turn left him for Scientology-founder L. Ron Hubbard. Parsons conducted a series of sex magic rituals called Babalon Working, the goal of which was to invoke a new lover, the Thelemic goddess, Babalon. Parsons believed that his ritual had worked when he met a woman named Cameron. The two remained together until 1952, when Parsons blew himself apart in a laboratory explosion.

🚀 ❦ 🚀

CAMERON

Cameron was born Marjorie Cameron Kimmel in Belle Plain, Iowa in 1922. Sometime after World War II, she moved to Pasadena where she met Jack Parsons, who believed her to be an “elemental” woman that he’d summoned through sex magic rituals. After Parsons’s death at their home in 1952, Cameron suspected that he’d been assassinated and she attempted to contact his spirit. She later moved to Beaumont where she started a sex magic occult group known as The Children, which aimed to produce mixed-race moon children devoted to the Egyptian god, Horus. Sadly unsuccessful, the group dissolved, and Cameron befriended Samson De Brier, Curtis Harrington, and Kenneth Anger. She appeared in films by the latter two, wrote poetry, made art, and pursued her interest in esotericism from her bungalow in West Hollywood until her death there in 1995. In 2014, MOCA had an excellent Cameron exhibit called Cameron: Songs for the Witch Woman.

CURTIS HARRINGTON

Gene Curtis Harrington — friend of Samson De Brier and Cameron — was born in Los Angeles in 1926 and grew up in Beaumont. He attended school at Occidental, USC, and UCLA, the latter from which he graduated with a degree in film studies. After beginning his career as a film critic, he began making experimental films, where he would make his biggest mark. He met Kenneth Anger at Clara Grossman‘s regular silent film screenings and introduced him to the work of Aleister Crowley. The two formed Creative Film Associates which distributed experimental films by John and James Whitney, Maya Deren, and others. Harrington made two films that starred Cameron, The Wormwood Star (1956) and Night Tide (1961). In the mid-1960s, he made two genre films for Roger Corman, Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet (1965) and Queen of Blood (1966), after which he continued to focus mostly on horror, making cult films such as Games (1967), Whoever Slew Auntie Roo? (1971), What’s the Matter with Helen? (1971), The Cat Creature (1973), Killer Bees (1974), and The Dead Don’t Die (1975). He died in 2007.

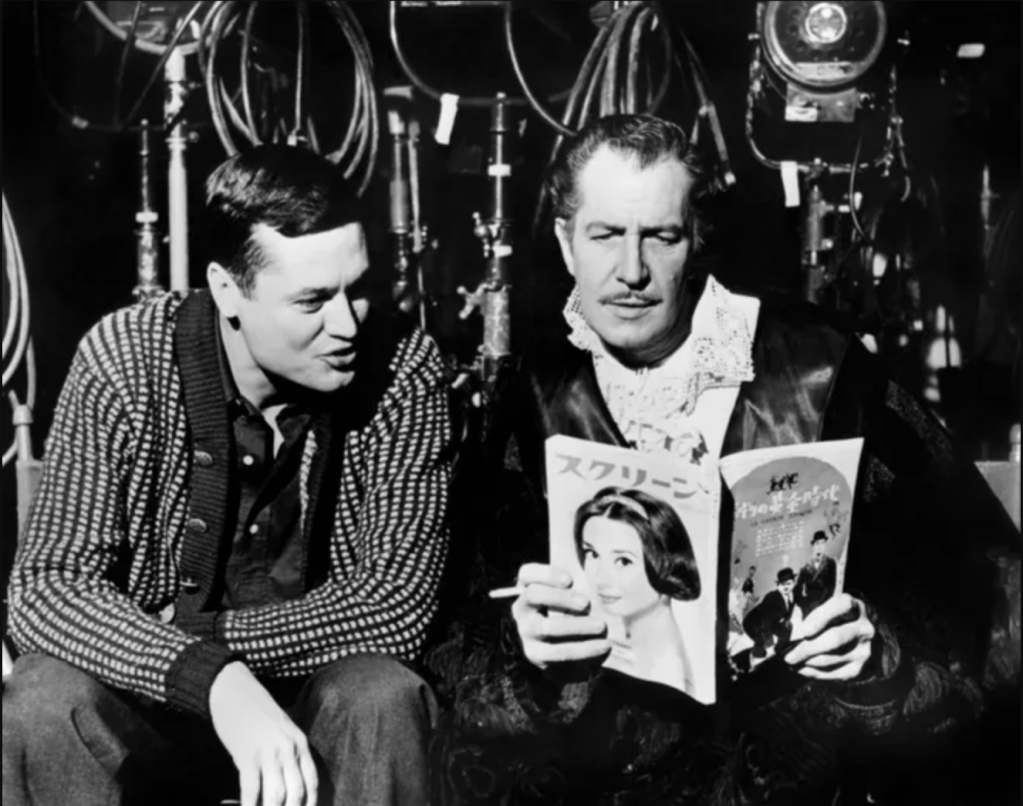

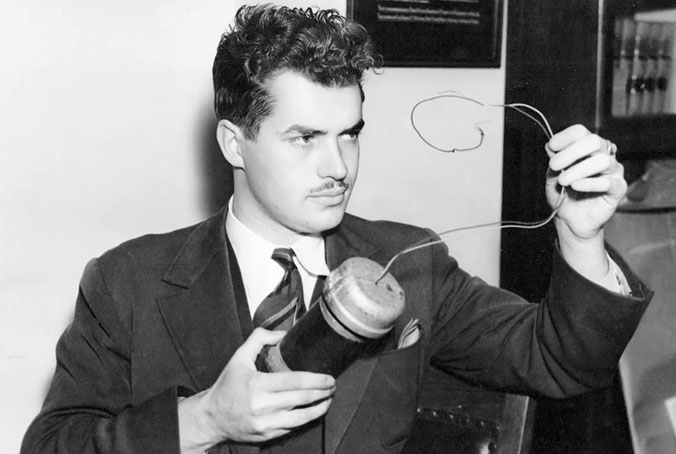

ROGER CORMAN

Roger Corman is a film director and producer known for releasing low budget, independent genre films through Allied Artists, American International Pictures, and New World Pictures. He is especially well-known for his Poe Cycle, a series of gothic horror films based upon the works of Edgar Allan Poe. He’s also known for having mentored and given many filmmakers their starts — including Francis Ford Coppola, James Cameron, Joe Dante, John Sayles, Jonathan Demme, Martin Scorsese, Monte Hellman, Paul Bartel, Peter Bogdanovich, and Ron Howard.

Roger William Corman was born in Detroit on 5 April 1926 to Anne High and William Corman. The Corman’s moved to Southern California and Roger graduated from Beverly Hills High School and, afterward, Stanford — where he studied industrial engineering. He served in the US Navy from 1944 to 1946. In 1948, back in Los Angeles, Corman was hired at US Electrical Motors on Slauson — although he quit after four days and went to 20th Century Fox where he started in the mailroom. From there, he attended Oxford where he studied English literature, followed by a stint in Paris.

Back in Los Angeles, he wrote a script called House in the Sea, made as Highway Dragnet, for Allied Artists. The following year, he produced Monster from the Ocean Floor (1954). In 1955, he directed a western, Five Guns West. His earliest horror and science-fiction efforts were The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955), Day the World Ended (1955), It Conquered the World (1956), The Undead (1957), Not of this Earth (1957), Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957), The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent (1958), War of the Satellites (1958). In 1959, Roger and his brother, Gene, formed their own production and distribution company, the Filmgroup.

In 1959, Corman made the beatnik comedy-horror film, A Bucket of Blood, foliowed by The Little Shop of Horrors (1960). Tired of churning out low budget films for AIP, Corman filmed a $200,000 budget Poe adaptation, The House of Usher, in 1960… in fifteen days. It was followed by another Poe adaptation, The Pit and the Pendulum, in 1961. The were followed by The Premature Burial (1962), Tales of Terror (1962), and The Raven (1963). X: The Man with the X-ray Eyes (1963) and The Haunted Palace (1963) followed, although neither were based on the works of Poe. The last of Corman’s Poe cycle films were The Masque of the Red Death (1964) and The Tomb of Ligeia (1965).

After a stint at Columbia, Corman returned to independent filmmaking. After directing fifty films in the 1950s and ‘60s, Corman turned his attention to producing and distributing foreign films. The Filmgroup was dissolved in 1968. Roger and Gene founded New World Pictures in 1970. Early films included bikesploitation, nursesploitation, and women-in-prison films. Corman only directed four films in the decade. By the end of the ‘70s, Corman increasingly produced movies that were inspired by Hollywood hits. Battle Beyond the Stars followed Star Wars. Alien inspired both Galaxy of Terror and Forbidden World. Corman sold New World Pictures in 1983. Corman then launched Millennium (renamed New Horizons) in 1984 and Concorde Pictures in 1985. In 1990, he directed his first film since 1978’s Deathsport, Frankenstein Unbound. It was his last directorial effort to date. As of 2023, Corman was 97 years old.

