1915

Birth of a Nation was released. It was the most profitable American film of all time until Disney’s Snow White & the Seven Dwarves (1937). In this critical darling, director D.W. Griffith dramatically depicts a mid-19th century south plagued by mulattos and abolitionists who scheme to keep the white man down and raise up the black man in what is, to its intended audience, an obviously grotesque perversion of natural order. In government sessions, the reconstruction-empowered black politicians (played buffoonishly by white actors) take off their shoes and feast on fried chicken. Luckily, the chivalric Ku Klux Klan rides to the rescue.

This version of history was angrily disputed (famously by W.E.B. Du Bois, among others) but remained pretty much the accepted version of history until well after World War II. The NAACP, founded just five years earlier, organized nationwide protests. There were riots in Philadelphia and Boston. Cities in Illinois, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio and Pennsylvania refused to show the film. In Indiana, a white man murdered a black stranger and blamed it on having seen Birth of a Nation. However, the film received a special screening at the White House, where president Woodrow Wilson supposedly remarked, “It [the film] is like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.” The quote was later argued to be from someone else but the film was still marketed as “Federally-endorsed.”

It is still widely praised and has been for decades for its pioneering technical achievements, which, arguably, are exaggerated to excuse its bafflingly continuing popularity. Nearly all of these achievements have since been discovered in earlier films and yet even mainstream critic Roger Ebert considers it a great film, stating, “The Birth of a Nation is not a bad film because it argues for evil. Like Riefenstahl’s Triumph Of the Will, it is a great film that argues for evil. To understand how it does so is to learn a great deal about film, and even something about evil.” This from a guy who doesn’t like Blue Velvet or A Clockwork Orange, because of the subject matter. I guess racism is OK when it’s old. You know, they just didn’t know any better back then.

On the other hand, critic Jonathan Lapper wrote that, “[M]ost critics [have] developed a pattern of response to the film that continues to this day: Praise the film’s techniques, deplore the film’s content, let technique trump content, declare the film a masterpiece.” He argues that it is disingenuous to separate the film’s content from its technique.

I personally find the importance of context and position in a cinematic time line to be sometimes interesting but irrelevant to quality. The example I will use to make my point is this: If they discovered some old wax cylinders with the music of Candlebox would that mean that Candlebox were now good simply because they were now undeniably pioneers? The songs would sound the same; therefore, how can the qualitative assessment of art change based on extrinsic factors? If they discovered a silent film with the same purported technical achievements but made two years earlier, is Birth Of a Nation no longer a masterpiece, even though the film itself hasn’t changed? Of course not. The film is crap and remains crap because the subject matter is repulsive, the storytelling idiotic compared to the techniques Griffith borrowed from bad fiction and the acting and everything else is awful. I defy anyone to try to watch it.

Lincoln Motion Picture Company

The same year Birth of a Nation was released, the The Lincoln Motion Picture Company was founded in Nebraska. Organized by brothers George and Noble Johnson with the aim of encouraging black pride whilst upholding the social order of the day, it was the first company to produce what came to be known as “Race Movies,” which tried to balance an accurate depiction of black folks’ lives and at the same time actively promote a positive image, usually (in the case of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company) through the production of family films. In 1918, John Noble directed Birth of a Race which attempted to suggest that all races are equal. It was panned by critics but popular with black audiences who increasingly turned to Race Movies instead of Hollywood’s product, which invariably limited depictions of blacks to comedic coons, sambos, mammies, toms, &c.

Oscar Micheaux (1893-1951)

Illinois-born and Kansas raised Oscar Micheaux, a child of former slaves, moved to South Dakota where he farmed. He formed a motion picture company in 1919 and that same year directed (and wrote and produced) The Homesteader, about a black homesteader in South Dakota.

Micheaux’s second film, Within Our Gates, from 1920, is the oldest surviving film made by a black filmmaker. It ran into significant problems with censors on account of its depictions of rape and lynchings at the hands of white people, which were probably viewed as not at all analogous to blacks raping whites in Birth of a Nation a few years earlier. In 1924, he made Body & Soul, which was the first cinematic appearance of Paul Robeson. 1931’s The Exile was the first black talkie. Micheaux went on to direct 40 films, making him one of the most prolific independent filmmakers of any era.

