INTRODUCTION

If, like me, you ride a bicycle in Los Angeles, there’s a good chance that you’ve heard of the fabled California Cycleway — an elevated, wooden bicycle tollway that existed for an all-too-brief moment at the dawn of the 20th Century — before the Age of the Automobile. The California Cycleway is legendary — and as with all legends, separating truth from fiction can be a challenge. Filling in the blanks requires conjecture and speculation. I’ve heard and read, for example, that the California Cycleway was the first bicycle highway, that its intended terminus was Union Station but that it only made it to the Raymond Hotel, that it was built by the former mayor of Pasadena, that there was a casino at its midpoint, and that it was killed by the car. None of that, it turns out, is true.

There were, in fact, earlier dedicated bicycle-only roads — although, not likely, elevated ones. Union Station wasn’t constructed for decades after the abandonment and dismantling of the cycleway. The cycleway’s creator was not Pasadena’s mayor but the former Chairman of its Board of Supervisors. The Raymond Hotel burned down five years before the cycleway opened — and only reopened after the Cycleway had closed. And as tempting as it is to blame all woes on the urban automobile and carbrain, it was actually interurban rail — specifically one railway magnate — that really put the brakes on the cycleway.

Legends also have a way of growing. I don’t remember exactly when it was, but years ago, at a party, I was chatting with some guy who insisted that the cycleway had, in fact, been completed. I tried to qualify that only a short section of it was built. He wouldn’t have it. He just kept insisting that it had been completed. Since there was no point in listening to him, I walked away… but I remained interested in the cycleway.

A few months ago, transit advocate Severin Martinez reached out the possibility of my making a map of the cyleway. He’d done a lot of work and research trying to figure out the cycleway’s path — both built and un-built — in preparation for a ride he’s leading tomorrow. Aided by his considerable research, here is my attempt to provide the fullest history of the California Cycleway yet published. If you have any additions or corrections, please let me know in the comments so that I can update this post and give you credit.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE BICYCLE

The earliest thing that most people would recognize as bicycle-like entered the picture in the early 19th century. Karl Drais’s Laufmaschine, mockingly referred to as the “dandy horse,” made its debut in 1817. Although almost entirely made of wood, it had a bicycle-like shape with two wheels, a seat, and handle bars. Unfortunately for riders, though, it had no brakes or pedals. it was basically bicycle for the Flinstones. More than half a century later, the slightly ridiculous high wheel bicycle appeared in 1871 wheeled into view. It was nicknamed the “penny-farthing” because of its wheels of vastly different sizes. It will be familiar to fans of the television show, The Prisoner, where a canopied version serves as the logo of the Village. It was also, for whatever reason, a popular tattoo in the 2010s. The first so-called safety bicycles appeared in 1876 but it was in 1885 that John Kemp Starley’s Rover became the first truly popular and practical bicycle. The design of bikes since then has change, to my eyes, comparatively little. In fact, I’d bet if you rode an 1885 Rover in 2023, you’d scarcely raise an eyebrow. It was the Rover, and other safety bicycles, that ignited, in the 1880s, a Bike Boom.

THE BIKE BOOM

People went mad for bicycles in the 1880s. In 1882, Arthur Hotchkiss built the Hotchkiss Bicycle Railroad, a pedal-powered monorail connecting Mount Holly and Smithville, New Jersey. In 1886, a banker from Los Angeles named S. G. Spier, rode a penny-farthing from New York City to San Francisco in 84 days — 49 years before a paved transcontinental highway would make such a journey even fathomable for most. By 1886, Pasadena had emerged as the bicycle capital of the world, with more bicycles per capita than any other city. Dedicated cycleways began to appear in the following decade.

The Coney Island Cycle Path opened in 1894. In 1896, bicycle shopowners Bob Lennie and Joseph Ostendorff successfully lobbied for the creation of the Santa Monica Cycle Path. It stretched all the way from Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery in Pico Heights to Santa Monica. Its route, I believe, later formed the basis for much of Washington and National boulevards. A writer of the day noted appreciatively that users of the bicycle road didn’t have to worry about frightening horses or farmers driving their cattle. Both seem quaint to me today, when my worries whilst cycling revolve entirely around antisocial drivers.