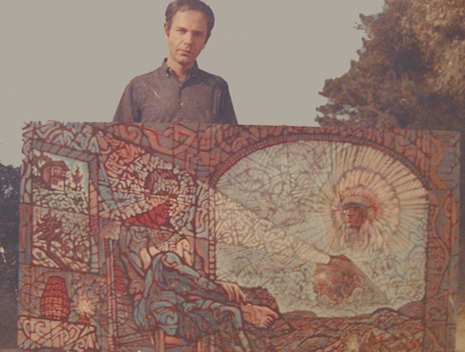

BURT SHONBERG

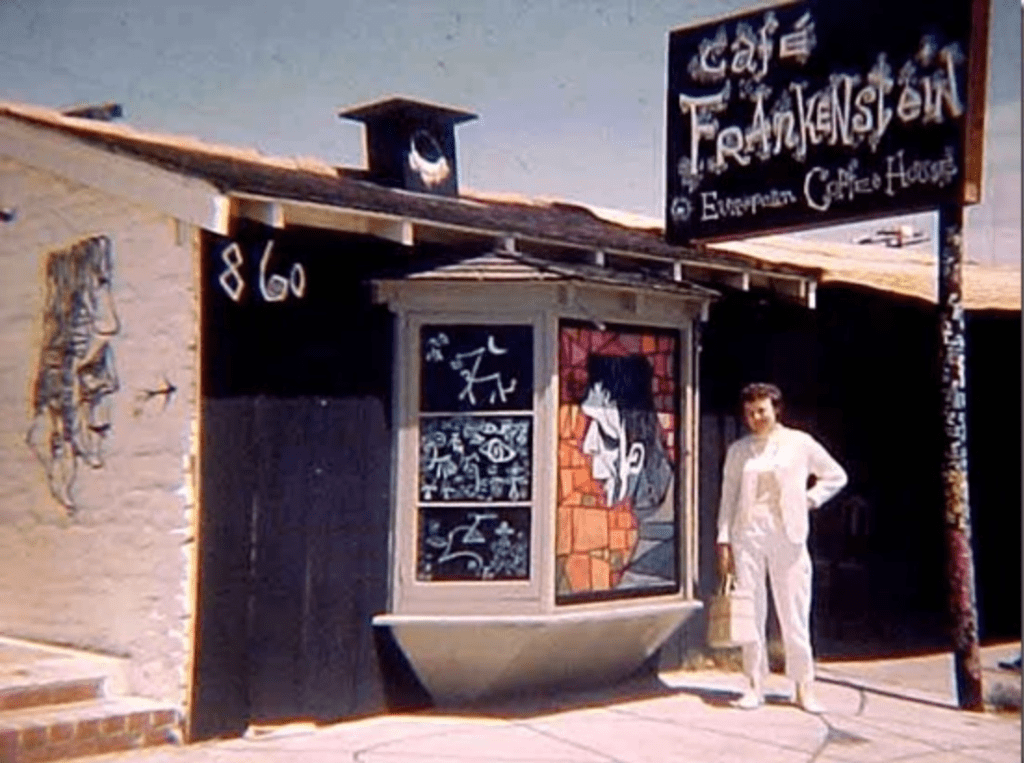

Burt Schonburg was a painter who clearly loved to paint macabre supernatural and occult subjects. His style drew on Symbolism, Decadence, Cubism, Expressionism, and Psychedelia. He was born in Revere, Massachusetts on 30 March 1933. After high school, he joined the US Army in 1950 and served for two years. There, he painted murals in the mess hall. He studied art at the Boston School of the Museum of Fine Arts. After he moved to Los Angeles, he enrolled at ArtCenter from 1953 until 1955. He painted murals at several coffeehouses, including the Bastille, Cosmo Alley, Pandora’s Box, the Purple Onion, the Seven Chefs, and Theodor Bikel’s Unicorn Cafe. He befriended Cameron, who introduced him to peyote.

In 1958, Shonberg, folk singer Doug Myres, and writer George Clayton, opened Café Frankenstein in Laguna Beach. It had its own library — that specialized in banned books. The Church League protested the cafe’s stained glass depiction of Frankenstein’s monster. Schonburg threatened to respond with a Frankenstein on the cross. They sold the cafe to Connie Vining and Michael Schley in 1960, who turned it into the 860 Club. It closed in 1962. The next owner demolished it to create car storage.

Shonberg worked as an art director on the films The Brain Eaters (1958) and Code of Silence (1960). Also in 1960, Schonberg participated in Dr. Oscar Janiger’s studies on the effects of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide 25 (LSD) on creatives at the University of California, Irvine. Naturally, Roger Corman was a fan and prominently featured his art in both The House of Usher (1960) and The Premature Burial (1962). He illustrated covers for magainze, Gamma, in 1963. He had a major solo exhibition in 1967 at Gallery Contemporary and sold much of his work. He later designed album covers for Love‘s Out Here (1969), Finnigan And Wood‘s Crazed Hipsters (1972), The Curtis Bros.’ The Curtis Bros. (1976), and Spirit‘s Spirit of ’76.

He died on 16 September 1977 at the age of 44 at his apartment in Seal Beach. He was the subject of a documentary called Out Here. His art was exhibited, for the first time in 54 years, at Cleveland’s Buckland Museum of Witchcraft and Magick and Brooklyn’s Stephen Romano Gallery.

KENNETH ANGER

Underground filmmaker Kenneth Anger (né Kenneth Wilbur Anglemyer) was born in Santa Monica in 1927. Many of his films mixed the occult and homoeroticism. His 1947 film, Fireworks, which explores sadomasochism, was the first gay narrative film produced in the US. After a stint in Europe, Anger returned to the US and continued making films. Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome was first, featuring his fellow occultists De Brier, Cameron, and Harrington. Like 1949’s Puce Moment, Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome was shot at De Brier’s Hollywood home. Later well-known films include Scorpio Rising (1964), Kustom Kar Kommandos (1965), and Lucifer Rising (1972). Anger also wrote the infamous gossip book, Hollywood Babylon (1965). His most recent film was 2013’s Airships. He died on 11 May 2023.

🎥 ❦ 🎥

It seems to me that there was a significant shift, in the 1950s, in the way that audiences responded to horror. I suppose there had always been a gleeful side to horror fandom — stretching back from burlesque reviews like Spook Scandals, to comics like The Addams Family, to the thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock, to penny dreadfuls, and even back to those pamphlets published about trials and executions of witches, warlocks, and werewolves hundreds of years ago. In the ’50s, though, there seems to me to have been a real flowering of horror culture.

The 1950s introduced the world to EC Comics‘ Tales from the Crypt and numerous other horror comics, the publication of numerous horror movie magazines, Elliott Lewis‘s Crime Classics radio program, the illustrations of Edward Gorey, a revival of classic Universal horror movies both on television and in cinemas, an explosion of B-movie monster movies both in cinemas and drive-ins, the first shock rockers, and a truly shocking number of novelty-horror pop songs.

🛸 ❦ 🛸

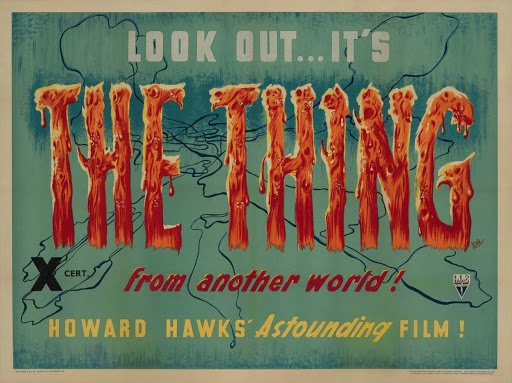

In the early 1950s, Hollywood produced several intelligent science-fiction films that included elements of horror. Some of the best were Howard Hawks‘s The Thing from Another World (1951) and Robert Wise‘s The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), both primarily in Los Angeles studios and the former notably at a Los Angeles ice storage plant in the Seafood District). They, no doubt, influenced the also excellent Forbidden Planet (1956) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) as well as drive-in fodder like Cat Women of the Moon (1953), Robot Monster (1953), Teenage Cave Man (1958), Teenage Zombies (1959), and Plan 9 from Outer Space (1957) that fail in most ways as both horror and sci-fi but succeed, when they do, as enjoyable teenage exploitation. All, too, were filmed in and around Los Angeles, in both studios and on location.

There were, occasionally, science-fiction/horror B-movies that bridged the gap between the drive-in and the cinema; films like The Fly (1958) and The Blob (1958). Quite a few, including It Came From Outer Space (1953), Tarantula! (1955), This Island Earth (1955), Creature From the Black Lagoon (1956), were made, like the classic horror of the 1930s, at Universal, in Universal City. Several were elevated not just by their talented casts and crews and relatively large budgets, but also their wonderful scores — many of which were composed by the great one of two great composers, Hans J. Salter and Herman Stein. Although not widely recognized, both are rightly regarded as the chief architects of the sound of horror and science-fiction.

🤖 ❦ 🤖

THE SOUND OF HORROR CINEMA

Hans J. Salter was born on 14 January 1896, in Lviv, Ukraine. He studied at the Vienna Academy of Music under avant-garde Expressionist composers Franz Schreker, Alban Berg, and others. After a stint with the Berlin State Opera, Salter began composing at Universum-Film Aktiengesellschaft (UFA) beginning in 1928. In 1937, Salter moved to Los Angeles where he was hired by Universal to score films, some of his notable being for films including The Wolf Man (1941), The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), Son of Dracula (1943), House of Frankenstein (1944), Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), The Mole People (1956), and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957). Salter eventually left Universal to pursue work on television. He died in 1994.

