This piece was originally written for “Ask Silver Lake.” “Ask Silver Lake” is dedicated to exploring the history and insights of our community. If you have questions or ideas you’d like us to consider, please drop a comment or send them to outreach@silverlakenc.org.

Silver Lake is home to several historic hilltop estates. A couple — Frank Garbutt‘s Garbutt House and Julian Eltinge‘s Villa Capistrano — have been covered in past editions of “Ask Silver Lake.” This month’s subject, the Crestmount estate, has an equally colorful hisotyr. Several readers requested more information about the historic property in light of recent rumors that a highly-regarded restaurant might be coming to the property. While I can’t substantiate those rumors nor add much on that speculative front, I can, at least, shed light on the lavish estate’s rich history

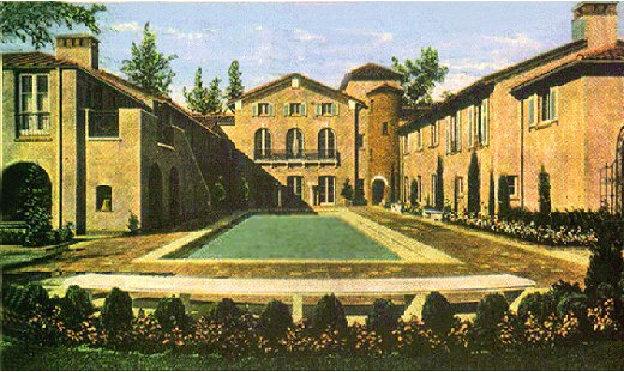

Crestmount is a sprawling estate situated atop the highest hill in Silver Lake. The designer of the Mediterranean Revival-style estate was Robert D. Farquhar, one of the foremost California architects of the early 20th century. Born in Brooklyn, Farquhar was educated at Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts. He established his own practice in Los Angeles in 1905. From his new home, he designed the Barlow Medical Library (1907), William Andrews Clark Memorial Library (1924–1926), Beverly Hills High School (1928), and The California Club (1930).

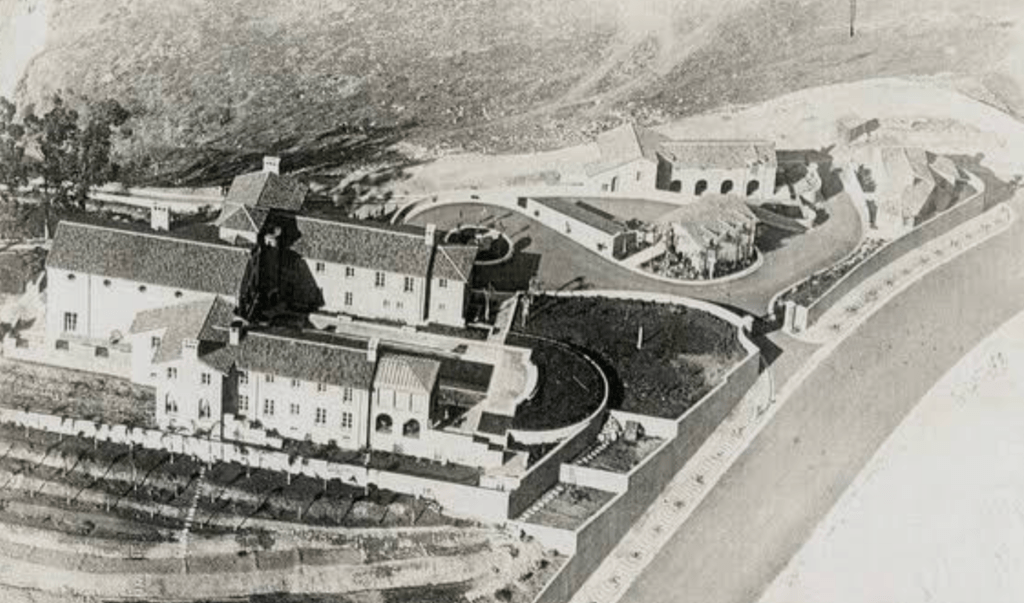

Farquhar was commissioned to design a large estate in 1918 that included not just a mansion — but stables and a tack house, an ice plant, a green house, three staff cottages, an orange grove, a rose garden, a swimming pool, and garages to accommodate five automobiles. Farquhar’s client was a 34-year-old socialite named Daisy Canfield, who was then married to Jay Morris Danziger. Danziger was then-vice president of the Mexican Petroleum Company – a company that had been co-founded by Edward Laurence Doheny and Daisy’s father, Charles Adelbert Canfield.