Organized cycling clubs emerged in Los Angeles in the 1890s. It was in or around 1896 that the Los Angeles Wheelmen formed — one of the region’s first bicycle clubs. Soon after, they were joined by the East Side Club (of Boyle Heights), The Wanderers (of Santa Monica), The Crown City Club (of Pasadena),and the Riverside Club (of Riverside). Such groups were instrumental in driving the Good Roads Movement, which sought to improve the deeply-rutted, dusty dirt roads (then the norm) with smooth, paved ones.

With better roads came longer rides. The first Century Run — a bicycle ride from Pomona to Santa Monica and back again — was won by Harry Cromwell. For years, a bike race took place between Santa Monica and Los Angeles every 4th of July. There was a race between Los Angeles and Riverside. There were relay races between Los Angeles and San Diego. At Agricultural Park (now Exposition Park), there were “piano races,” so known because winners of them often took home a piano as prize — albeit presumably not on their bikes. By 1900, there were fifteen bicycle shops in Pasadena alone — a town, then, of just 9,117 residents. Los Angeles ’s population,then, was 102,479. An estimate guess that, between the two cities, there were approximately 30,000 cyclists — or roughly 27% of their combined population. Not only was there the Bike Boom, though, there was also a boom in tourists — both cyclists and non-cyclists. Into this bike-crazed scene stepped a businessman named Horace Dobbins, who hoped to exploit the Bike Boom with a rather fanciful business proposition.

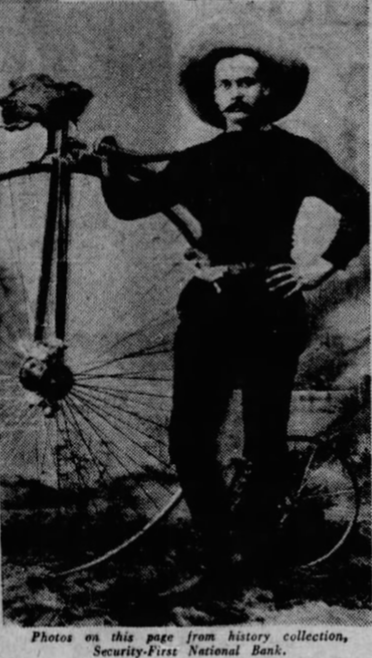

HORACE DOBBINS

Horace Muriel Dobbins had been born on 29 August 1868, in Philadelphia. He moved with his family moved to Pasadena one year after its incorporation, in 1887. As an adult, he had served as the vice president of the El Cajon Valley Company before becoming the Chairman of Pasadena’sBoard of Supervisors on 16 April 1900. He was not, himself, a cyclist. In fact, at least one source has claimed that he owned the first automobile in Pasadena — not that multi-modality wasn’t “a thing’” then. In 1900, most everyone both walked and rode trains. James F. Crank’s Los Angeles and San Gabriel Valley Railroad, which connected Los Angeles to Pasadena, began operation the year before the Dobbins family arrived in Pasadena. The Pasadena & Los Angeles Railway Company merged with the Los Angeles & Pacific Railway to create the Pasadena & Pacific Electric Railroad Company in 1895. Its motto, “from the mountains to the sea,” reflected its reach from the San Gabriel Valley to Santa Monica. That railway was owned by Henry Edwards Huntington — a real estate developer and collector of art and books. Huntington did very well for himself, living near Pasadena on a massive estate that is now “the Huntington,” or, The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens — if you’re not into the whole brevity thing.

DOBBINS’ VELOWAY

Horaces’ father was Philadelphia architect Richard James Dobson. When he died in 1893 at the age of 60, he left Horace an inheritance. Horace decided that what bike-crazed Pasadena and Los Angeles needed was an elevated cycleway connecting them. Toward that end, he secured a right-of-way, on 23 August 1897, between Pasadena’s then-new Hotel Green and a point in what would later be subdivided as the Montecito Park Tract. His business partners in the venture also included former California governor, Henry Harrison Markham, Ed Braley of Pasadena’s Braley Bicycle Emporium, and Professor Thaddeus Low — a balloonist who’d had a hand in the creation of the Pasadena and Mount Wilson Railway, a funicular train which ascended from Rubio Canyon to a resort on the summit of Echo Mountain (after Mount Wilson was ruled out). They applied for an application to construct the cycleway on the right-of-way. The California State Legislature rejected their application. They tried again in 1898 and, that time, were approved. Construction of the cycleway began in November 1899.