Herman Stein was born 19 August 1915 in Philadelphia. Stein was a child prodigy and made his concert debut on the piano at the age of six. He composed and arranged with jazz bands for radio programs in the 1930s and ’40s. After serving in World War II, he moved to Los Angeles in 1948 where he studied under Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco. In 1950, he married violist Anita Shervin. He was hired by Universal in 1951, where he scored science-fiction/horror films like It Came from Outer Space, Revenge of the Creature, This Island Earth, I’ve Lived Before, The Land Unknown, and The Monolith Monsters.

After scoring nearly 200 films for Universal, Stein moved to television. He also wrote for pleasure, composing pieces like “Suite for Mario” and “The Sour Suite.” He died in 2007. He and his Los Feliz home were the subject of an enjoyable episode of Bill Barol‘s podcast, HOME: Stories from L.A.

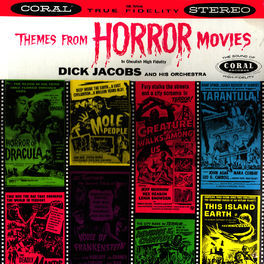

In 1959, Dick Jacobs And His Orchestra released the LP, Themes From Horror Movies, which I loved listening to as a child. It included narration by a horror host (voiced by Bob McFadden — the voice of Franken Berry). Two of the album’s fourteen themes were composed by James Bernard. Two were composed by Henry Mancini. Four were Stein compositions and another four were by Salter.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN

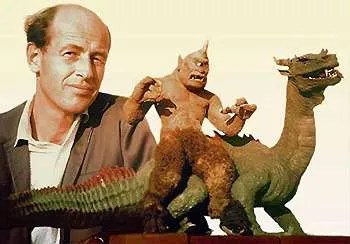

Ray Harryhausen was a special effects creator and stop motion model animator known, especially, for creating movie monsters. He was born in Los Angeles on 29 June 1920 to Frederick W. and Martha L. Harryhausen. They lived in Chesterfield Square, with young Ray experimenting with special effects in the home’s garage before opening a studio nearby, and also in Chesterfield Square.

While still in high school, he enrolled in evening classes at the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California. There he befriended science-fiction writer Ray Bradbury —a member of the Science Fiction League — who persuaded him to join in 1939. There, they befriended Forrest J. Ackerman . He studied art and anatomy at Los Angeles City College. He got his first animation job on George Pal‘s Puppetoons. During the Second World War, Harryhausen served in the US Army’s Special Services Division. He worked on the films Mighty Joe Young (1949 — with King Kong‘s Willis H. O’Brien), The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956), 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), and The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) before moving to the UK in 1960, where he continued to work in film until 1981.’s Clash of the Titans.

Harryhausen married Diana Livingstone Bruce in 1962. They had a daughter named Vanessa. The Ray & Diana Harryhausen Foundation was founded in 1986 to look after Harryhausen’s collection. The documentary, Ray Harryhausen – Special Effects Titan, was released in 2013. He died on 7 May 2013. Diana died five months later.

📺 ❦ 📺

TELEVISION HORROR

Surely one of the primary catalysts for the horror revival of the 1950s was Shock Theater (or Shock!), a collection of vintage horror films sold to television stations around the nation in 1957. Television had been around since the 1920s but it was only in the late 1940s that it was anything more than an expensive toy for a very small number of rich people. By the end of the decade, the majority of Americans had a television, and TV Guide was the most widely-circulated publication.

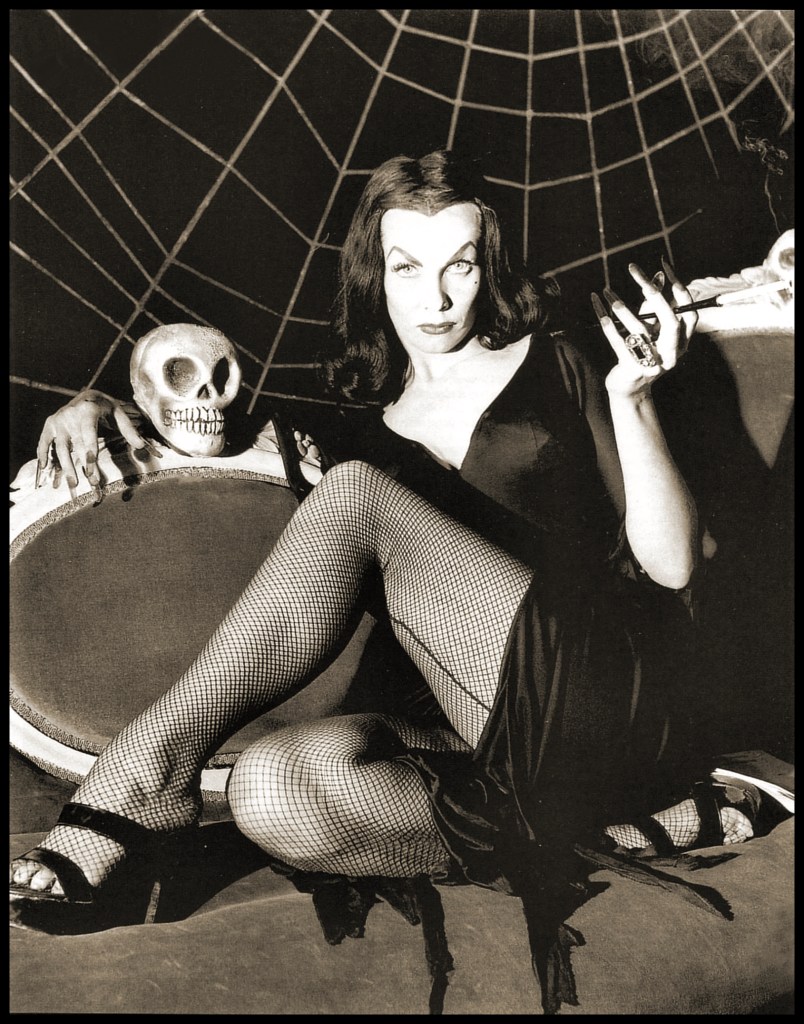

Television and the films in Shock! were primarily geared towards a youth audience. As with most local children’s programming, the films were presented by a host — albeit hosts with, in this case, a Gothic edge. Some of the best-known horror hosts were Chicago‘s Marvin, Cleveland‘s Ghoulardi, Detroit’s Sir Graves Ghastly, New Orleans‘s Morgus the Magnificent, Portland‘s Tarantula Ghoul, Philadelphia’s Roland, and most iconic of all, Los Angeles’s Vampira.

Vampira’s real name was Maila Elizabeth Syrjäniemi. She was born in 1922 and moved to Los Angeles to pursue an acting career in 1940. After two roles as an uncredited extra, she (credited as Vampira) played a “lady mortician” on a 1952 episode of the comedy series, My Hero. The look — pale skin, long black hair, tight black dress — owed an obvious debt to Morticia Addams from the comic, The Addams Family. From 1954-1955, she starred in her own show, KABC‘s The Vampira Show, which was followed by KHJ-TV‘s Vampira Returns and Vampira. In 1956, she appeared in Ed Wood‘s infamous Plan 9 From Outer Space (first screened in 1957 as Grave Robbers from Outer Space), mostly filmed in the San Fernando Valley.

In the 1960s, she opened an antique store, Vampira’s Attic, on Melrose Avenue. She was the subject of many novelty-horror songs in the 1950s and ’60s. Bobby Bare sang a song called “Vampira” in 1958. The tradition continued all the way up to a song of the same name from the Misfits in 1982. In 1987 an ’88, Vampire released two of her own singles (backed by Satan’s Cheerleaders): “I’m Damned” and “Genocide Utopia.” She died at her home in Hollywood in 2008.

Of course, television wasn’t only a medium for old films and there were notable adult-oriented horror-thriller-fantasy television series that ran in that era. Most were produced in Los Angeles — although the Roald Dahl-hosted Way Out, produced in New York, is worth seeking out. Some of the best include Out There (1951-1952), Tales of Tomorrow (1951-1953), Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-1965), Science Fiction Theatre (1955-1957), The Twilight Zone (1959-1964), the Boris Karloff-hosted Thriller (1960-1962), and The Outer Limits (1963-1965).

There were also more family-oriented monster sitcoms. Cartoonist Charles Addams‘s The Addams Family made the jump to television in 1964. The series was filmed for ABC at 1040 North Las Palmas Avenue, in Hollywood. Hot on its heels was The Munsters, filmed for at Universal Studios for CBS.

