Happy Lunar New Year — the year of the Fire Horse!

The Lunar New Year widely celebrated in Korea, Mongolia, Ryukyu, Taiwan, Tibet, and Vietnam… and historically, Japan. Although China is a diverse country and with people such as the Dai, Miao, Kazakhs, and Uyghurs (who mark other dates as the beginning of the new year), Lunar New Year is also, of course, celebrated across China and by most of China’s roughly 50 million diasporic Chinese. For this reason — and others — Lunar New Year is often referred to as Chinese New Year.

POWER SOFT AND HARD

Chinese New Year is one of the tools in the arsenal China’s soft power — like Chinese restaurants, Hanzi smatter tattooes, dancing humanoid robots, and Labubus. China’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism and other agencies use Lunar New Year to promote a benevolent image of a China focused on harmony and renewal — which is quite a contrast with the US — a nation that wields soft power (e.g. pop music, Hollywood films, social media platforms, etc) but backs it up with the coercive threat of hard power, too. That’s not to suggest that China is governed by committed pacifists. In the last 50 years, the PRC has engaged in military skirmishes with India, the Philippines, and Vietnam — and nearly continuously harassed Taiwan which, although never governed by the People’s Republic of China, is somehow supposedly integral to its existence… but nothing that approaches the imperialist interventions of the US during the same period, which have seen military actions in Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Côte d’Ivoire, Cuba, Cyprus, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Gabon, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea-Bissau,Haiti, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kenya, Kuwait, Laos, Lebanon, Liberia, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Oman, Palestine, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, the Philippines, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, United Arab Emirates, Vietnam, Yemen, and Yugoslavia… to name a few.