Although called the California Cycleway, Dobbins claimed that it would be open to “bicycles and other horseless vehicles.” It was also billed as “the only toll road catering exclusively to two-wheelers.” So — any and all two-wheeled vehicles that were horseless? I suppose, then, that Dobbins might have been OK with motorcycles (which had been invented in 1885) and electric bikes (which had been invented in 1895) — provided the rider was willing and able to lug one them the cycleway’s stairways. There were no elevators on the cycleway.

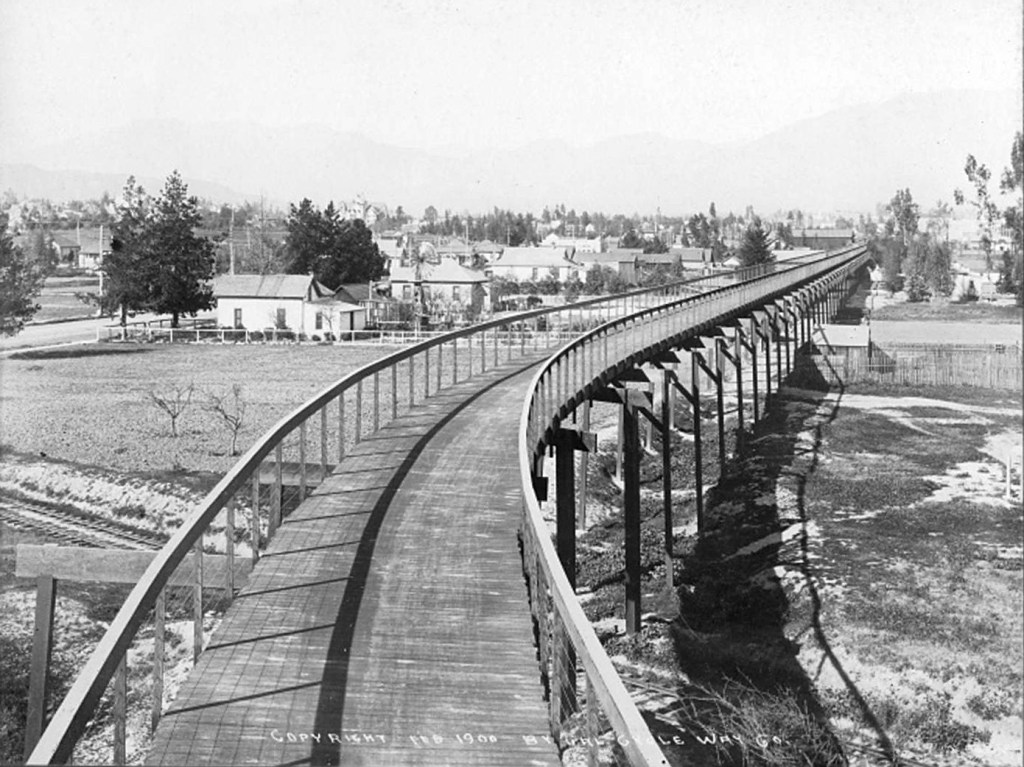

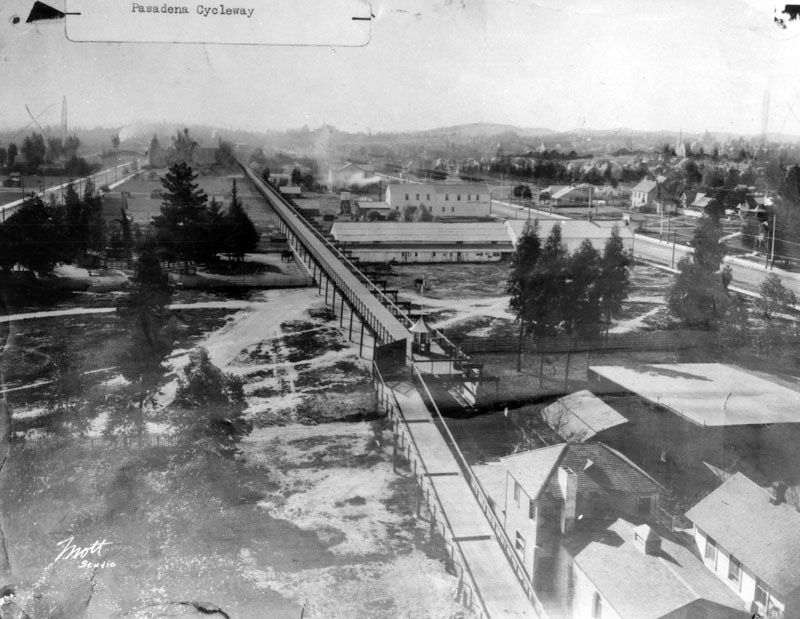

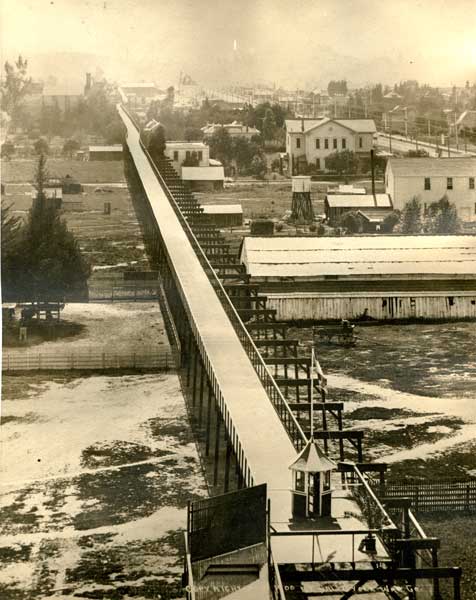

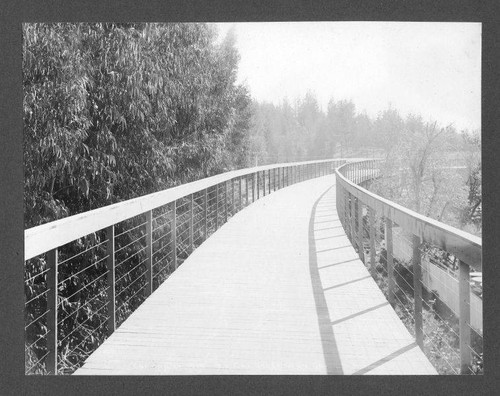

When completed, the cycleway would be fourteen kilometers long. At its steepest, its grade would be 3%. Its average grade would be just 1%. The cycleway was 2.4 meters wide. At its maximum elevation, it was fifteen meters high — traversing a 30.5 meter wide right-of-way. In other spots, it would barely be elevated at all. The cost of a one-way ticket was ten cents ($3.66 in 2023). A round-trip was fifteen cents ($5.48 today). It would be lit, for nighttime rides, with incandescent lamps. At its midway point, there would be a resort called the Merlemont Casino, which was to have even included a “Swiss dairy.” The total cost was projected to be $200,000 (about $7.3 million in 2023).