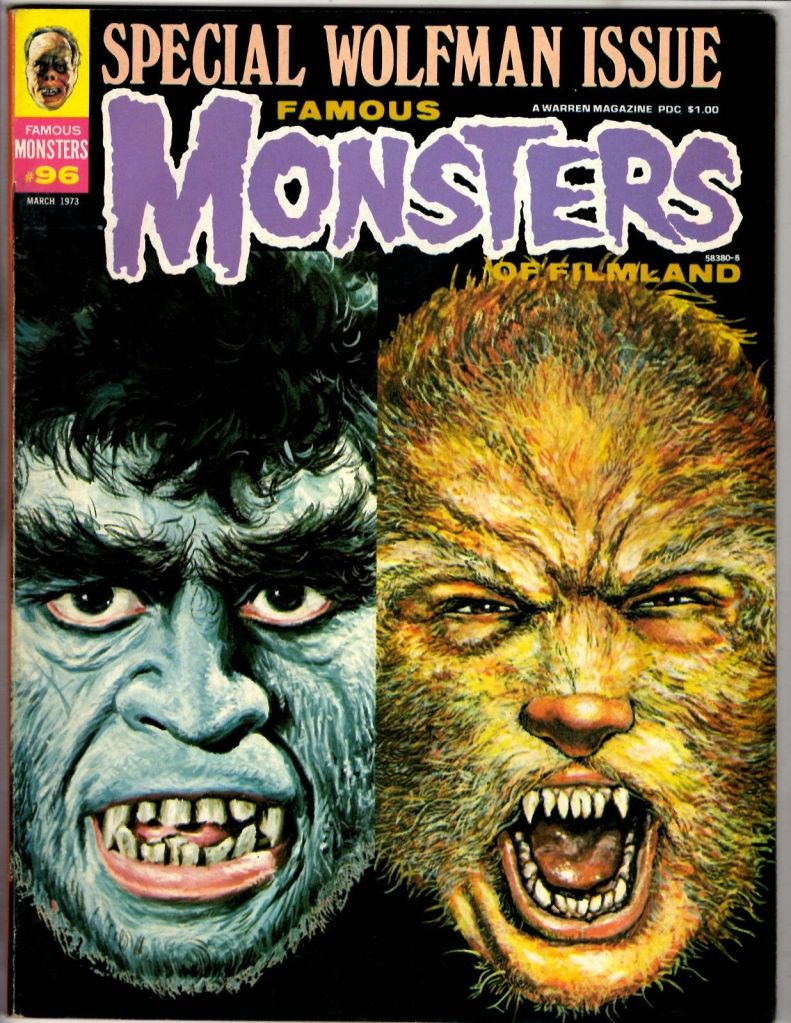

Another key ingredient of the 1950s horror explosion was the magazine, Famous Monsters of Filmland, launched by Forrest J Ackerman in 1958. Ackerman was born in Los Angeles in 1916. He later contributed to early science fiction fanzines like The Time Traveller and The Science Fiction Magazine. In 1939, he attended — in costumes designed by his girlfriend “Morojo” — the First World Science Fiction Convention in New York City. He stuffed his Los Feliz home, the Ackermansion, with a massive collection of horror and science-fiction memorabilia. Eventually, he had to expand and relocated to Son of Ackermansion. In 1961, he launched a science-fiction counterpart, Spaceman, both of which I used to thumb through the yellowing pages of as a kid. Famous Monsters of Filmland was published until 1983. Ackerman died in 2008 at the age of 92.

🏎️ ❦ 🏎️

HOT ROD MONSTERS

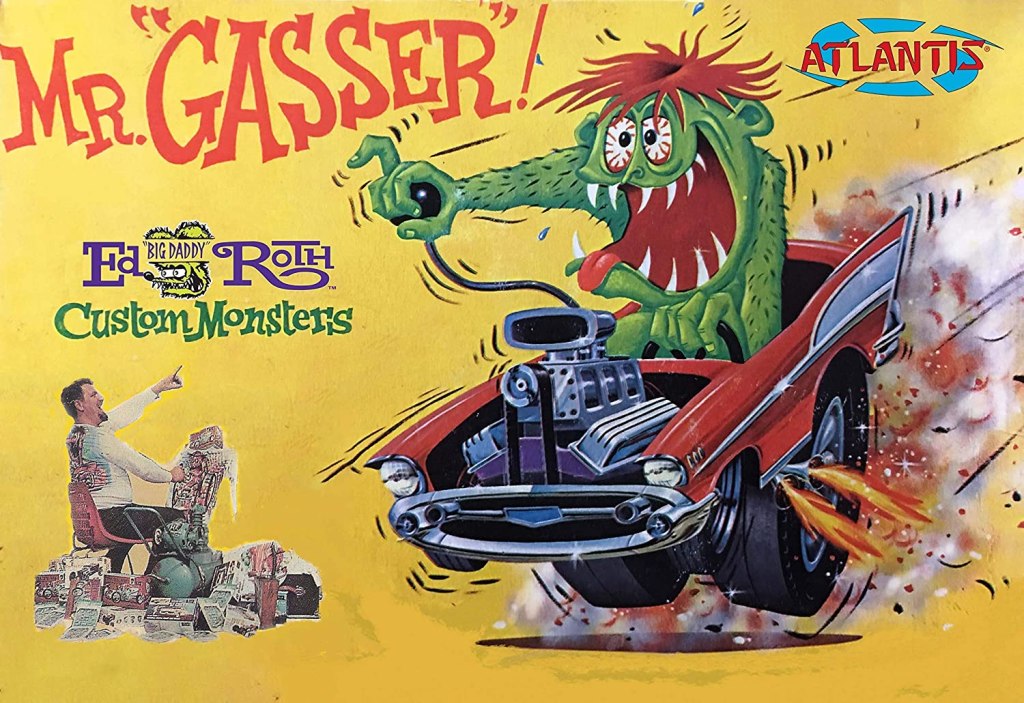

The 1950s monster movie craze and the 1950s car craze collided in Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, an artist and hotrodder. Roth was born in Beverly Hills in 1932 and grew up in the Southeast Los Angeles suburb of Bell. Roth began selling his custom “weirdo” T-shirts as early as 1958, which popularized the theme of monsters in hot rods. In 1959, Roth opened a Kustom Kulture shop in nearby Maywood.

In 1962, the Revell model company began selling plastic models of Roth’s cars and, the following year introduced a line of his monsters, including his most famous, Rat Fink, as well as Brother Rat Fink, Drag Nut, Mother’s Worry, and Mr. Gasser. In 1963 and ’64, as Mr. Gasser & The Weirdos (a collaboration with Gary Usher), Roth released a trilogy of LPs that, with songs like “Hearse with a Curse,” “Phantom Surfer,” and “Surfer Ghoul,” it could be argued, are forerunners of the Beach Goth movement that emerged in the 2010s and is now an annual party in Orange County. In 1974, Daddy Roth became a Mormon and changed his ways — although his artwork appeared on Birthday Party‘s 1982 classic, Junkyard. Roth died in Utah in 2001.

🎶 ❦ 🎶

HORROR POP

Beach Goth may’ve been invented by Mr. Gasser & the Weirdos, but horror-themed pop music goes back at least to the 1920s, when Bessie Smith released “Haunted House Blues” and Fred Sugar Hall & His Sugar Babies released “Taint No Sin (To Take Off Your Skin).” The 1930s brought songs like “Mysterious Mose,” “The Boogie Man,” “Ghost In The Graveyard,” “The Skeleton In The Closet,” “Mr. Ghost Goes To Town,” and “The Ghost of Smokey Joe.” The 1940s introduced “The Headless Horseman” and “(Ghost) Riders in the Sky: A Cowboy Legend.” The 1950s, however, saw the release of too many horror-pop songs to list individually.

The decade began fairly quietly. There was Bing Crosby & Andrews Sisters‘ “Yodelling Ghost” (1951), Louis Armstrong‘s “Spooks” (1954), and the Nu-Trends’ “Spooksville.” The visual element of novelty horror only became an issue, though, in 1956, when “Screamin’ Jay” Hawkin emerged from a coffin holding a staff topped by a smoking skull to bellow “I Put a Spell on You,” giving birth, in the process, what would later come to be known as “shock rock.” Few attempted to follow in Screamin’ Jay’s footsteps, although I’m sure Screaming Lord Sutch would’ve acknowledged his importance, as too, I suspect, would Alice Cooper, who moved to Los Angeles in 1967.

Two monster-novelty singles released in 1958, though, proved massively influential and inspired a host of songs in a similar vein. The first, “Witch Doctor,” was released in the spring of ’58 by Armenian-Angeleno Ross Bagdasarian (as Dave Seville) — which showcased the sped-up vocals that he would later use with the Chipmunks. In the summer, Sheb Wooley (the voice of the Wilhem Scream) released “Purple People Eater.” Wooley was originally from Oklahoma but moved to Los Angeles in 1950 in pursuit of work as a cowboy actor and singer.

Both goofy, gimmicky songs were huge hits and in their wake. Before the year ended, they were followed by “Bo Meets the Monster,” “Frankenstein’s Den,” “Frankenstein’s Party,” “Frankenstein Rock,” “Graveyard Rock,” “Horror Pictures,” “Janie Made a Monster,” “Morgus the Magnificent,” “The Mummy’s Bracelet,” “Vampira,” “Voodoo Voodoo,” and “Were Wolf.”

⚰️ ❦ ⚰️

Attempts to recapture the magic continued into 1959, with the release of “Batman, Wolfman, Frankenstein Or Dracula,” “Dead Man’s Stroll,” “The Headless Ghost,” “The Mummy,” “(Oooh I’m Scared) Of The Horrors Of The Black Museum,” “Rockin’ in the Graveyard,” “The Vampire,” and “The Vampires.” Several of them depicted so-called “monster parties,” a ridiculous phenomenon hilariously parodied many years later on a Mr. Show skit called “Monster Parties: Fact or Fiction.” The idea of the monster party can possibly be traced back to the calypso song, “Zombie Jamboree (Back To Back),” which Calypso Carnival Featuring King Flash recorded and released b/w “Mama, Looka Boo Boo (Boo Boo Man)” in 1956. But the proper monster party song doesn’t just depict a single type of monster throwing a party but rather a collection of various monsters temporarily setting aside their beefs to enjoy a shindig — usually in a haunted house or graveyard.

