In the 2000s, Amoeba Music enlisted an army of writers and data entry people to work on an ambitious website that was meant to be a sort of combination of Allmusic, Apple Music, Discogs, Wikipedia, and more. Despite investing a tremendous amount of time, labor and money, the site, as envisioned, never got off the ground. In 2020 — without so much as a head’s up — the plug was pulled. Not only did all of the work of those who toiled in “the Dungeon” quietly die; the musician biographies we wrote were mothballed, Movies We Like vanished, and the celebrated Amoeblog was killed. Luckily, the Wayback Machine has preserved most of it, allowing me to retrieve my work and post it here, with minimal editing, because I think so some of what we did there was worth more than just a wage.

Jobriath was one of the first mass-marketed, proudly, and openly homosexual (aspiring) rock stars. Rather than bringing about stardom, though, the enormous hype resulted in a backlash before he played a note. Since his early death at the age of 37 — and freed from the detriment of obnoxious promotion — Jobriath has been afforded a great deal more interest in death than he received in his poorly-handled and short career. Indeed, today a new generation of less-eagerly-dismissive listeners have found a great deal to enjoy in his clever cosmic camp.

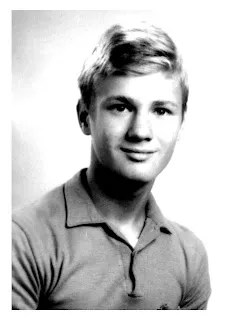

The future Jobriath was born Bruce Wayne Campbell in the appropriately regal-sounding King of Prussia, Pennsylvania on 14 December 1946. His parents divorced when he was young and both remarried. Jobriath and his two full brothers stayed with their father. His father, Jim, was in the military and the family moved frequently. Young Bruce lived on army bases in Maine and Colorado. From a young age, he displayed prodigious musical talent (favoring Sergei Prokofiev) and was drawn to the church, where he played organ. By 1962, his talent was sufficient for a display for Eugene Ormandy, then the conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra. Bruce won the Tri-State Piano Competition by with his performance of an original a piece titled “Diablo.” Around this time, he also started referring to himself as “Job.”

In a sign that he wasn’t like the other guys, he started a trio with his ex-girlfriends Marty and Grace called “Moriah, Tess and Job,” in 1964 — combining references to bothThe Bible and Lerner & Lowe’s Paint Your Wagon. The trio played around Philadelphia and that fall, Job enrolled at Temple University. In addition, he worked at Wanamaker’s, drawn in part to the department store by its enormous pipe organ. After a semester, Job dropped out of school to focus on work and his group, who were offered a residency at the Main Point in nearby Bryn Mawr. His bandmates, though, opted to head off to school after a final performance at Valley Forge Army Hospital.

By 1967 Job was adopting new aliases including Bruce Wayne – dropping his father’s family name — and then Bruce Salisbury — adopting his mother’s — before settling on Jobriath Salisbury. In 1968, the young hippie moved to Los Angeles where he accompanied a piano-playing friend at an audition for Hair at the Earl Carroll Theatre in Central Hollywood When the regular pianist failed to show up, Jobriath sufficiently impressed director, Tom O’Horgan, to secure the part of Woof, a Mick Jagger-obsessed gay who struggles with religion — a part that seemingly could’ve been written for Jobriath.

After its New York City debut, the Los Angeles premiere occurred at the Aquarius Theatre (which the Earl Carroll was renamed in 1968) . Hanging out with his fellow cast members Teda Bracci (future wife of Dusty Springfield) and Zenobia Conkerite, Jobriath first began experimenting with drugs. The west coast production of Hair wrapped up in 1969 and so Jobriath relocated to New York where he appeared for a time in the Broadway cast. Accounts vary as to why he left the production, but he did — and next formed the band, Pidgeon, with Bill Strong Smith (percussion), ex-Hair cast member, Cheri Kohler Gage, and Richard T. Marshall.

In Pidgeon, Jobriath shared lead vocals with Gage (who also played autoharp), played guitar and keyboards, and co-wrote the material with Marshall, credited simply for “poetry.” Producer/session singer Stan Farber got them a contract with Decca Records and arranged for them to rehearse for six months in a house before they entered the studio to record Pidgeon. Containing elements of baroque pop, folk-pop, and quasi-progressive psychedelia; the results, although appealing, failed to find an audience. After the release of the non-album single, “Rubber Bricks/Prison Walls,” the band disbanded. Tiring of life as a hippie and following in his father’s footsteps, in 1970 Jobriath enlisted in the military. After quickly going AWOL, he was sent to Valley Forge Army Hospital and discharged. Upon release, he returned to Los Angeles.