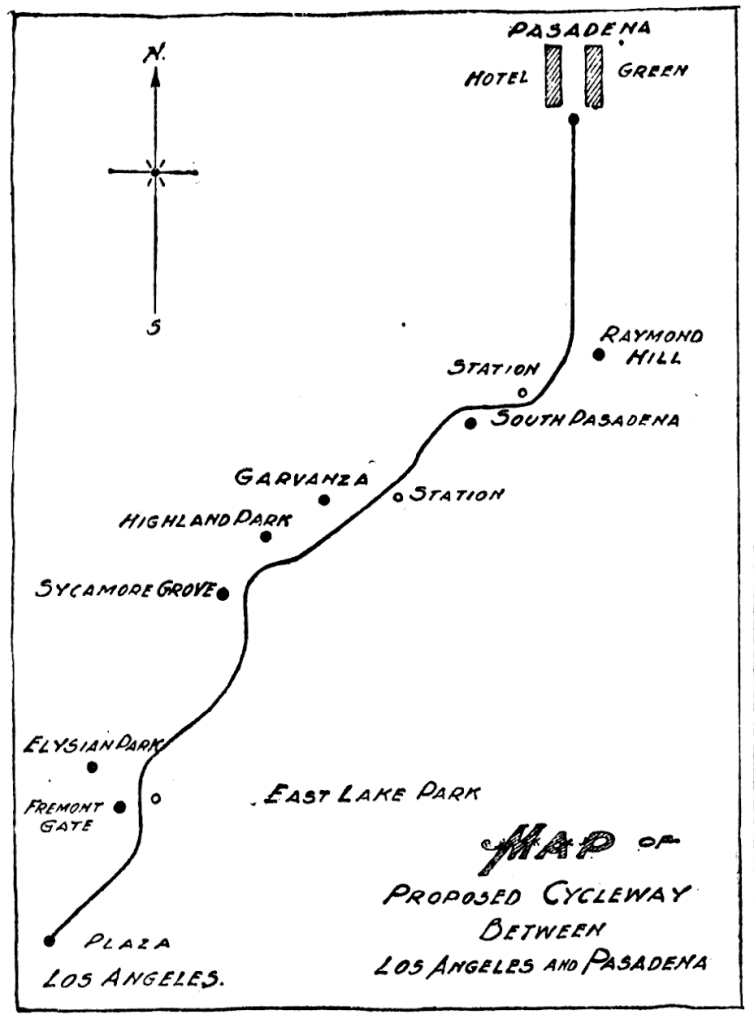

The Cycleway’s route, after passing through South Pasadena, was to have closely followed the course of the Arroyo Seco. Since Dobbins never secured the right-of-way between what’s now Montecito Heights and Downtown Los Angeles, it was subject to change. In 1898, The Los Angeles Herald wrote that, at Avenue 35, the “cycle path will cross Pasadena Avenue on another high bridge and follow the Terminal and Santa Fe Railway down Los Angeles river on its way to the terminus at the plaza in this city. Elsewhere, it was written that the cycleway would cross the Los Angeles Rriver south of Buena Vista Street (now Broadway). By the 1930s, Dobbins claimed that it would have tunneled through Elysian Park. His right-of-way ended near the intersection of East Avenue 35 and Griffin Avenue (near the modern-day location of Heritage Square Museum) so I suppose he could imagine any route he wanted between there and El Pueblo that he wanted — but it would’ve probably involved a lot of negotiating with municipal and transit agencies. The endpoint — with all descriptions — was to have been the Plaza de Los Ángeles.

The first shipment of Oregon pine arrived in San Pedro via a schooner, the Letitia, in September 1899. A second load arrived from Puget Sound on 15 October. A third shipment arrived later that month. The lumber was supplied by the Patton and Davies Lumber Company of Pasadena, and was stored near a railway siding in a lot on Glenarm Street, where construction began with Enginer W. R. Stevenson overseeing the installation of concrete piers by a crew of fifteen. A shipment of nails arrived on 7 November 1899. Yes, a shipment of nails was the sort of thing covered in the newspapers of the day — as far away, at least, as San Francisco. By 9 December, the frame of the first section was almost entirely in place and installation of the cycleway’s floor began. It was painted green.

THE OPENING

The first 2.1 kilometers of the California Cycleway opened at 8:30 on 1 January 1900. The first passengers were a flock of thirteen, led by Revered Otis Bedell. A reporter for The Los Angeles Herald noted that “nearly 1,000 people took advantage of the first opportunity ever offered to spin down an elevated path, whirling above the housetops and through the branches of trees, avoiding dust and danger of collision with horses and men.” . The dawn of a new century must’ve struck Dobbins with an optimistic note. I doubt, at least, that he’d have predicted that it would close before the end of the year.