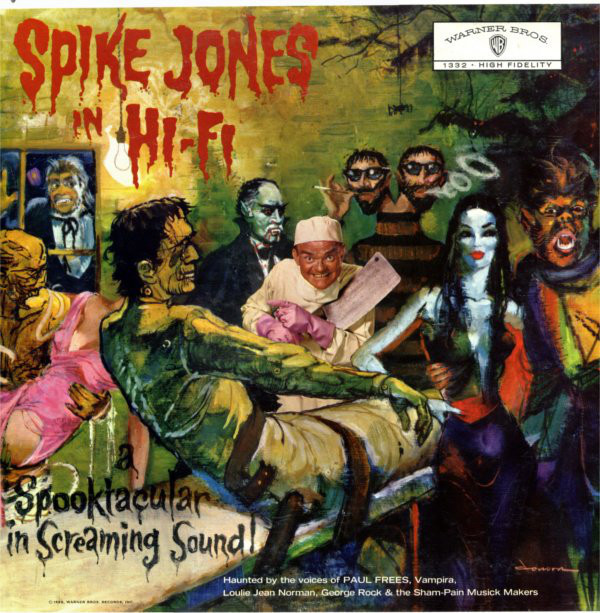

It was also in 1959 that whole LPs began to be devoted to comedy horror and related concepts. UCLA music-graduate Robert Drasnin‘s debut, Voodoo, is straight-up Exotica and not terribly dark — despite the concept and songs like “Chant Of The Moon.” Of course, Spike Jones And His Band That Plays For Fun‘s Spike Jones In Hi-Fi (A Spooktacular In Screaming Sound!) and Bob McFadden & Dor‘s Songs Our Mummy Taught Us were strictly played for laughs.

The taste for camp horror continued into the early 1960s. Brooklyn‘s Aurora Plastics Corporation launched its first monster model, “Big Franky,” in 1961, and soon after expanded into a whole line of monster models. That same year, Seaford, New York’s Nu-Cards launched a line of horror monster trading cards that paired images of movie monsters with puns and corny jokes.

The flow of monster novelty songs continued with releases like “Drac’s Back,” “I Was a Teenage Monster,” “Igor’s Lament,” “Igor’s Party,” “Jekyll and Hyde,” “The Living Dead,” “The Mummy’s Ball,” “Queen of Halloween,” “Rockin’ Zombie,” “Voodoo Woman,” “Werewolf,” and “You Can Get Him – Frankenstein” — but no one, it’s safe to say, could’ve predicted the success of 1962’s graveyard smash, “Monster Mash,” by Bobby Boris Pickett & the Crypt-Kicker 5.

Pickett had grown up on monster movies at the Somerville, Massachusetts cinema owned by his father. He later moved to Los Angeles, where in 1959 he started doing a monster-themed nightclub act and later got a job as a DJ at KRLA. In 1962, he co-wrote “Monster Mash” with Leonard Capizzi and the two shopped it around Hollywood to resounding disinterest from the major labels. It was thus released on tiny Garpax Records and quickly went on to sell a million copies and topped the singles chart for the two weeks leading up to Halloween that year.

For better or for worse, it’s the only truly inescapable Halloween song and thus it has re-entered the charts several times over the years. It was inescapable for Pickett, too, who seemed cursed by success and compelled, forever, to repeat its success with the same formula. Pickett thus released songs like “Blood Bank Blues,” “Me And My Mummy,” “Monster’s Holiday,” “Monster Man Jam,” “Monster Concert,” and “Monster Swim.” Such novelty songs were completely out of fashion by the late ’60s and when Buck Owens And The Buckaroos released “(It’s A) Monsters’ Holiday,” it surely must’ve been interpreted as an American Graffiti-esque bit of nostalgizing about a supposedly more innocent age. Nevertheless, Pickett kept at it with 1984’s “Monster Rap,” 1993’s “It’s Alive,” and finally “Climate Mash” in 2005. He died in 2007.

🏰 ❦ 🏰

Minnaert

THE MAGIC CASTLE

It was in 1963 that the Magic Castle opened in Hollywood. Before that, it was the residence of real estate investor, lawyer, banker, newspaperman, and capitalist Rollin B. Lane. The Châteauesque home was designed by Lyman Farwell and Oliver Dennis and built in 1909. After Lane died, in 1940, it was subdivided and transformed into apartments. In 1952, the Academy of Magical Arts was founded by William Larsen. He and his brother, Milt, purchased the building and incorporated their organization in 1962.

Only members of the Academy of Magical Arts and their guests are allowed entrance. To enter the building, visitors must first utter a secret phrase to a sculpture of an owl. Inside, there are numerous magic shows, historic displays, bars, and a dining room. In the music room, the Castle’s resident ghost, Irma, takes musical requests. Many famous performers have taken the stage at the castle, including Johnny Carson, Neil Patrick Harris, Orson Welles, and Steve Martin. The Magic Castle was designated a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in 1989. Although he almost certainly never visited Lane’s residence and died in the Midwest, Houdini’s ghost is said to haunt the place.

🚪 ❦ 🚪

In the early 1960s, most rock music was about girls, cars, and having a good time but something seems to have changed in the mid-1960s. President Kennedy was assassinated in 1963. The US invaded Vietnam in 1965. In 1966, Charles Whitman woke up, murdered his mother, went to school, and indiscriminately shot and killed fourteen people at the University of Texas, in a mass murder that would later inspire the 1968 film, Targets, which starred Boris Karloff as a horror actor retiring because true crime has rendered traditional horror no longer effective. Presidents had been assassinated before, the US had gone to war before, and there had been mass murders — but it was in the 1960s that one could see violence played out live on the news as they ate supper and then replayed, over and over, until they fell asleep.

GOTHIC GARAGE

A sense of menace began to creep into music, driving a stake through the heart of songs about monster parties, thanks to the garage rock scene. A group of G.I.s formed The Monks, who sang songs like “I Hate You” and “Shut Up.” Seattle‘s The Sonics sang songs like “Psycho.” Sometimes bands still evinced a taste for the Gothic, though. Over in San Jose, the Count Five sang “Psychotic Reaction” wearing matching capes, like their hero Count Dracula. In Los Angeles, a folk rock trio called the Raggamuffins morphed into the minacious Music Machine when they dawned all black clothing — including black gloves — the latter to hide the stains from the black hair dye on their hands. Of course, it wasn’t all gloom and doom in the Age of Aquarius, and television’s quasi-fictional garage band, the Monkees, weren’t exactly Gothic even as they donned Halloween costumes in an episode titled “Monkee See, Monkee Die.”

It was a garage band from Venice, the soon-to-be-famous the Doors, who were the first band to be described as “gothic rock,” which they were by critic John Stickney in 1967. The Doors were more varied and less pretentious than they’re usually given credit for — by both their fans and detractors — but they certainly had a brace full of dark, moody tunes like the Oedipal death trip, “The End,” the William Blake-quoting “End of the Night,” the dissociative “People Are Strange,” and the uncanny, Moog-driven “Strange Days.”

The Doors’ singer, Jim Morrison, married Witch Coven High Priestess Patricia Kennealy in 1970. By then, a revival of interest in the occult was almost mainstream. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, Los Angeles hosted a host of homegrown religious organizations and cults, including Cleargreen, WKFL Fountain of the World, the Manson Family, Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness, Niscience, the Source Family, and the Symbionese Liberation Army — as well as many branches of many organizations founded elsewhere.

🧙♀️ ❦ 🧙♀️

THE OCCULT GOES MAINSTREAM

Given the attitudes of the day, it may not have seemed strange, then, that Los Angeles County appointed an official witch in 1968. Louise Huebner was born in 1930 in New York City. In the 1960s, she moved to Los Angeles, where she began making regular appearances on KLAC in 1965. In 1968, Huebner was hired to help promote a series of concerts called Twelve Summer Sunday Concerts at the Hollywood Bowl. The first concert was Folklore Day, and after casting a spell, Huebner was presented with a document certifying her the Official Witch of Los Angeles County. It was stamped with the seal of the county and signed by then-Chairman of the Board of County Supervisors, Ernest Debs.

Huebner wrote books like Power through Witchcraft and recorded an album, Seduction Through Witchcraft, backed by pioneering electronic musicians Louis and Bebe Barron (who’d earlier provided the electronic score for Forbidden Planet). With titles like “The Demon Spell For Energy” and “Orgies – A Tool Of Witchcraft,” sheepish county officials insisted that Huebner stop referring to herself as the county’s official witch, insisting that the honorific title had been a joke. She refused, however, and threatened to cast a spell on the county officials if they persisted in harassing her. They relented and Huebner lived in Mount Washington, practically in the shadow of the Self-Realization Fellowship headquarters, until her death in 2014.