Jobriath next came under the wing of Mike Jeffrey, Jimi Hendrix’s former manager/scam-artist, who managed him as he embarked upon a solo career. Living in an unfurnished apartment, he began working on demos notoriously described by Columbia’s Clive Davis as “mad and unstructured and destructive to melody.” Years later, Jobriath retorted “Clive Davis, who discovered Patti Smith and Barry Manilow said that. So much for sanity and structure.” Intrigued by this hostility, Carly Simon’s former manager, Jerry Brandt, immediately set up a meeting with Jobriath in December 1972.

Brandt flew to Los Angeles. to meet Jobriath, who was by then hustling to pay for his alcohol habit. Describing him as a “beautiful creature,” Brandt invited Jobriath to his Malibu home where, in Brandt’s words, Jobriath showed him “some tricks I didn’t know.” Brandt took Jobriath off Jeffrey’s hands. In early 1973, Jobriath was signed to Elektra for the queenly sum of $500,000. Jobriath Salisbury, claiming spiritual descent, changed his name to Jobriath Boone — although it could also be seen as echoing David Jones renaming himself David Bowie after another frontier hero. Jobriath moved back east and set about creating a backing band several years later, the members of which lived communally and rehearsed in a house in Lambertville, New Jersey. That band, The Creatures of the Street, was made up of Jim Gregory (bass), Steve Love (guitar), Gregg Diamond (drums), and Hayden Wayne (keyboards).