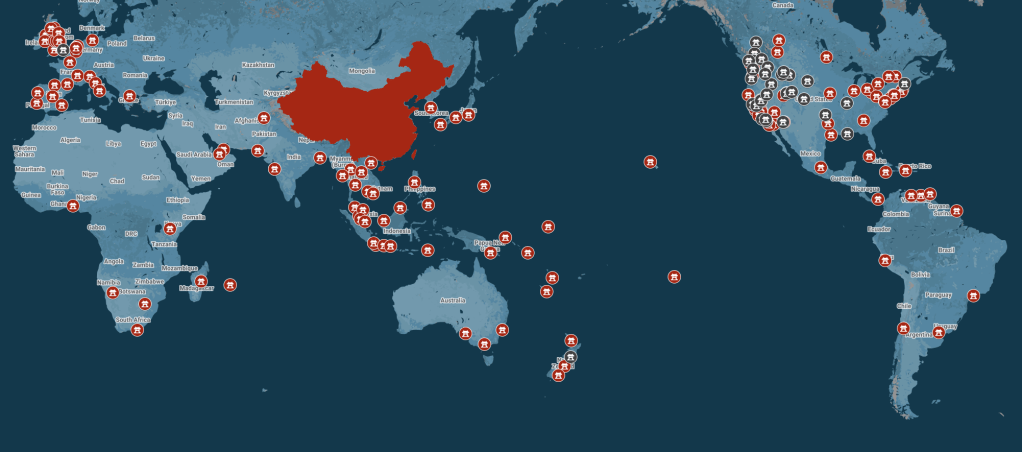

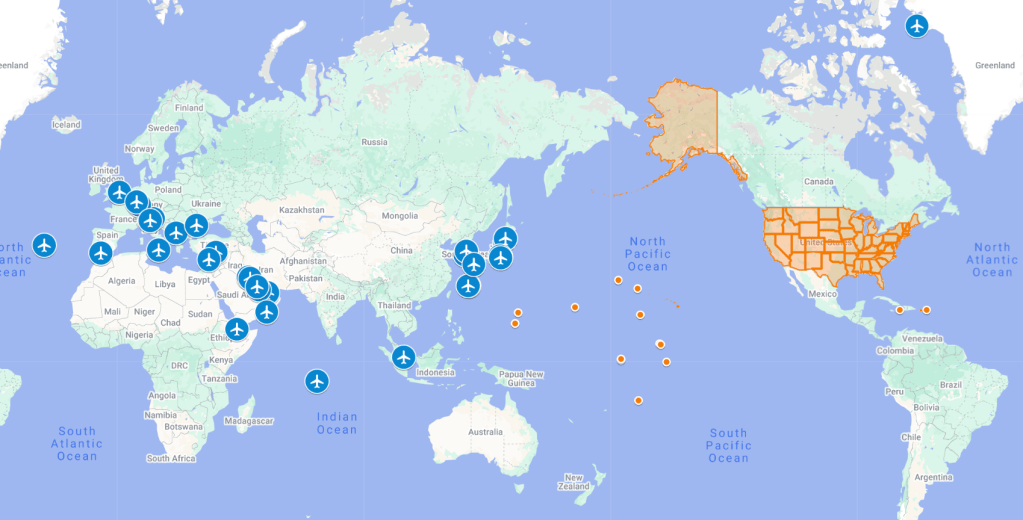

As someone who categorically opposes repression, imperialism, torture, environmental devastation, forced labor, and forced re-education — and who values democracy and civil liberties — you will not often find me championing the regimes of either China nor the US — nor the governments of many other countries, for that matter. I do, though, prefer soft power to hard power. The disparity in global presence is what led me to reflect on the literature of empire and influence — topics which were on my mind after reading Daniel Immerwahr‘s How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States and Jung Chang‘s Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister: Three Women at the Heart of Twentieth-Century China. So I made a map of both Greater America and China and Chinatowns. Americans don’t really do American enclaves. You won’t find “Americatowns” when traveling. What you will find, however, are American military bases which, for better or for worse, are our country’s closest equivalent. You won’t find all of them, though, because whilst Chinatowns are promoted, the locations and existence of many American military bases are classified.

China, on the other hand, has just one full-fledged “official” military base outside of China, at the Port of Doraleh in Djibouti. True, there is a joint logistics and training center in Cambodia, a paramilitary outpost in Tajikistan, a listening station in Cuba, a deep space-tracking station in Argentina, and a state-owned shipping facility in Peru — but nothing that comes close to America’s global military footprint. And while I certainly would never say that China doesn’t nurse any imperial ambitions — it throws around its military might a lot less than the US.

Where there are believed to be over 750 US military bases, there are roughly 150 Chinatowns. I’ve visited a few, like the ones in Vancouver, Philadelphia, and elsewhere. When I visited Mexico City in 2017, I was disappointed in Barrio Chino, which offered little in the way of Chinese anything beyond the aesthetics of paper lanterns and paifang gates. It seems Mexico’s Chinese population is much more fully represented in Mexicali’s barrio La Chinesca. Last year, when I went to London‘s Chinatown in Soho, I was surprised to learn that its roots in the neighborhood only stretched back to the 1950s… and that was only officially recognized by the Westminster City Council on 29 October 1985.

CHINATOWNS — THE TIGER OF ETHNIC ENCLAVES

Chinatowns are one of the most common and widespread types of ethnic enclaves in the world, They’re found on every continent inhabited by humans. All of the Little Italies, Little Indias, Koreatowns, and Japantowns, combined only add up to roughly the same number of Chinatowns as there are in the world. Chinatowns arose not as part of a top-down government effort, though. In the West, including California, Chinatowns were born out of mass migration of poor Chinese fleeing famine, natural disasters, the Opium Wars, and seeking better lives in towns, gold fields, or on massive infrastructure projects beyond China’s borders. Most of the earliest inhabitants of Chinatowns came from Fujian or Guangdong (historically known in the West as “Canton”). Racist laws and systemic segregation precluded them, in some countries, from acquiring or owning property, forcing them to live in small, dense, undesirable sections of cities — which organically became Chinatowns.