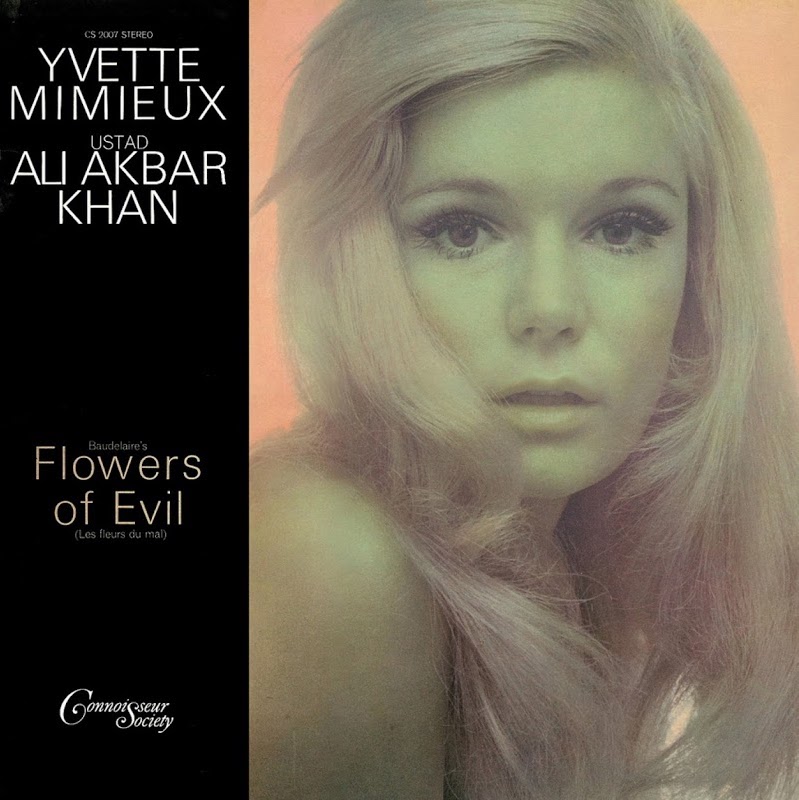

Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil (Les Fleurs du Mal) was released in 1968 by Los Angeles-born film and television actress Yvette Mimieux, who recites English translations of Baudelaire’s poetry with sensitive musical accompaniment provided by Indian Bangladeshi musician Ali Akbar Khan. It’s a strange and appealing record — a fog-shrouded bridge connecting the Decadent 1850s to the psychedelic 1960s. Mimieux was apparently frustrated with the decidedly limited roles available in Hollywood for pretty actresses and thus moved into writing — mostly journalism and short stories — but also the screenplay for 1974’s Hit Lady, in which she also starred. In 1984, she co-wrote Obsessive Love, about a stalker. The spoken word album was her only record. She died on 18 January 2022.

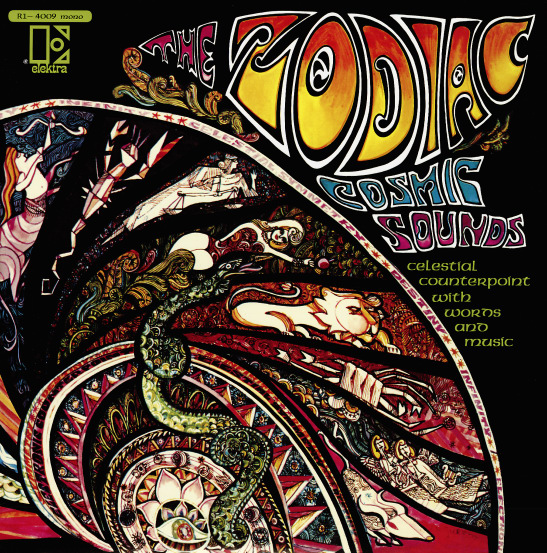

The Zodiac: Cosmic Sounds – Celestial Counterpoint with Words and Music was a concept album on the signs of the Zodiac. The music was composed by Canadian Moog pioneer Mort Garson but was performed by Paul Beaver of Beaver & Krause. The poetic narration was written by Jacques Wilson and performed by deeply-voiced Persian American singer, Cyrus Faryar. They were joined by seasoned studio musicians including Emil Richards, Carole Kaye, Hal Blaine, Bud Shank, and Mike Melvoin.

The idea was the brainchild of Jac Holzman, head of Elektra Records, who hoped to capitalize on the success of the Doors with more dark mysticism, sensing that there was a market for a darker psychedelic counterpoint to the good vibrations of flower power, the California Sound, Surf, and Sunshine Pop, for which Los Angeles was known. The album, with a dark but florid cover by Abe Gurvin, bore the instructions: Must be played in the dark. It has to be said, however, that it’s more likely to put a smile on the listener’s face than raise one’s hackles.

Holzman envisioned a series of similar concept albums and Garson composed music for the next, The Sea, but Rod McKuen dropped out and made his own concept album of that name with Anita Kerr and The San Sebastian Strings. Alex Hassilev, who produced The Zodiac, abandoned the project to make Sea Drift with The Dusk ‘Till Dawn Orchestra. Garson released twelve albums in 1969 as Signs of the Zodiac, with each album devoted to a sign. Things got decidedly spookier with his 1971 album, Black Mass, which he released under the pseudonym “Lucifer.”

😈 ❦ 😈

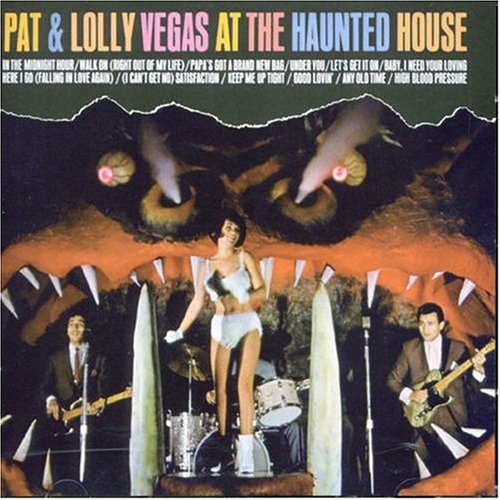

In Downtown Hollywood, there stood, in the former location of Sardi’s, a nightclub called the Haunted House. The haunted hotspot opened in 1965 and was apparently a popular location for several years. Pat & Lolly Vegas‘s live album, At the Haunted House, was recorded there and released in 1966. It was mentioned, that same year, in the liner notes of the Mothers of Invention‘s 1966 debut, Freak Out! It also appeared in films, including 1967’s It’s A Bikini World (in which Sid Haig plays an Ed Roth-like hot-rodder named “Daddy”), 1968’s Girl in Gold Boots, directed by Ted V. Mikels (The Corpse-Grinders, Blood Orgy of the She-Devils), and A Sweet Sickness, and also filmed 1968. The house drink was the Phantom (equal parts Kahlua and Arandas, a dash of rum, a splash of soda, and served on the rocks in an old-fashioned glass). It closed in 1970 and reopened, the following year, as a porn theater called the Cave.

The Haunted House may’ve only lasted five years, but Disneyland‘s Haunted Mansion has proven much more durable — outlasting long-vanished attractions like Rainbow Caverns Mine Train, Flying Saucers, Skyway, and Motor Boat Cruise. Construction of the beloved attraction began in 1962 and originally called for a less dark-dark ride. Disney, in particular, balked at the idea of anything looking rundown in his park — even a haunted house. Walt Disney died, though, in 1966 and the Haunted Mansion underwent a redesign — although not one that made it look dilapidated.

The ride finally opened in 1969 and, then as now, the Ghost Host (voiced by Paul Frees) narrated as visitors were carried along in “doom buggies.” The theme has a theme song, “Grim Grinning Ghosts,” by Buddy Baker and X Atencio. Naturally, the ride was particularly loved by Deathrockers and Goths and for its 30th anniversary in 1999, local clubs Absynthe and Release the Bats promoted and instigated the first Goth Day at the Park, an annual tradition ever since.