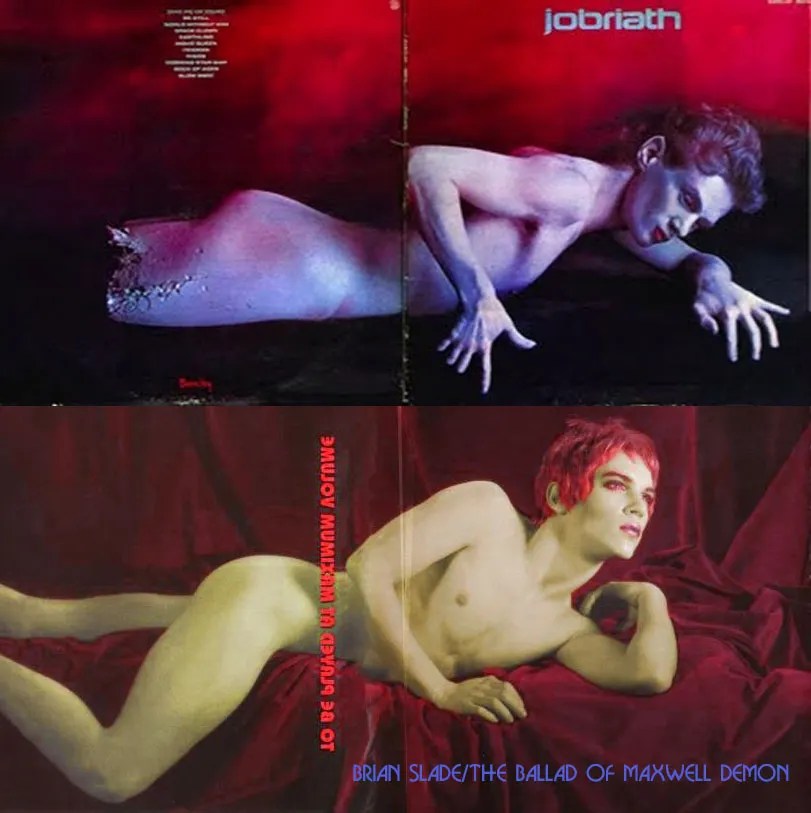

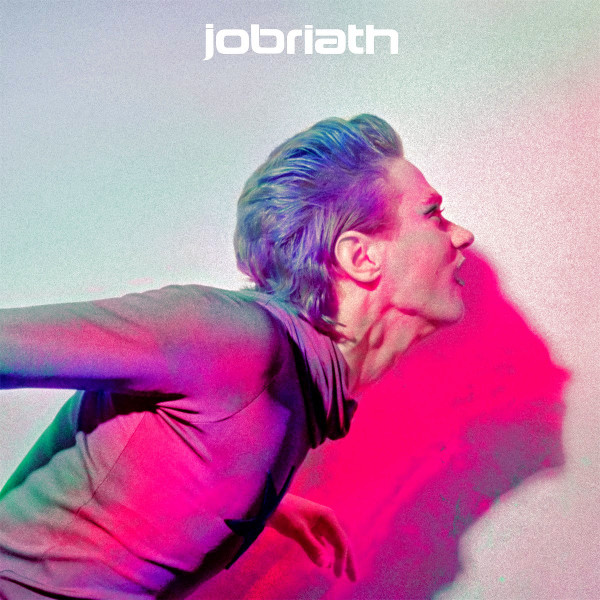

Elektra had enough faith in Jobriath to spend over $80,000 recording his eponymous debut, some of which involved a 55-piece orchestra at London’s Olympic Studios. Roughly half the budget was on promotion with ads in non-music magazines like Vogue, Penthouse, and The New York Times. In New York City, a 41′ x 43′ foot billboard of Jobriath’s face stared down at the crowds in Times Square from the west corner of Broadway and 47th Street. The album cover, Jobriath depicted the artist as a nude, crumbling statue with Vaslav Nijinsky-inspired make-up, and graced 250 buses. It was likewise promoted in London. Brandt handled most of the hype. After suggestions that Jobriath was a cut-rate Bowie clone, Brandt claimed “Jobriath is as different from Bowie as a Lamborghini is from a Model A Ford. On another occasion he described Jobriath as “a leader, as a force, as a manipulator of beauty and art.” In Music Week, he more modestly stated “It’s Sinatra, Elvis, The Beatles, and now, Jobriath.” They’re both cars, it’s just a question of taste, style, elegance and beauty.” “Jobriath is a combination of Dietrich, Marceau, Nureyev, Tchaikovsky, Wagner, Nijinsky, Bernhardt, an astronaut, the best of Jagger, Bowie, Dylan with the glamour of Garbo. He is a singer, dancer, woman, man.”

Despite Brant’s hyperbole, most reviews were highly favorable, including those in Rolling Stone, CashBox, and Record World when Jobriath (1973, Elektra) was released in October. Esquire’s pronouncement of it merely as “hype of the year” was actually one of the few dissenting views. Produced by Eddie Kramer and featuring John Paul Jones and Peter Frampton; Jobriath should’ve sold well for those contributions alone. The music was an ambitious, poppy, and witty mix; populated by spacemen and pierrots; and ranging from the 1930s-ish “Movie Queen” to the sublimely dramatic glam of “Space Clown.” “Blow Away” is probably the greatest ballad of all time that conflates fellatio and the passage of time. Unfortunately, despite of (or perhaps in spite) all it had going for it, the album sold poorly everywhere.

Jobriath had still yet to perform in public. Brandt had miscalculated, thinking that his doing all the talking and the lack of promotion would pique interest in his project.. Brandt promised his live debut would be staged over three nights that December at the Paris‘s Palais Garnier in a production that would cost of $200,000. It was to be followed by a tour of the continent’s major opera houses. Reportedly, the shows would feature Jobriath dressed as King Kong, scaling a model of the Empire State Building, which would rotate to reveal an enormous spurting phallus. Meanwhile, above the phallus, Jobriath was to have transformed into Marlene Dietrich as he approached a suspended grand piano. Construction was begun on the set pieces on a soundstage in New Jersey by Macy’s Day Parade float makers Design Associates of New Jersey. Work was nearly completed when Elektra postponed the shows until February 1974 — before cancelling them altogether.

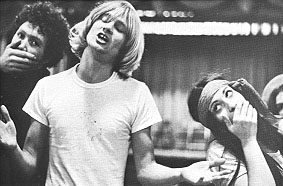

On 8 March, Jobriath and the Creatures of the Street appeared on The Midnight Special, taped from a performance in January where Jobriath, dressed in Stephen Sprouse outfit, shared a bill with the more down to earth Gordon Lightfoot and Richie Havens. Originally, the band had chosen the S&M-themed track, “Take Me I’m Yours,” which was rejected by the show’s producer and replaced by the more generic, Elton John-ish “Rock of Ages“; followed by Jobriath’s statement of purpose, “I’maman.” After taping was finished, a birthday party was held for Brandt. Although the full nature of Jobriath’s and Brandt’s relationship isn’t entirely known, when Brandt swanned in with heiress (and probable benefactor) Peggy Nestor on his arm, Jobriath supposedly smashed the cake in Brandt’s face.