In 1926, Carter G. Woodson, also a son of former slaves, established Negro History Week in February on the week in which both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass’ birthdays are observed. He expressed the desire that someday it wouldn’t be necessary to have a special period of observance because hopefully black history would become integrated with history as a whole in the future.

Eddie Cantor Fred Astaire

In the 1930s, the depression and the advent of talkies made film-making a more cost-prohibitive operation. Blackface remained popular in Hollywood with Jimmi Durante (The Phantom), F. Gosden and C. Correll (Amos ‘n’ Andy In Check and Double Check), Mickey Rooney (Babes In Arms), Fred Astaire (Swingtime), Al Jolson (Wonder Bar) and Eddie Cantor (Roman Sandals) all donning the makeup and cartoonish mannerisms for their films.

Black actors continued to find roles in race movies which, by then were usually white-written films made for white-owned production companies but still with black audiences in mind. Although less overtly racist than Hollywood, these films usually called for blacks to conform to well-meaning, non-threatening stereotypes with spiritual-singing, tap dancing and comedy usually being showcased by up-and-coming actors like Lincoln “Stepin Fetchit” Perry, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Louise Beavers, Hattie MacDaniel, Dewey “Pigmeat” Markham, Jackie “Moms” Mabley and Herbert Jeffrey, a popular singing cowboy. Occasionally Hollywood made films along the same lines as the actors grew more famous. Films from the 1930s and ’40s included The Blood of Jesus, Go Down Death, Son of Ingagi, Juke Joint, Marching On!, The Girl in Room 20, On One Blood, Cabin In the Sky, Harlem Is Heaven, Stormy Weather, Jivin’ in Be-Bop, Hi-De-Ho, Ebony Parade, Two Gun Man From Harlem, The Bronze Buckaroo, Harlem On the Prairie, Look-Out Sister, Harlem Rides the Race, Hallelujah!, Green Pastures and Song Of the South.

With the dawn of television in the late 1940s, Hollywood took various measures to distinguish its product from its new competition. Just having black leads set it apart from the new medium since only one show of the 1950s starred a black actor, the short-lived Beulah which, not surprisingly, was about a maid in the mammy mold. It wasn’t until the mid 60s when a black actor, Bill Cosby, starred in a TV show that didn’t stereotype — I, Spy. The 1950s and ’60s would see an unprecedented boom of films dealing with bigotry and other racial issues. No longer were they mainly targeted at black audiences but for an increasingly integrated mainstream and often, seemingly, for white audiences. They included Cry the Beloved Country, Lilies of the Field, Go Man Go, The Bedford Incident, Goody My Lady, A Patch of Blue, Edge of the City, Duel At Diablo, Edge Of the City, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat of the Night, To Sir With Love, For the Love of Ivy, The Lost Man, Something Of Value, The Defiant Ones, Carmen Jones, Porgy & Bess, Paris Blues, A Raisin In the Sun, Pressure Point, I Passed For White and Pinky.

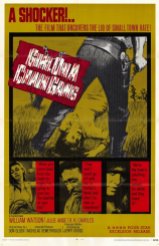

At the same time as Hollywood tried to present (invariably white visions) of racial issues with sanitized portrayals and safe stories about liberal whites getting along with forgiving blacks, independent film-makers often exploited race issues to stir up audiences with shocking depictions of racism, rape and race-mixing in grindhouses with films like Free Black & 21, Black Rebels, Checkerboard, My Baby Is Black, Murder In Mississippi, Girl On a Chain Gang, and The Black Klansman.

In the late 1960s, Julia (1968-1971) and The Bill Cosby Show (1969-1971) featured black actors in starring roles miles away from their predecessors.

Med Hondo Ousmane Sembene Djibril Mambety

La Noire de… Touki Bouki

Meanwhile, in Africa, Senegalese author-cum-director Ousmane Sembene made the first African feature by a black director, 1964’s La Noire de… In 1969, an African film festival, FESPACO, was established in Burkina Faso. In the next few years, many Africans started making their own films about themselves like Med Hondo‘s 1969 O Soleil O, and fellow Senegalese Djibril DiopMambety‘s Touki Bouki. These provided a welcome departure from the Eurocentric tales of colonial adventure like Tarzan, Zulu, and The African Queen, which portrayed a wild, dangerous and dark continent as imagined (and often filmed in) Hollywood studios.