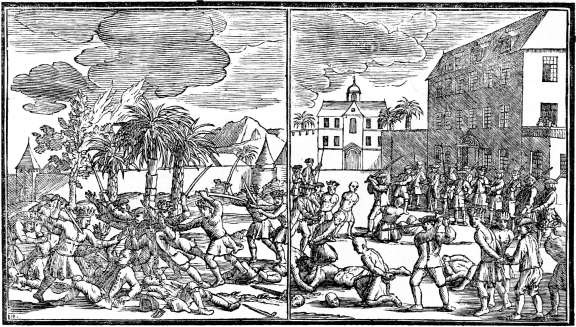

Most Chinatowns arose in the 1800s — but the world’s oldest, Manila’s Binondo, was established in 1594 by Spanish colonists.. It was a colonial creation designed to keep the Chinese population separate from Filipinos and controllable. Chinatowns in Southeast Asia tended to follow a different trajectory than those in the West. The Chinatowns that arose in cities like Bangkok and Saigon were built on a foundation of maritime trade and economic dominance. In Asian countries, Chinese immigrants often formed what sociologists call a “middleman minority” — dominating the import-export trade, retail, and rice milling. European colonial powers used the Chinese as a buffer class, employing them to collect taxes and manage local trade on behalf of the colonizers, which granted them economic power but also made them targets of local resentment in British Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, French Indochina, and the Spanish-Las Islas Filipinas.

Anti-Chinese pogroms erupted several times over the centuries. The Sangley Rebellion (1603) in the Philippines led to the killing of over 20,000 Chinese. An estimated 10,000 Chinese were murdered in the Batavia Massacre (1740). They continued into the 20th century with anti-Chinese race riots in Pyongyang (1931), Yangon (1967), Kuala Lumpur (1969), Jakarta (1998). The anti-Chinese violence and state-sponsored repression are primary reasons why a significant percentage of immigrants from Southeast Asian countries (especially Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Vietnam) in Los Angeles are ethnically Chinese. In Los Angeles, the intersection of Chinese and Southeast Asian culture is most evident in restaurants. In the San Gabriel Valley, restaurants serving Hainan Chicken are often owned by Singaporean or Malaysian Chinese and Pho restaurants are often owned by Chinese Vietnamese (Hoa). Indeed, those dishes — as well as iconic items like Gyoza, Lumpia, Nasi Goreng, Pad Thai, and Ramen — wouldn’t exist were it not for Chinatown. American Chinatowns, meanwhile, gave the world Crab Rangoon, Beef and Broccoli and Chop Suey.

Speaking of Overseas Chinese Cuisine, its interesting how comparatively limited the expressions of Chinese soft power are compared to other cultures. Documentaries, like The Search for General Tso (2014), explain how Chinese cuisine conquered the US, basically following a franchise model born in New York’s Chinatown. Although there had been Chinese restaurants in the US since Canton House opened 1849, they were relatively rare outside of major American cities (cities with Chinatowns) until they started targeting smaller cities and towns where there was no competition. I moved to Columbiam Missouri in 1978 — the same year Amy Chow did, the Taiwanese immigrant who opened House of Chow with her then-husband, Yung Chow, in 1981. The only other Chinese restaurant in town back then was David Chou‘s Chinese Delicacies, opened the previous year. By the end of the decade, Chinese food was an “ethnic” as American as Italian and Mexican whereas sushi, in most of the country, was the fodder of hack stand-up routines and now familiar staples like Korean, Middle Eastern, Indian, Thai, and Vietnamese food were still almost utterly unknown in Middle America.

But whereas many of China’s Asian neighbors have had broader range of soft power — China’s (Labubus aside) has remained primarily culinary. Martial arts films became hugely popular in the 1970s — but those were mostly from Hong Kong and Taiwan. Bruce Lee, of course, was born in San Francisco. There were critically acclaimed Chinese filmmakers in the 1980s like Chen Kaige and Zhang Yimou — but their were strictly arthouse. Similarly, Chinese music has never managed to find a non-Chinese audience — unlike so-called J-Pop and K-pop. There were ethnically Chinese superstars in Asia — but they were inevitably from Hong Kong, Macau, Malaysia, Singapore, or Taiwan — because music that didn’t glorify the revolution was banned. Things have softened nowadays, but Chinese Boy Bands aren’t exactly threatening the global dominance of K-Pop. Nor is Chinese animation rivaling Japanese, nor Chinese dramas rivaling, well, any country’s.