In the UK, a bit of the Midnight Special footage was run on The Old Grey Whistle Test. After the album’s release there, the reviews were generally negative, including in Sounds and NME, the latter of which dismissed Jobriath as “the fag-end of glam rock.” Melody Maker, though, was less notably less hostile, describing him as a “true Renaissance man who will gain a tremendous following” with “talent to burn.”

Instead of an opera house, Jobriath and the Creatures of the Street’s live debut came with two sold-out shows at New York’s Bottom Line, playing to modest crowds of 400 on 24 and 25 July. Their next show was at the Nassau Coliseum, where they shared billing with Rufus. There, a hostile audience booed, taunted them as “faggots” and threw garbage before the band ran off-stage.

With glam rock fading and the debut selling poorly, Elektra nevertheless cobbled together a follow-up drawn from the same sessions as had produced the first record. Creatures of the Street (1974-Elektra) was released just six months after the debut and, comprised as it was of rejects from the debut, was less beholden to commercial considerations and also more varied, including the sublimely ridiculous “Dietrich/Fondyke (a Brief History of Movie Music)” and “What a Pretty,” the cod-country “Scumbag,” and straightforward gems like “Heartbeat,” “Street Corner Love,” and “Gone Tomorrow.” Whereas the debut had been hyped to high heaven, the silence surrounding the follow-up was deafening.

In the spring of 1975, the band embarked on a short but exhausting and stressful tour, beginning with a performance at the Troubadour. On the road, they indulged in phencyclidine, alcohol, methamphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, and groupies. One band member was arrested in Tennessee. Somehow, through the fog, the band occasionally booked time in various studios and recorded new tracks including “New York, New York,” “Girl of the Night,” “Weightless Love,” “You Little So and So” “Molière’s Misanthrope,” “Jobriath’s Symphony,” “No Need to Cry,” “The Actor Loves Himself,” “Lullaby,” and “Oh Lord, I’m Bored (Good Fight).” Halfway through the tour, Jobriath accused Brandt over the phone of sinking Creatures of the Streets’ advance in his next venture, the Erotic Circus. Brandt, in turn, ended their relationship. They never saw one another again and Brandt never managed another musician.

Elektra followed suit by dropping them. Nonetheless, the band toured on manager and label-less, still charging their expenses to the label. Perhaps surprisingly, at their final show at Alabama’s Tuscaloosa University on 20 September, they played five encores before the fire department ended their performance. Even as the band finally appeared to be living up to the hype, it was agreed that it was too little too late and the members went their separate ways. Jobriath announced his retirement from music and his intention to return to acting.

The separate members of the Creatures of the Street went on the various things. Gregg Diamond wrote Andrea True’s disco hit, “More, More, More” and formed Diamond Touch Productions. He wrote “Hot Butterfly” for Bionic Boogie and brought fellow Creatures Jim Gregory and Steve Love to TK Records where they played on his Starcruiser album. He died of gastrointestinal bleeding in 1999. Steve Love worked as a session musician with many artists. Hayden Wayne had recorded as a solo artist and at one point accompanied Nell Carter.

With no acting work coming his way, Jobriath moved to the Chelsea Hotel, ultimately taking up residence in the rooftop pyramid residence that had been Sarah Bernhardt’s. Meanwhile, he resumed hustling as well as performing ‘30s pop and cabaret as Cole Berlin in a restaurant, the Covenant Gardens. Cole Berlin appeared in a Nigel Finch documentary for the BBC’s Arena series about the residents of the Chelsea Hotel and he played a slightly demented Noel Coward-esque original, “Sunday Bruch.” It was supposedly the theme from a play he was working on about a tourist who comes to New York who is eaten alive. Still under a ten year contract, he still couldn’t, however, record his own material. Instead, Cole Berlin would play anything from “Stardust” to the theme from Star Wars… “anything except ‘Feelings‘.”