Daisy Emma Canfield was born in Nevada in 1884 to Chloe Phebe Wescott and Charles Canfield. Charles Canfield had made his fortune in New Mexico‘s silver mines. California’s oil fields would make him another fortune. When Daisy was eight years old, Charles Canfield and Doheny partnered to develop the first gusher in Los Angeles, in the then-posh neighborhood of Crown Hill, just west of Bunker Hill. The Canfields lived nearby in Westlake, at 8th and Alvarado.

In 1906, Chloe Canfield was murdered by Morris Buck. Buck was a disgruntled coachman who’d been fired by Charles five years earlier for supposedly beating and neglecting the Canfield’s horses. He’d recently asked for a loan from the Canfields and received no response. After shooting Chloe twice and fleeing; Buck was apprehended by a bicycle cop. He was tried, convicted, and ultimately hanged in 1907. Charles Canfield died in 1913, at the age of 65. His will left each of his five biological children, including Daisy, a fortune of one million dollars (over $33 million adjusted for inflation). Their adopted sister, Dorothy, received $250,000 (eight million in 2025 dollars). The will also stipulated that his heirs create a Chloe P. Canfield Memorial Home for girls “superior in intelligence and excellent in character”… and “of the Caucasian race.”

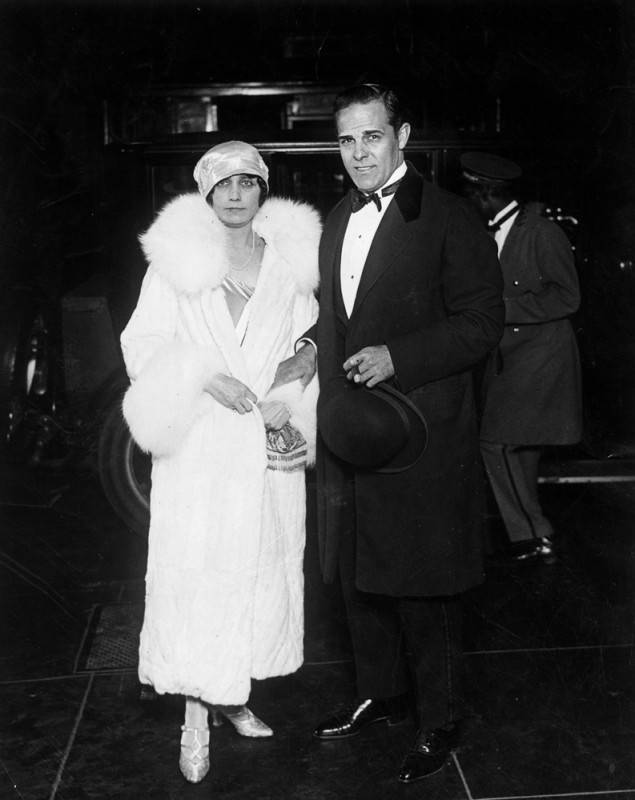

During her marriage to Danziger, Daisy had given birth to three children: Daisy “Dutch” Canfield Danziger (b. 1902), Elizabeth “Beth” Chloe Danziger (b. 1910), and Robert Jay Danziger (b. 1913). In December 1921, before Crestmount was completed, Daisy filed for a divorce from Danziger charges of cruelty. She pointed, specifically, to his affairs with two different women. Shortly after their divorce was finalized, Canfield married movie star Antonio Moreno. A Beverly Hills street that was to have been named Danziger Drive was, at Daisy’s insistence, instead named Moreno Drive. The rest of the streets in that neighborhood, meanwhile, were named to honor the men who ran the Beverly Hills Speedway (minus Danziger). By then, Moreno Drive in Silver Lake had already been named after Daisy’t new husband, as well.