THE CLOSING

After its opening, i could find no further accounts of the cycleway until ten months later, by which time there had apparently been no further construction. The Raymond Hotel was then in the process of being rebuilt after a devastating fire had closed it years earlier. It seems that the novelty of riding a bicycle from Hotel Green to the husk of another hotel on an elevated cycleway had already faded. If a cyclist wished to ride between the two hotels, for whatever reason, they could do so without paying a fare and carrying their bike up and down staircases merely by heading south on Fair Oaks Avenue — a ride that, unlike the cycleway, would carry them past numerous amenities. For most cyclists, a ride underneath shade trees is preferable to a ride above them. On 8 October, The Pasadena Daily Star reported that construction on the cycleway had ceased. Dobbins remarked to The Los Angeles Times, “I have concluded that we are a little ahead of time on this cycleway. Wheelmen have not evidenced enough interest in it…” On top of that, the Bike Boom had bust. The California Cycleway was closed.

Many accounts of the Cycleway’s closure, written much later, pointed the blame at the car. Cars, after all, are the culprits in most transit crimes — but not, seemingly, in this case. I say this, primarily, because there just weren’t many cars then. Of course, there were a few. Cars had been a reality in Los Angeles since 1897, when S.D. Sturgis and J. Philip Erie drove their noisy motor carriage along a few blocks of Downtown Los Angeles before it broke down. Cars, naturally, were slow to catch on in cities. They’re loud, foul, inefficient, expensive, dangerous, and require lots of space to store them when they’re not in use — which is the vast majority of their existence. Why — with Los Angles’s weather — and a network of more efficient alternatives — would anyone want a “stink chariot?”

Back then, the car capital of the US was Des Moines — the capital of the rural and hopelessly car-dependent state of Iowa. I lived in Iowa in the 1990s and — when I lived there— I had a car. In the Iowa countryside, there are not mass transit options. I used to get off work from Hardee’s in the wee hours of the morning and then undertake a long drive in subzero temperatures along frozen interstates and gravel roads. On the farm, we had to lug feed to hog lots, load those fattened hogs for slaughter, transport bails of straw, and perform other tasks that even the biggest cargo bike wouldn’t have been up to.

The Metro Los Angeles commuter of 1900 had more options. The Los Angeles Pacific Railroad, The Pasadena & Los Angeles Electric Railway, Southern Pacific Railway, Temple Street Cable Railway Company, and other companies all operated passenger rail networks of various sizes. Dozens more were in the works. A few years earlier, Frederick Blechynden filmed an “animated photography” on South Spring Street — the first “motion picture” shot in Los Angeles. The 25-second long film is captioned, by the Edison Film Company, “Various equipages pass, including a tally-ho and six white horses. A peculiar, open-end trolley car comes along; bicycle riders and pedestrians.”

AFTER THE CYCLEWAY’S OVER

In March 1901, it was reported that Pasadena was going to built its Central Park at the cycleway’s northern end. Pasadena City Council stated, that November, that allowing the cycleway to pass through the park was “out of the question. Dobbins, they claimed, had been franchised to build a cycleway all the way to Los Angeles — and since he’d failed to go beyond even South Pasadena, his franchise was likely to be forfeited. On the 10th of the month, Henry Huntington merged several railways to create the Pacific Electric Railway of California — in the process creating the largest electric interurban rail network in the world — an no city served by it would have a greater density of coverage than Pasadena. In December, Dobbins agreed to relinquish his right to the northern end of his cycleway for $3,750.

Huntington had also thrown up a roadblock in the south. In 1901, he began planning a “Bridge of Sighs” for the trains of his then-planned Pasadena-Los Angeles Short Line across what was meant to be the path of the California Cycleway, at Raymond Hill. The two parties settled in 1902 but the construction on the Cycleway would not resume. Things weren’t exactly looking up. In May, the company’s bookkeeper, Captain James A. Stafford, died of pneumonia. Dobbins told Pasadena’s City Council that he wasn’t ready to abandon the project yet. It they could just donate him a new lot, he could build a new entrance after the section at Central Park was demolished in December. The second Raymond Hotel, opened on 19 December 1901. But now there was no entrance or exit at Hotel Green. The beautiful Raymond Hotel would close during the Great Depression and was razed.