In January 1979, Omega One magazine featured an article, “Schizophrenia: The Two Faces of Jobriath.” When asked about Jobriath over the phone, Berlin claimed, “Jobriath committed suicide in a drug, alcohol and publicity overdose.” When interviewer Charles Hershberg came to Jobriath’s home, he was introduced instead to several new alter egos. Cole Berlin and Joby Johnson talked about themselves only in the third person. When asked again about Jobriath, Johnson replied, “Her? Do I have to talk about her?” and later suggested, “They used a mannequin’s ass for the poster, and it wasn’t as round as Jobriath’s. That’s probably why Jobriath didn’t make it.” To prove his point, he posed for photographer John Michael Cox Jr. in a series of nudes. After re-emerging once again with a new personality, Mr. Broadway told Hershberg about his new musical, Pop Star, about “hype …and America.”

In 1981, Campbell began suffering from recurring bouts of illness and lost a lot of weight. He turned to a macrobiotic diet and meditation but his illness persisted. Although frail, he nonetheless performed for the Chelsea Hotel’s 100 year anniversary in November 1982. Campbell then grew more reclusive and ultimately a hotel manager called the police after receiving no response. On 3 August 1983, the police broke into his apartment and found his lifeless body. They estimated he’d been dead for four days. In another statistical first, Jobriath was the first known AIDS casualty at The Chelsea.

By the 1980s, Jobriath’s growing cult included big names singers including Ann Magnuson, Gary Numan, Gavin Friday, Joe Elliot, Marc Almond, Mark Stewart, Neil Tennant, Morrissey, and Siouxsie Sioux. His long out-of-print records became collector’s items. In 1992, unaware of his passing, Morrissey attempted to secure Jobriath as an opener for his tour promoting the heavily glam-influenced Your Arsenal. In 1998’s Velvet Goldmine, an ill-fated glam rocker, Maxwell Demon, releases an album that looks very much like Jobriath. In 2004, Morrissey oversaw a Jobriath compilation, Lonely Planet Boy (Sanctuary), a well-chosen collection (largely eschewing his more run-of-the-mill rockers) which included “I Love a Good Fight” (aka “Oh Lord, I’m Bored (Good Fight)”). In 2007, both Jobriath albums were remastered and re-issued on CD byCollector’s Choice. Obscure band, Balcony, wrote a single, “Jobriath.” Perhaps nothing suggests how far we’ve come more than the fact that Def Leppard covered Jobriath’s “Heartbeat” for a Wal-mart exclusive.

UPDATE:

Since this piece was published, several key developments have occurred, enhancing Jobriath’s posthumous recognition. In 2012, the feature-length documentary Jobriath A.D.: The True Story of a Rock and Roll Fairy, directed by Kieran Turner, was released, which I saw at Don’t Knock the Rock — and ran into DJ Lance Rock. That same year, Ann Magnuson created a spoken-word album and performance piece, The Jobriath Medley: A Glam Rock Fairy Tale.

That was followed by the release of previously unheard music on several albums, including As the River Flows (2014) which featured early 1970s studio recordings, and Popstar: The Lost Musical (2015), containing music from his unrealized autobiographical stage show. In 2019, Morrissey covered “Morning Starship” for his 2019 covers album California Son.

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hey Freelancer!, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, the Los Angeles County Store, Sidewalking: Coming to Terms With Los Angeles, Skid Row Housing Trust, the 1650 Gallery, and Abundant Housing LA.

Brightwell has been featured as subject and/or guest in The Los Angeles Times, VICE, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, LA Times 404, Marketplace, Office Hours Live, L.A. Untangled, Spectrum News, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, Notebook on Cities and Culture, the Silver Lake History Collective, KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, All Valley Everything, Hear in LA, KPCC‘s How to LA, at Emerson College, and at the University of Southern California. He is the co-host of the podcast, Nobody Drives in LA.

Brightwell has written a haiku-inspired guidebook, Los Angeles Neighborhoods — From Academy Hill to Zamperini Field and All Points Between; and a self-guided walking tour of Silver Lake covering architecture, history, and culture, titled Silver Lake Walks. If you’re an interested literary agent or publisher, please reach out.

You can follow him on:

Bluesky, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, iNaturalist, Instagram, Letterboxd, Medium, Mubi, Substack, Threads, and TikTok.