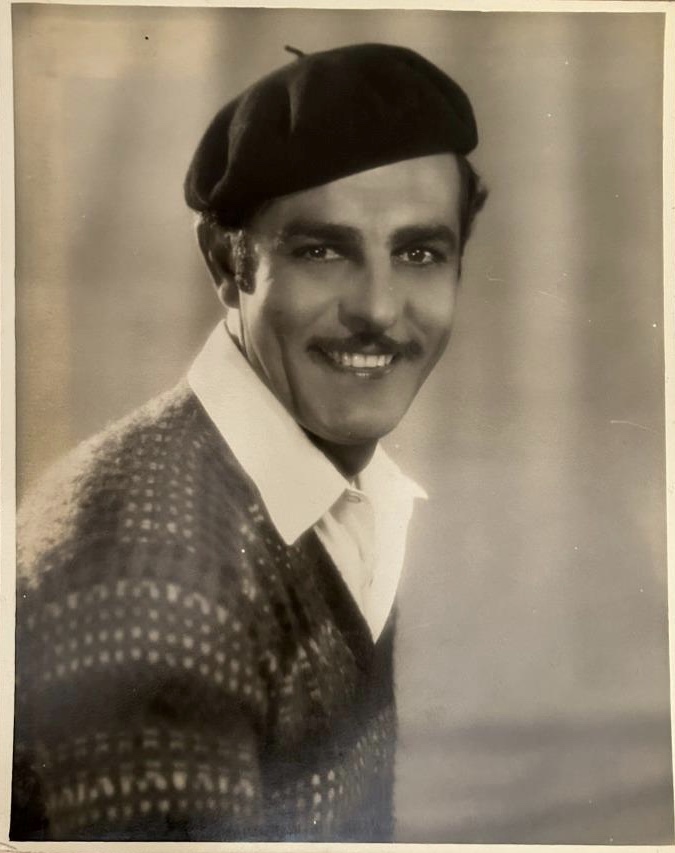

Moreno (né Antonio Garrido Monteagudo) was born in Madrid to an army officer and his homemaker wife. Antonio’s father died when he was a child and his mother relocated them to Algeciras, where they lived in the shadow of the ruins of ancient castles and fortifications. When he was about fourteen-years-old, Monteagudo emigrated to the US where he found work at a utility company in Northampton, Massachusetts. In 1912, Monteagudo moved to Los Angeles where he began appearing, as Antonio Moreno, in Hollywood films – mostly filmed for Biograph and Vitagraph studios.

On 1 February 1922, filmmaker William Desmond Taylor was murdered in a killing that was never solved. Moreno was rumored to have been in a romantic relationship with him. Reportedly worried about a probe into his private life, Moreno married the wealthy and recently-divorced Daisy Canfield on 27 January 1923. He also, that year, signed a contract with Famous Players–Lasky Corporation (later Paramount Pictures). Finally, construction of Crestmount was completed and, the following spring, the couple moved in. It was Canfield who’d commissioned the home and her money that paid funded its construction, Nevertheless, credit for building the estate was and continues to be misattributed to Moreno. In the 1920s, at least one reporter attempted to suggest that its creation was the fruition of Moreno’s childhood dream to live in a Spanish castle.

Crestmount wasn’t the only home on the hill for long. Canfield and Moreno subdivided the bulk of the property north of their estate as the Moreno Highlands, a subdivision they envisioned would resemble a rambling village nestled below their grand Spanish castle. A stroll through the Moreno Highlands today, though, reveals that this vision was quickly abandoned — despite many fine Mediterranean and Spanish Revival-style homes there. The Moreno Highlands Tract opened on 3 February 1924.

In 1929, Canfield first attempted to establish the Chloe P. Canfield Memorial Home in the long-vacant Los Terrados Hotel in South Pasadena. After she met resistance there, though, she instead offered her own home, Crestmount. The property was handed over to the Franciscan Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception. Daisy, meanwhile, went on a vacation to Europe. The Chloe P. Canfield Memorial Home formally opened on 9 April 1929 — Easter Sunday.

After Canfield returned to Los Angeles, she relocated to an Arthur Williams-designed Mediterranean Revival home in gated-Laughlin Park on Linwood Drive. There Daisy was joined by Moreno, two of her children from her previous marriage, and a professional woman from Nebraska named Alice Olivia Hoffmaster.