In 1969 Gordon Parks made The Learning Tree. The following year, Melvin van Peebles made the daring Watermelon Man and Ossie Davis made Cotton Comes to Harlem. Once again black film-makers were making films specifically for black audiences. These films ushered in the era of “blaxploitation.” I haven’t seen the etymology of the term but I always assumed that the “exploitation” was of the black audience which had been ignored as a distinct group since the 1940s. In 1971, van Peebles made Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song which grossed $14 million and Gordon Parks made Shaft for Columbia. As with earlier black cinema, many of the films were made by white film-makers and because of the increasing focus on crime, inner city poverty, pimps and drugs, many felt the films depicted blacks negatively and as stereotypically as ever. Certainly non-black audiences took a voyeuristic view of these fictional tales and today “blaxploitation” is often used almost apologetically, as if the films exploited black actors (rather than a largely-ignored audience) for white audiences who viewed the films with ironic bemusement. The NAACP saw it the same way, apparently, and responded by forming the Coalition Against Blaxploitation to voice its concerns with the genre. By 1975 it had run its course anyway and it would be some time before American films dealt so often with stories centered around black stars.

In 1976 Negro History Week was bumped up to include the entire month of February and re-named Black History Month following the efforts of the ASALH– the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History.

On television, a crop of shows sprang up, filling the Hollywood void with not just one or two black stars or extras, but often predominately black casts like Good Times, That’s My Mama, Sanford & Son, What’s Happening, The Jeffersons, Room 222, and Fat Albert & The Cosby Kids.

In the 1980s, black actors often crossed over to mainstream superstardom. Eddie Murphy, Denzel Washington, Danny Glover, Richard Pryor and Whoopi Goldberg all starred in films in which race was scarcely an issue, if not for a few jokes. On TV there were shows like The Cosby Show, 227, A Different World and Amen. Film and TV usually presented a version of reality in which racism was a thing of the past and everyone got along, teasing aside.

It wasn’t until the late 1980s and early ’90s that a significant group of black film-makers emerged once again into the national conscience. These directors all took a starkly different view and depicted an America with crumbling inner-cities, gang violence, drug epidemics and open racism. Spike Lee(School Daze, She’s Gotta Have It, Do the Right Thing), Reginald Hudlin (House Party), John Singleton (Boyz N the Hood), Mario van Peebles (New Jack City), The Hughes Brothers (Menace II Society), Ernest Roscoe Dickenson (Juice) are prime examples. Even a comedy like House Party has the late, great Robin Harris getting harassed by police. Again, a significant portion of the audience were watching with an outsider’s voyeurism and concern. The late 1980s and early ’90s were, in fact, pretty rough, as anyone alive then probably remembers.

In the late 90s up to the present, low-budget direct to DVD films targeted at black audiences have absolutely exploded as film-making has again become cheap and easy with new technology. The range, robustness and diversity suggest that the cyclic nature of black cinema is pretty much a thing of the past, as every week sees another handful of films which most people probably have never heard of and yet sell enough to encourage more in the weeks to come. The following are just a few, but a troll through Amoeba Hollywood’s Black Cinema selections will probably leave you feeling a little overwhelmed by currently prolific genre.

*****

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, writer, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities — or salaried work. He is not interested in writing advertorials, clickbait, listicles, or other 21st century variations of spam. Brightwell’s written work has appeared in Amoeblog, diaCRITICS, and KCET Departures. His work has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft & Folk Art Museum, Form Follows Function, Los Angeles County Store, Skid Row Housing Trust, and 1650 Gallery. Brightwell has been featured in the Los Angeles Times, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, and on Notebook on Cities and Culture. He has been a guest speaker on KCRW‘s Which Way, LA? and at Emerson College. Art prints of his maps are available from 1650 Gallery and on other products from Cal31. He is currently writing a book about Los Angeles and you can follow him on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Click here to offer financial support and thank you!