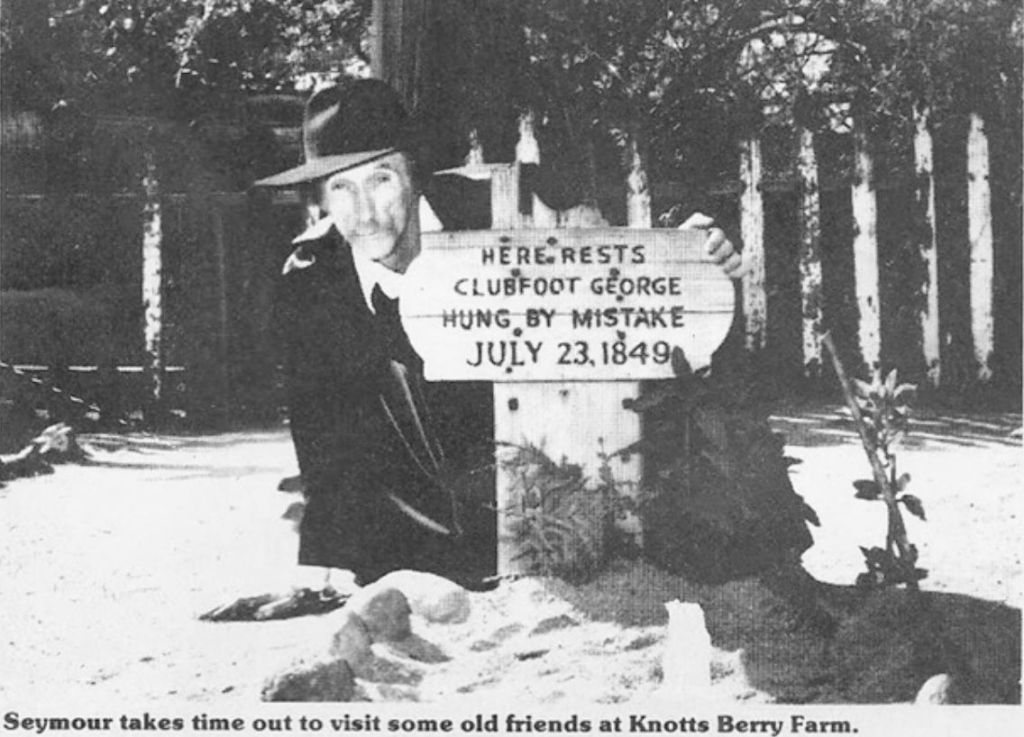

Horror spread to other amusement parks not long after. Nearby Knott’s Berry Farm launched Knott’s Scary Farm as a three-day event in October 1973. Knott’s Scary Farm’s inaugural “Ghost Host” was Larry Vincent — better known as TV’s Seymour. It’s grown and taken place every year since, except during the COVID19 pandemic, making it the first, largest, and longest-running Halloween event to be held at an amusement park. There’s also Six Flags Magic Mountain Fright Fest and Halloween Horror Nights at Universal Studios.

🎢 ❦ 🎢

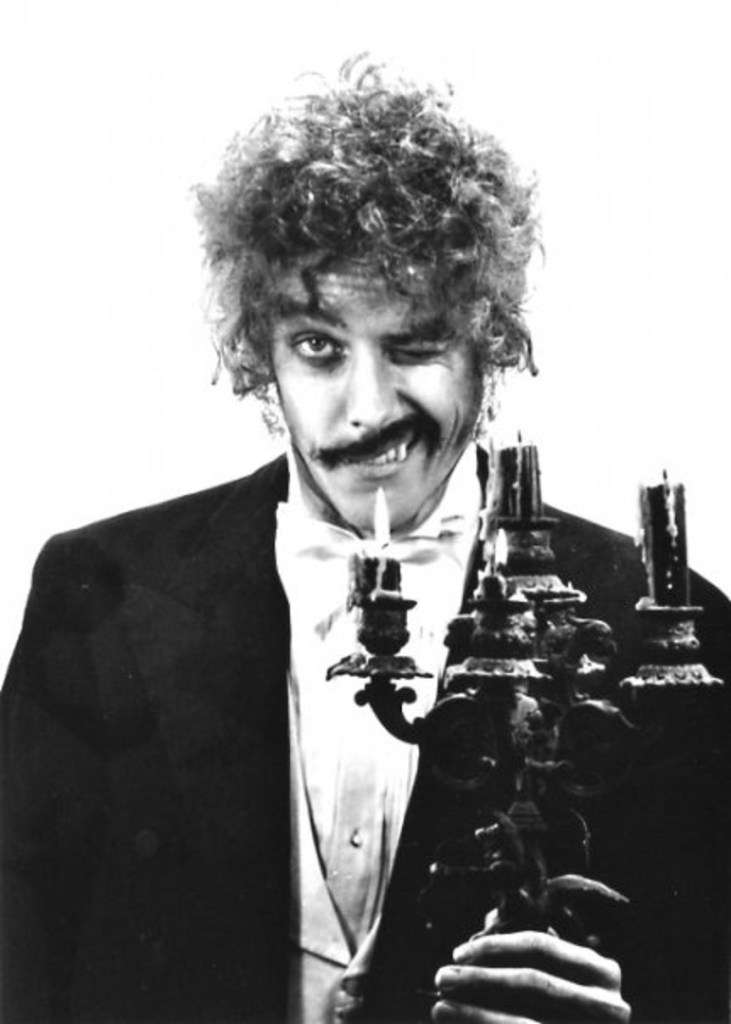

HORROR HOSTS

In 1969, Larry Vincent began his career as “Seymour” on KHJ-TV‘s Fright Night. As horror host, Seymour heckled and provided sarcastic commentary with the low-budget horror films he screened — occasionally popping into the frame to interact with them in the style later popularized on Mystery Science Theater 3000. He ended his initial run in 1973, at which time hosted Seymour’s Monster Rally on KTLA. His replacement was Moona Lisa, portrayed by Lisa Clark. Her run proved short-lived, however, and Seymour returned in 1974 to host the show, now rebranded Fright Night with Seymour (1974). Vincent died of cancer, though, in 1975. This time he was replaced by Grimsley (Robert Forster), who hosted Fright Night until it ended its run in 1978.

While Seymour, Moona Lisa, and Grimsley were screening old monster movies, modern horror from the ear was filled with fashionable occult and satanic themes. Many of the best examples came from Hollywood as well as the studio systems of the UK and Italy. In music, meanwhile, satanic imagery came to be most closely associated within the burgeoning Heavy Metal scene — although that was then a musical phenomenon initially more associated with the UK than California.

Led Zeppelin‘s Jimmy Page was surely the most famous follower of Aleister Crowley — also known as The Great Beast 666, Perabduro, Ankh-f-n-khonsu, and “the wickedest man in the world.” The guitarist was commissioned to score Kenneth Anger’s underground film, Lucifer Rising, after the original score, written and performed on a Moog by Mick Jagger, was instead used for Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother. By the time Lucifer Rising was finally completed, however, Anger used a score written by Charles Manson associate and convicted murderer, Bobby Beausoleil.

GLAM, GOTHABILLY, DEATH ROCK, AND HORROR PUNK

There was also a camp science-fiction/horror aspect to glam rock, another theatrical 1970s musical phenomenon more associated with London than Los Angeles. In the case of glam rock, however, there were notable Los Angeles exponents like Brett Smiley, Jobriath, Sparks, and Zolar X. Glam rock and celluloid combined most famously in the British film, The Rocky Horror Picture Show. In Los Angeles, however, Phantom of the Paradise is perhaps even more loved.

Phantom of the Paradise tells the story of a disfigured composer, the Phantom, whose music is stolen by a producer at Death Records, Swan, played by Paul Williams. Williams, who also wrote the music, wasn’t exactly a glam rocker (he’s perhaps best known for having written several hits for the Carpenters) but he and director Brian De Palma tapped into the aesthetics of glam and classic horror for the film. Fictional rocker Beef comes across like a cross between Jobriath and Frankenstein’s monster. The Undeads are clearly inspired by the expressionist aesthetics of Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari.

The film, appropriately, opened on Halloween of 1974. It was a box office flop in the US but hugely popular in Mexico City, Winnipeg, and Central America. Perhaps it’s in part because Los Angeles is home to so many Canadians, Guatemalans, Mexicans, and Salvadorans that it has such a huge cult following in Los Angeles to this day.

While Phantom of the Paradise drew upon classic Universal horror, 1950s B-movie horror was an obvious and arguably more appropriate influence on DIY garage punk bands that emerged in the mid-1970s. The Cramps were born in 1976 with songs like “I Was a Teenage Werewolf” and “Zombie Dance.” They called their music, initially a manic take on rockabilly, “psychobilly.” Although largely associated with New York’s punk scene, they were from Sacramento and for most of their existence, Lux Interior and Poison Ivy lived in an East Hollywood. Additionally, although their debut was recorded in Memphis, every studio album that followed was recorded either at various Hollywood studios or Earle’s Psychedelic Shack in Thousand Oaks.

While the Cramps created psychobilly, a similar subgenre called horror punk crawled forth from New Jersey, thanks to its progenitors, the Misfits. The Misfits were similarly steeped in 1950s monster movies and B-movie sci-fi. The band’s logo was based on the logo of Famous Monsters of Filmland. Singer Glen Danzig disbanded the group in 1983 and formed Samhain, a Deathrock band named after the Celtic holiday from which Halloween is derived. They released their debut on Danzig’s Plan 9 label.

From 1989 – 2005, Danzig lived in a suitably creepy Craftsman home in Los Feliz before moving to a home in Cheviot Hills that overlooks a golf course and was once owned by Lucile Ball. Since 1987, however, he’s continued to make dark metal with his band, Danzig. Meanwhile, Danzig’s former creepy Craftsman thankfully looks pretty much the same as it did when he lived there — overgrown and run-down with a bare light dangling over the porch. I can’t remember if there’s still a pile of bricks in the yard.

Writing in 1978, music journalist Nick Kent echoed Stickeny’s description of the Doors, referring to them and Velvet Underground as “Gothic rock.” German singer Nico, after leaving the Velvet Underground, recorded the Marble Index, which is surely one of the most Gothic albums committed to record. Still, it’s doubtful that any fan of the Doors and the Velvet Underground was ever identified as a Goth until the 1980s when fans of bands like Bauhaus, the Cure, and Siouxsie & the Banshees began to be referred to thus.

The Goth subculture emerged from post-punk and “positive punk” clubs like London’s Batcave and Leeds‘s F Club and Le Phonographique, from which would emerge bands like Alien Sex Fiend, Sex Gang Children, Sisters of Mercy, and Southern Death Cult (the singer of which, Ian Astbury, would later move to Los Feliz and sing with the Doors).