Moreno and Canfield had no children of their own. They separated in January 1933 and Moreno afterward moved into the Hollywood Athletic Club. Just a few weeks after her divorce, on 23 February, Daisy Canfield died when her car plunged from Mulholland Drive. It was driven by a family friend, René H. Dussag, who was uninjured but survived the fall. Moreno ultimately moved to Beverly Hills — a city co-founded by Daisy’s father. He never remarried and died there in 1967. Incidentally, Crestmount’s architect, Farquhar, died ten months later.

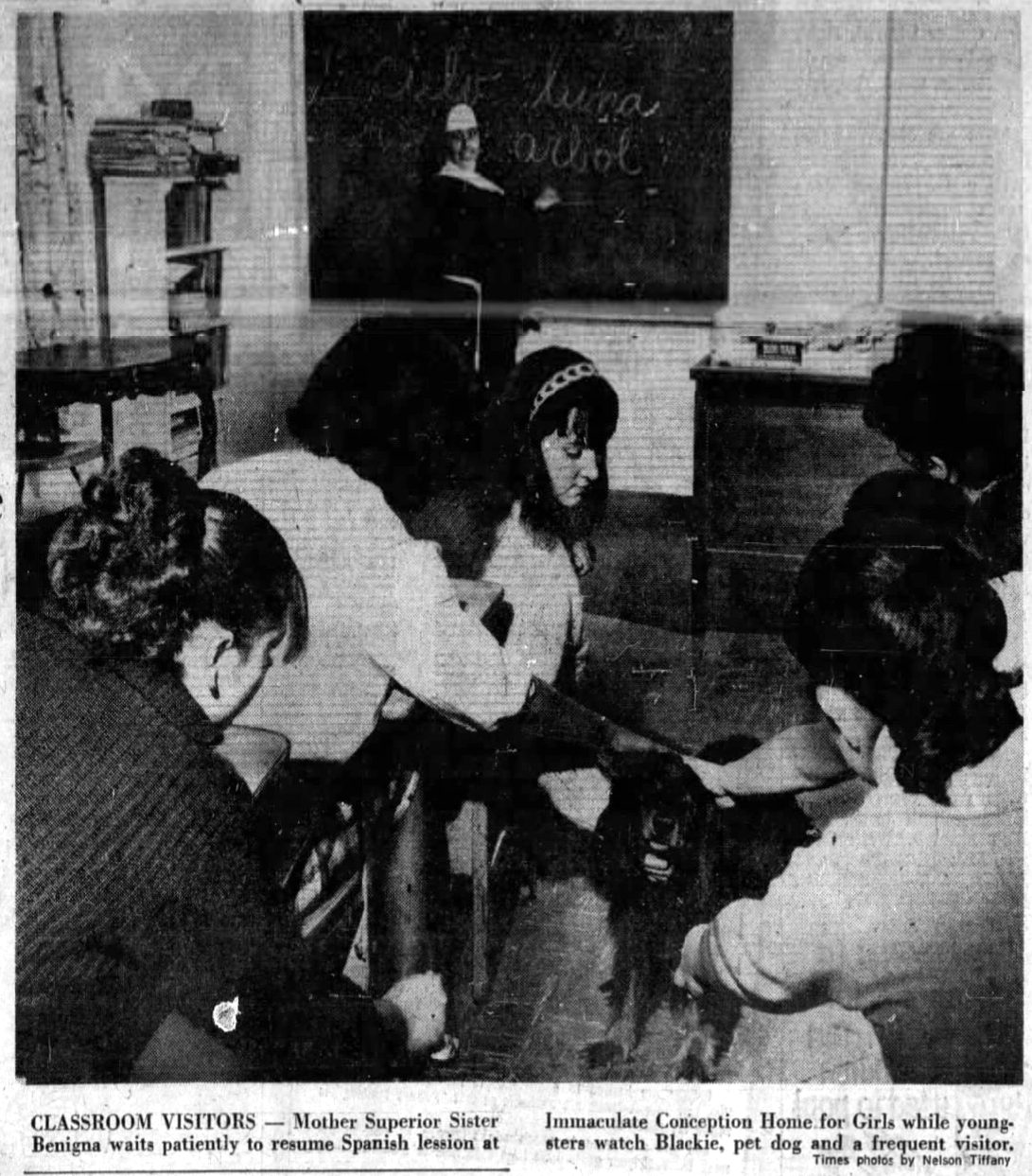

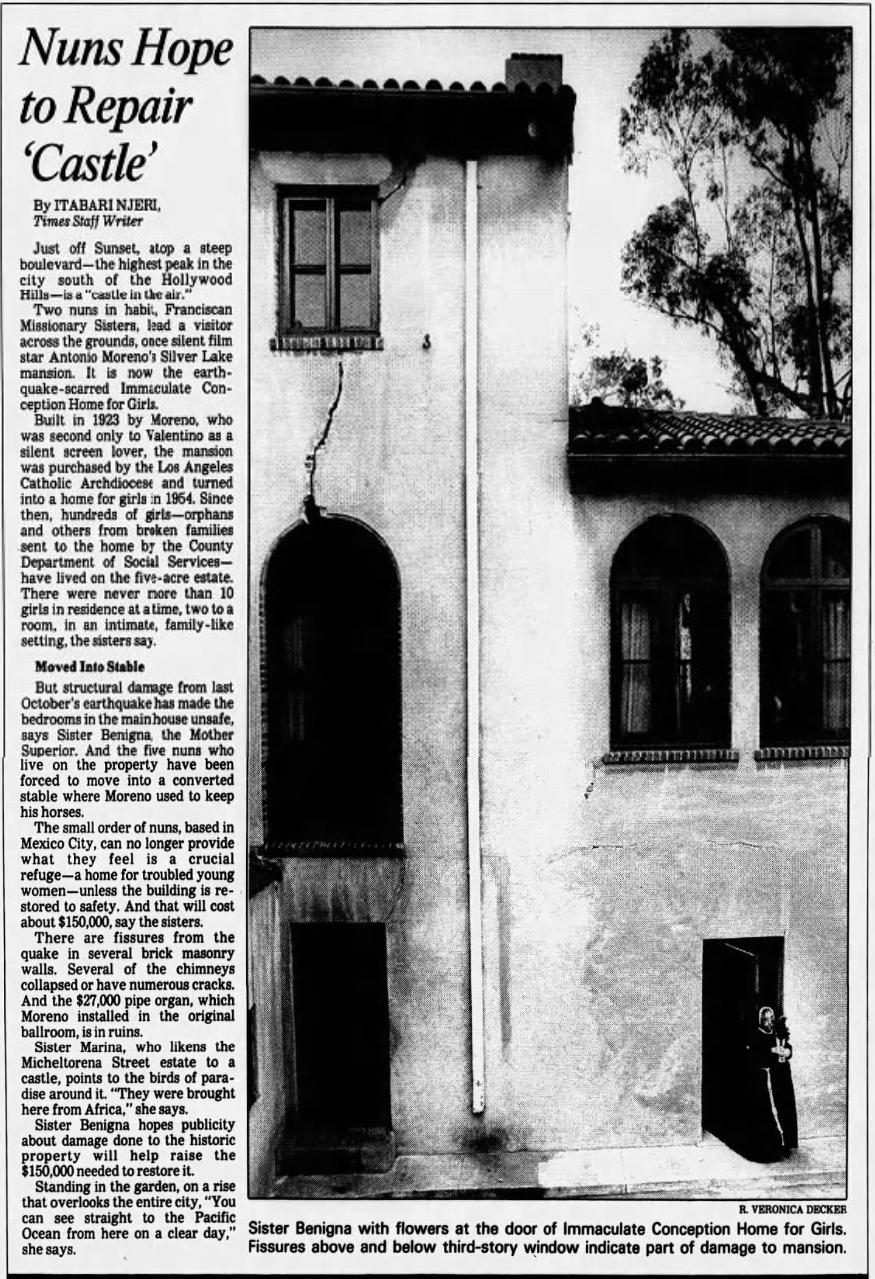

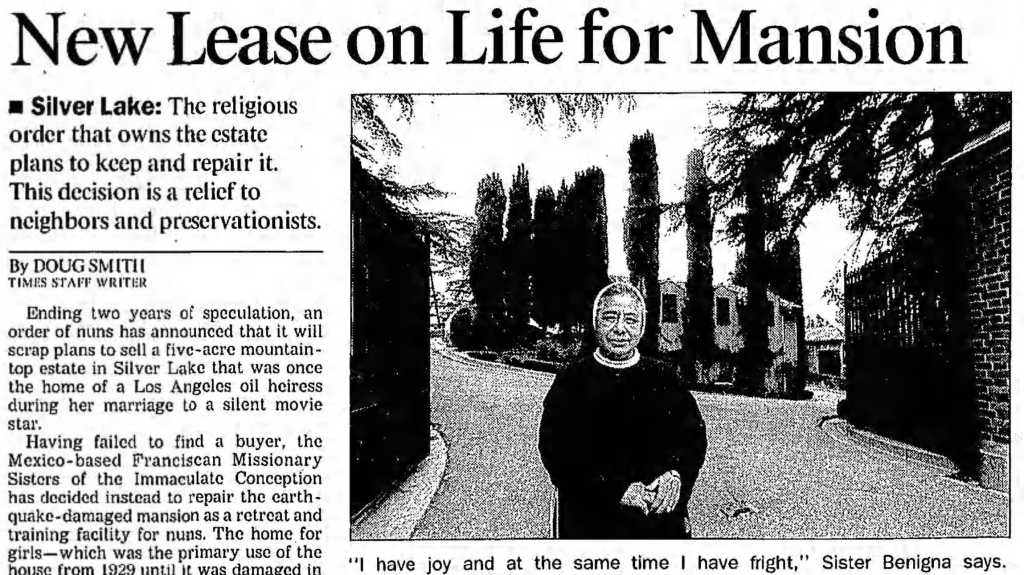

In 1953, the Chloe P. Canfield Memorial Home had been sold to the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, who transformed it into the Immaculate Conception Home for Girls. Fearing the former would frighten the girls, the nuns covered over a mosaic depicting Daisy Canfield with one depicting the Virgin Mary. The home remained in operation until large cracks appeared in the property following the Whittier Narrows Earthquake of 1 October 1987. At