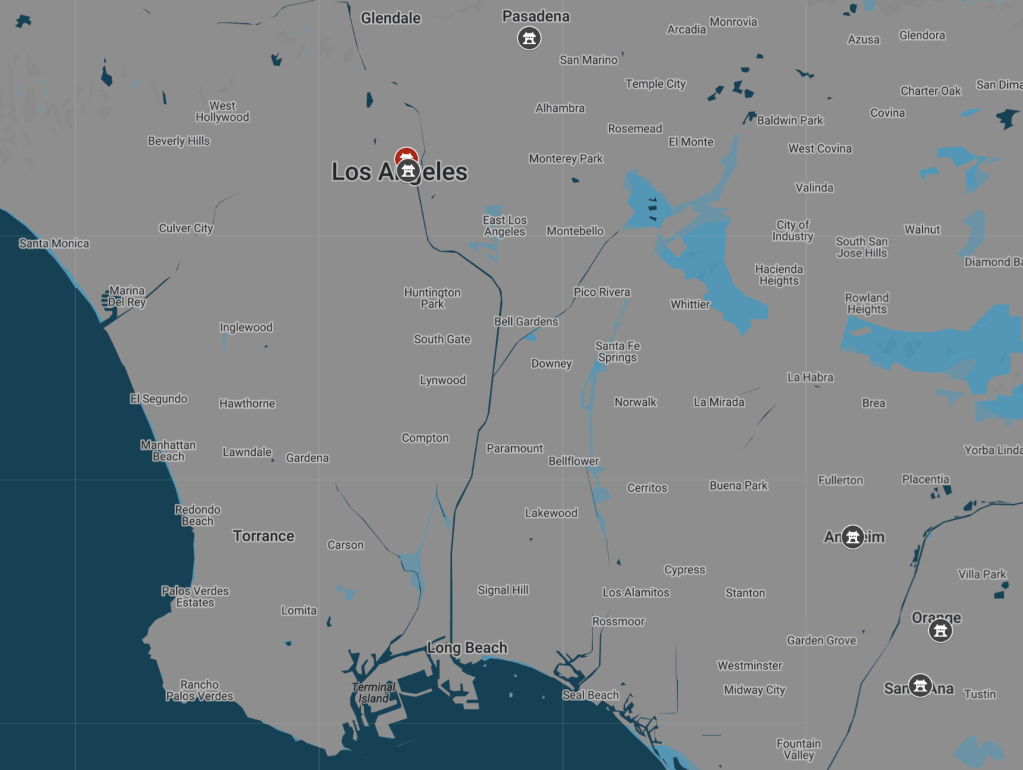

Metro Los Angeles has and has had several Chinatowns. We can surmise that it arose in the 1860s because in 1860, there were only eleven Chinese in Los Angeles… but by 1871, nineteen were massacred in California’s worst mass-lynching. Old Chinatown survived the massacre, only to be demolished decades later to make way for the construction of Union Station. What was left was obliterated by the 101 Freeway. There were small Orange County Chinatowns in Anaheim, Orange, and Santa Ana were dismantled in the early 20th century through a combination of sanctioned arson, forced evictions, and redevelopment. In Pasadena, forced removal, police harassment, and redevelopment erased that city’s Chinatown in the late 1930s — something that city’s historical society seems uninterested in acknowledging.