☠️ ❦ ☠️

GOTHIC ROCK

Around the same time that Goth was forming in the UK, Los Angeles was spawning a similarly styled music and subculture that quickly came to be known as Deathrock. Deathrock shared many of Goth’s antecedents — namely psychobilly, horror punk, and horror films. As a descriptor, “death rock” goes all the way back to those fatalistic teenage songs of the early rock ‘n’ roll era, songs like “Leader of the Pack,” “Ebony Eyes,” “Patches,” “Teen Angel,” “Teen-age Heaven,” and “Tell Laurie I Love Her.” In the 1970s, there was a new wave of teenage death pop with songs like “Ode to Billie Joe,” “Dead on Arrival,” “Honey,” and “Timothy.”

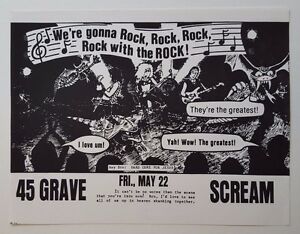

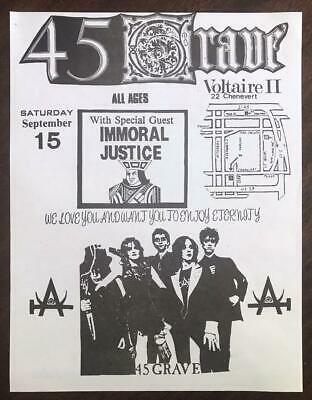

The first Deathrock band of significance was 45 Grave, whose debut recording was a cover of Don Hinson and the Rigamorticians‘ monster-novelty song, “Riboflavin Flavored, Non-Carbonated, Poly-Unsaturated Blood.” It was included on a compilation, released in 1980, titled Darker Skratcher. Christian Death recorded their demos in 1981. Other local Deathrock bands included Burning Image, Kommunity FK, Ex-VoTo, Eva O, and The Super Heroines. Long Beach punks T.S.O.L took a Deathrock turn around 1981 before changing directions again into a metal band. The primary Deathrock venue was the Anti Club, which opened on Melrose in 1979 but closed at a different location in 2001.

🦉 ❦ 🦉

If the Deathrock era needed a Deathrock horror hostess, it arrived in the form of Elvira, Mistress of the Dark. As portrayed by Cassandra Peterson, Elvira was a sort of punk-Valley Girl hybrid who, visually, referenced Moona Lisa, Vampira, and Morticia Adams before her. Two years after the end of Fright Night, the concept was revived as Movie Macabre which ran from 1981-1986. In 1988, she starred in a film, Elvira: Mistress of the Dark. Peterson revived the character for 2001’s Elvira’s Haunted Hills, 2010’s Elvira’s Movie Macabre, and 13 Nights of Elvira.

🧟 ❦ 🧟

If there was a fictional cinematic expression of Deathrock, it has to have been John Russo‘s Return of the Living Dead, which was both a throwback to classic zombie films and featured music by bands including 45 Grave, the Cramps, the Flesh Eaters, T.S.O.L., and the Damned, by then deep into their Goth phase. By then, however, “Goth” had become a more common name than “Deathrock,” even in Los Angeles. and there was really nothing to separate them other than eight time zones. Deathrock wasn’t the only subgenre absorbed into Goth, which by the late 1980s made space for Dark Wave, Cold Wave, New Grave, EBM, Ethereal, Dream-Pop, Industrial, Raincoat Rock, and other “dark alternative” genres.

Sam Rosenthal‘s Projekt Records was formed and operated out of Garden Grove from 1983 until at least the mid-1990s, after which it relocated to Portland. In 1992, Angeleno Brian Perera founded Cleopatra Records, one of the two best-known music labels associated primarily with Goth music.

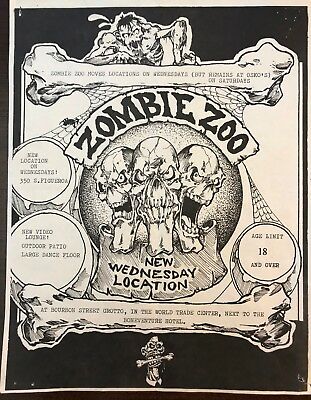

Goth nights and clubs have, for the most part, proven less durable than the subculture they are part of — although two figures — Greg Peck and Joseph Brooks — seemingly have a hand in half of them. Those two met at Humboldt State University in 1975 and in 1978, at the Sex Pistols‘ final show, met Kid Congo Powers, who convinced them to come to Los Angeles. After a stint in London, where they hung out at Steve Strange‘s Club For Heroes, they returned to Los Angeles and opened the Veil in 1981 — a Deathrock, Goth, and New Romantic club — in Hollywood. They also opened the record store, Vinyl Fetish, and hosted KROQ‘s The Import Show where they broke many bands locally that were relatively unknown outside of Los Angeles. They later went on — both together, solo, or in collaboration with others — to found similar Goth-related club nights including Fetish, Helter Skelter, Scream, Sin-A-Matic, and Coven 13. Brooks also started the L.A. Fetish Ball with James Stone from Club Fuck! Peck died in 2018.

Goth subculture has proven unexpectedly deathless compared to other subcultures from that era. By the 1990s, Goth was probably bigger than ever and Goths were always good entertainment on trashy daytime talk shows and even trashier tabloid news segments. Meanwhile Goth continues to grow and spawn new subcultures in Southern California. In addition to Beach Goth, born in North Orange County, there are also Mall Goths. Mall Goth shop, Hot Topic, was launched in the suburban Inland Empire‘s Montclair Plaza in 1988. There are also, not wholly surprisingly, Cholo Goths, who have their own night at The Lash Social.

The longest still-running (well, when there’s not a pandemic) dance club in Los Angeles is Bar Sinister, a goth night established in 1998 at Boardner’s. The same folks, in normal times, also host Wenzday’s Party & Vampire Lounge at the same venue. Other goth nights and venues include Club Disintegration, Club Purgatory, Goth House Party, Grave Beat, Klub Terminal, and Ruin. Naturally, a huge part of Goth subculture is visual, and so there are Goth-leaning boutiques like Ipso Facto (established in 1989 by Bob Medeiros and Terri Kennedy of Stone 588), Shrine of Hollywood (since 1994), Meowmeowz! (run by Veronika Sorrow, former hostess of Goth nights the Wake and Funeral and singer in Untoward Children), and Local Boogeyman. A Halloween-only chain, Halloween Club, opened its first location in 1991.

🦇 ❦ 🦇

CONVENTIONS & EVENTS

In normal years — that is, years in which we’re not attempting to get a handle on a disease pandemic — there are all sorts of horror conventions, film fests, ghost tours, and other events like Boyle Heights Most Haunted, Dark Circus, Monsterpalooza, and ScareLA. There are usually events centered on Gothic holidays like Día de Muertos, Halloween, Obon, and Setsubun. This year, of course, has been different. There are, though, still some outdoor events — horror films and thrillers (mostly family-friendly) screened in parking lots, pumpkin patches, farm mazes, and virtual events. No escape rooms, though, as far as I know.

It still feels like Halloween, to me, though. After eight or so relentless heatwaves that had me plotting my escape to the nearest snow-capped mountain, it’s finally pleasant outside and I can enjoy walks in the misty gloomy mornings. There are sycamore leaves all over the ground just waiting to be pointlessly blown around by illegal, polluting, noisy, dust-churning leaf blowers. Yards are decorated with fake skeletons and gravestones. That awful polyester cob-webbing — the Halloween decoration equivalent of single-use plastic bags — is stretched unconvincingly over shrubs where it will inevitably trap and kill insects and birds before being taken to a landfill.

Meanwhile, a growing number of people prefer not to logic but to what their gut tells them — placing their faith in crystals, amulets, horoscopes, and magical bracelets rather logic, science, and experts. Our outgoing president/reality television star has transformed his once-grand old party into a Jim Jones-style death cult. Huge numbers of people are less concerned with the very real climate catastrophe, health, and housing crises than they are imaginary Satanic child sex-trafficking rings run by politicians out of non-existent basements in pizzerias. If this doesn’t scare you, you’re already dead. Rosabelle believe!

🕸️ ❦ 🕸️

As always, additions are considered and corrections are appreciated. Have a safe, responsible, and fun Halloween and a happy Día de Muertos!

🥀 ❦ 🥀

FURTHER READING

“A Journey Through the Gothic Landscape of Orange County” by DKelsen

“City of (Dark) Angels: How L.A. Helped Birth Goth and Is Keeping the Culture Alive” by Lina Lecaro and Lisa Derrick, 2019

Southern California Haunt List

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hey Freelancer!, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, the Los Angeles County Store, Sidewalking: Coming to Terms With Los Angeles, Skid Row Housing Trust, the 1650 Gallery, and Abundant Housing LA.

Brightwell has been featured as subject and/or guest in The Los Angeles Times, VICE, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, Office Hours Live, L.A. Untangled, Spectrum News, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, Notebook on Cities and Culture, the Silver Lake History Collective, KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, All Valley Everything, Hear in LA, at Emerson College, and at the University of Southern California.

Brightwell is currently writing a book about Los Angeles.

You can follow him on Ameba, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, iNaturalist, Instagram, Letterboxd, Mastodon, Medium, Mubi, the StoryGraph, Threads, TikTok, and Twitter.