that point, the five nuns living there moved from the damaged main building into the stables. They also applied for it’s landmark status. On 4 October 1988, Crestmount (as “The Canfield-Moreno Estate”) was designated Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 391.

The nuns initially hoped to repair the property, which, in 1988, Sister Sandoval hoped would be turned into a sort of retirement home for nuns. In 1991, however, the nuns decided to sell the estate, attracting a few celebrity inquiries. Rick Rubin had a look around but rejected it as “too Shining. He reportedly suggested that Anthony Kiedis recommend it to Dana Hollister, whose clients then included Tim Burton, a filmmaker who one might reasonably expect would appreciate its somewhat gothic vibe. Hollister, though, fell in love with the property and dreamt of turning it into a boutique hotel called Hotel 1923. Her dreams were opposed by an angry mob of local neighbors and City Council District 4’s then-representative, John Ferraro.

At that time, Hollister was best known as an interior designer and owner of the showroom, Odalisque (an archaic term for a concubine). She came, though, to establish and/or renovate more than a dozen properties in Los Angeles, including Silver Lake’s Cliff’s Edge, the 4100, and Bethany Presbyterian Church. She finally acquired Crestmount in 1998 for $2.25 million and re-opened it as a boutique hotel called The Paramour (an archaic term for an illicit lover).

Under Hollister’s tenure, Crestmount was rented out for weddings, fund raisers, and as a filming location. It appeared in movies (The Cell (2000), Scream 3 (2000), and The Neon Demon (2016)); television series (Rock of Love: Charm School (2008), Charm School with Ricki Lake (2009), Monk (2009), and Another Period (2013-2018)); and music videos (R.E.M.’s “At My Most Beautiful” (1998), Shivaree’s “Goodnight Moon,” (1999), Britney Spears’s “My Prerogative” (2004), and Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds’ “If I Had a Gun” (2011)). In 2005 and 2006, the members of Papa Roach lived there whilst composing their album, The Paramour Sessions. They were followed by My Chemical Romance, who lived in the estate as they recorded their album, The Black Parade.