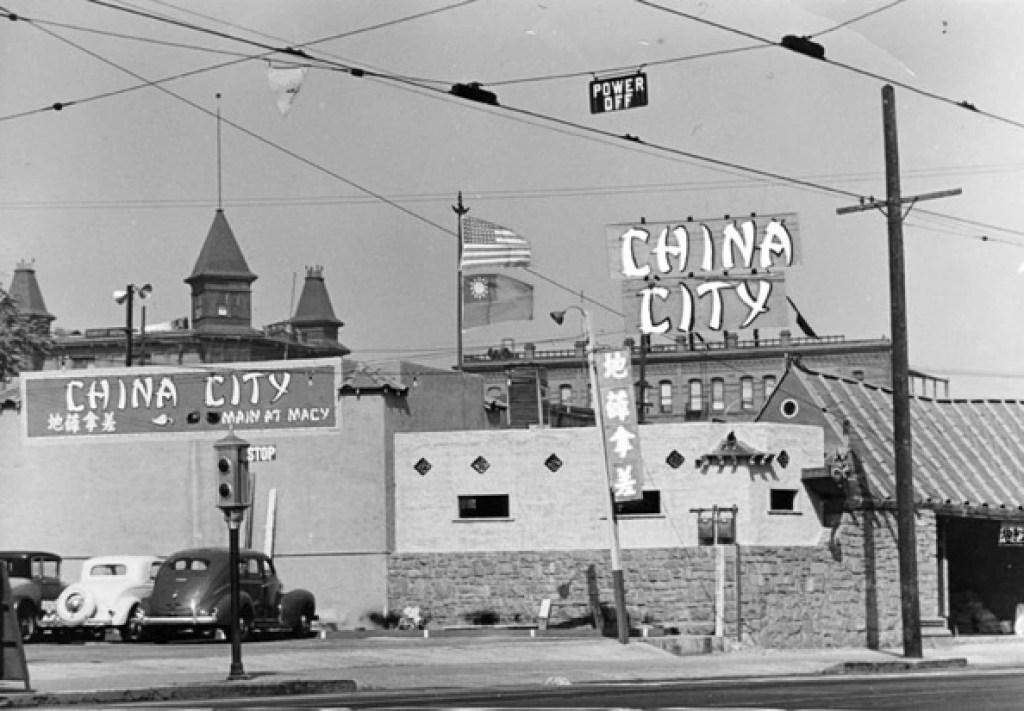

Los Angeles’s current Chinatown essentially began when Christine Sterling‘s China City and a group of Chinese investors’ New Chinatown attractions opened, in what had until then been Little Italy, in 1938. It’s often compared unfavorably to San Francisco‘s — but that one was founded in 1848 when San Francisco was the West Coast‘s main port of entry and is, along with Flushing‘s Chinatown, one of the largest ones in the US – but Metro Los Angeles is home to “suburban Chinatowns” like Alhambra, Arcadia, East San Gabriel, Hacienda Heights, Monterey Park, North El Monte, Rosemead, Rowland Heights, San Gabriel, San Marino, South San Gabriel, Temple City, and Walnut — which, being Chinese “ethnoburbs,” don’t have traditional Chinese enclaves within them.

Of course, since this started as an essay about Lunar New Year, it would be remiss of me not to mention, too, that Metro Los Angeles is home to the largest populations outside of their home countries of Koreans, Taiwanese, and Vietnamese — as well as the nation’s largest communities of Mongolians, Indonesians, and (until recently) Burmese — all communities that include within them many ethnic Chinese. It is also home, both presently and historically, multiple neighborhoods known as Koreatown, Little Taipei, and Little Saigon.

Because there are so many Chinatowns, in fact, many Chinese American organizations and Chinese-dominated suburbs celebrate Lunar New Year on different days — which is, for me (a holiday-loving non-Chinese ) a minor annoyance. I, for one, really don’t like observing holidays except on the actual day. It seems perverse! Imagine if Halloween fell on Tuesday so people decided to trick or treat on the first weekend of November. No one observes Mardi Gras (also today!) on the closest Friday or Saturday. That’s not how holidays work. I wish that all of our Chinatowns, Chinese organizations, and businesses would just join together to make the actual Lunar New Year the day on which we celebrated Lunar New Year. 新年快樂, 恭喜發財, and 萬事如意 — but also Chúc mừng năm mới, あかりーぬ どうゆるー!, 새해 복 많이 받으세요, Happy Lunar New Year… and, lest we forget, Laissez les bons temps rouler!

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always open to paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hey Freelancer!, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, the Los Angeles County Store, Sidewalking: Coming to Terms With Los Angeles, Skid Row Housing Trust, the 1650 Gallery, and Abundant Housing LA.

Brightwell has been featured as subject and/or guest in The Los Angeles Times, VICE, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, LA Times 404, Marketplace, Office Hours Live, L.A. Untangled, Spectrum News, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, Notebook on Cities and Culture, the Silver Lake History Collective, KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, All Valley Everything, Hear in LA, KPCC‘s How to LA, at Emerson College, and at the University of Southern California. He is the co-host of the podcast, Nobody Drives in LA.

Brightwell has written a haiku-inspired guidebook, Los Angeles Neighborhoods — From Academy Hill to Zamperini Field and All Points Between; and a self-guided walking tour of Silver Lake covering architecture, history, and culture, titled Silver Lake Walks. If you’re an interested literary agent or publisher, please out. You may also follow on Bluesky, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, iNaturalist, Instagram, Letterboxd, Medium, Mubi, Substack, Threads, and TikTok.