A decade later, Dana Hollister became embroiled in a multi-year legal battle over another historic property, the Earle C. Anthony Estate. That estate, like Crestmount, is a sprawling 1920s Spanish-Italian style estate in Mideast Los Angeles, designed by a École des Beaux-Arts-trained architect (in this case, Bernard Maybeck). Like Crestmount, it, too, was home to a group of nuns – the California Institute of the Sisters of the Most Holy and Immaculate Heart of the Blessed Virgin Mary. They had lived in compound since 1972 and wished to sell to Hollister.

In 2014, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles agreed to sell the estate to pop singer, Katy Perry, for $14.5 million. Hollister, though, struck a deal with the nuns to buy it for $15.5 million. A years-long legal battle ensued in which one of the nuns, Sister Catherine Rose Holzman, died in court during a post-judgement hearing. The sale fell through. On top of that, the jury found that that Hollister had “deliberately and maliciously” interfered with the pending sale and awarded $5 million in compensatory damages and $10 million in punitive damages to the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Los Angeles and Perry’s company, The Bird Nest LLC. In a settlement, however, the settlement amount was lowered to $6.5 million. Still a sizable sum, Hollister declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2018 and divested herself of several properties, including the Brite Spot, Bethany Presbyterian Church, Cliff’s Edge, the 4100, and Villain’s Tavern.

In March 2021, Hollister listed Crestmount for sale for $39.9 million. In November 2021, the asking price was lowered to $29.5 million after Hollister publicly alleged that Zillow’s “Zestimate” (which valued the property at around $5 million) had negatively impacted her chances of finding a buyer. Had it sold for that much, it would’ve still been by far the biggest real estate sale in the neighborhood. Its final sale price was not publicly disclosed but according to a mid-2025, real estate report, the most a home has ever fetched belongs to the Miller Fong-designed Memphis Milano-inspired estate at 1844 Silverwood Terrace, which was sold in June 2025 for $9.8 million.

In June 2023, Crestmount was acquired by Ken Fulk and his business partner, Clark Lyda, through their company, Fairview Partners. Meanwhile, on 1 July 2025 it was announced that René Redzepi‘s three-Michelin-starred restaurant, Noma, was planning a temporary five to six-month residency in Los Angeles sometime in 2026. On 18 July 2025, a Substack called Eastside Rag published a piece titled “SCOOP: Noma is coming to Silver Lake,” in which author John Fulton reported having heard from “a very reliable source” that the specific location would be Crestmount.

What will happen next, then, at the crest of Silver Lake’s highest mount? Will the walls of Crestmount find themselves breeched by selfie-snapping, Mar-a-Lago faced hordes? Will Micheltorena Street crumble to the sea beneath an endless stream of blacked-out, TCP numbered land yachts? Will Crestmount fall? Only time will tell – but it’s worth recognizing that in its first 100 years, Crestmount survived and endured divorce, reality television strivers, nuns, earthquakes, and perhaps, worse. Thus, this icon of Silver Lake seems likely to endure another century and remain comfortably situated in the pantheon of Silver Lake’s iconic hilltop fortresses.

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hey Freelancer!, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, the Los Angeles County Store, Sidewalking: Coming to Terms With Los Angeles, Skid Row Housing Trust, the 1650 Gallery, and Abundant Housing LA.

Brightwell has been featured as subject and/or guest in The Los Angeles Times, VICE, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, LA Times 404, Marketplace, Office Hours Live, L.A. Untangled, Spectrum News, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, Notebook on Cities and Culture, the Silver Lake History Collective, KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, All Valley Everything, Hear in LA, KPCC‘s How to LA, at Emerson College, and at the University of Southern California. He is the co-host of the podcast, Nobody Drives in LA.

Brightwell has written a haiku-inspired guidebook, Los Angeles Neighborhoods — From Academy Hill to Zamperini Field and All Points Between, that he hopes to have published. If you’re a literary agent or publisher, please contact him.

You can follow him on:

Bluesky, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, iNaturalist, Instagram, Letterboxd, Medium, Mubi, Threads, and TikTok.

One thought on “Ask Silver Lake – Crestmount”