By 1904, there were still only 1,600 motor vehicles registered in Los Angeles — or roughly one car per 130 Angelenos. Per capita car ownership in Pasadena was even less — further proof that neither Angelenos nor Pasadenans had yet surrendered themselves to car dependency. That January, the cycleway was utterly abandoned but Robbins held on to most of his right-of-way. Dobbins denied the rumor that he intended “to use his right of way for a mono-railway—or its is so remotely in the future that it isn’t worth talking about.” Lots began to be carved from the undeveloped right-of-way in 1905, however, as land seized through eminent domain was returned to residents. As for the abandoned cycleway, it had already fallen into disrepair. Reverend Robert J. Burdette described it as a ruin to rival those found in Italy. A newspaper article termed it the “objectionable cycleway.” The California Cycleway company listed a steel bridge as “for sale” in 1907. That October, Dobbins petitioned Pasadena to remove the cycleway from his right-of-way.

Dobbins had a new plan for his property. In 1909, he founded the Pasadena Rapid Transit Company, which absorbed the California Cycleway Company. Fifteen investors in the latter were given stock in the former and Dobbins was the company’s president. Dobbins again made a grand claim. In 1897, he’d claimed that the California Cycleway would be completed within two years — and only a very short section of that had come to fruition. Now he claimed he would build a railway that would tunnel through Elysian Park and terminate near Central Park (now Pershing Square), in the heart of Downtown Los Angeles. And it would be completed in even less time. Dobbins issued a letter addressed to the people of Los Angeles, in which he wrote, The Pasadena Rapid Transit railroad to Los Angeles will be built and it is my honest belief that this road will be built and the cars running between Pasadena and Los Angeles inside of eighteen months.”

Three years passed and there was still no train. In 1912, Dobbins planned to sell the Pasadena Rapid Transit Company to a firm in Antwerp, but it fell through.

On 20 February 1917, Dobbins sold the Pasadena portion of his right-of-way to the city for $156,425. That same year, Pasadenans voted on a measure to build a municipal electric railway line on the right-of-way. It was narrowly defeated after Huntington promised to improve Pacific Electric service. The city afterward began converting sections of the right-of-way into streets and alleys. Many remaining its of the right-of-way began to be sold and developed in the 1950s.

DOBBINS’S LATER LIFE

Although Dobbins hadn’t completed either of his planned transit projects, he remained a prominent Pasadenan for many years. He joined the Pasadena Board of Trade and the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. He served as president of the Pasadena Board of Health, and then, the Pasadena Hospital Association. He moved back to Philadelphia in 1932 where he managed the Broadwood Hotel. After he retired, he spent much of his time and fortune sailing yachts. He sailed to his new home, Charleston, in 1947. By 1958, he was living in San Pedro. That year, he was a speaker at the 50th anniversary of the Pasadena Pioneer Association.

Dobbins died on 21 September 1962. His obituary in The Pasadena Independent included a mention of the cycleway. “Mr. Dobbins was president of the California Cycleway and the Pasadena Rapid Transit Co., which was instrumental in establishing methods of transportation between los Angeles and Pasadena in the early days. The mention seems to have been the first in a while, and renewed interest, and maybe planted the notion in people’s heads that either company had actually connected Los Angeles and Pasadena — which, of course, they had not. A few years later, in May 1963, a reporter at The South Pasadena Review wrote of the cycleway, “It is reported by Frank Stoney that the last of the installation was removed from the vicinity of the Raymond Hotel within recent years.”

TRANSIT LEGACY

By the 1920s, bicycling was seen as such a quaint relic of a different era, that a group of aging cyclists formed a group called Wheelmen of the Last Century. Dobbins’s old partner, Henry Markham, died at his home in Pasadena on 9 October 1923. Dobbins’s old foe, Henry Huntington, died on 23 May 1927. Pacific Electric, though, would chug along until 1965.

A second Bike Boom occurred from around that time. Seven million bicycles were sold in the US in 1970. Most were children’s bikes and many Americans, consequently, came to think of bikes as toys rather than transportation. Still, more bikes than cars were sold in the US during the years of 1972-1974. In 1983, the County of Los Angeles built the Arroyo Seco Bike Path between York Street Bridge and the Montecito Heights Community Center. A plan to extend it, in 2005, was withdrawn because people by then were less in favor of pouring more concrete on rivers. The Arroyo Seco Foundation developed the Arroyo Seco Greenway Project, which sounds a lot better with calls for paths and riparian landscaping — although I’m not sure what, or if, there’s a timeline for that.

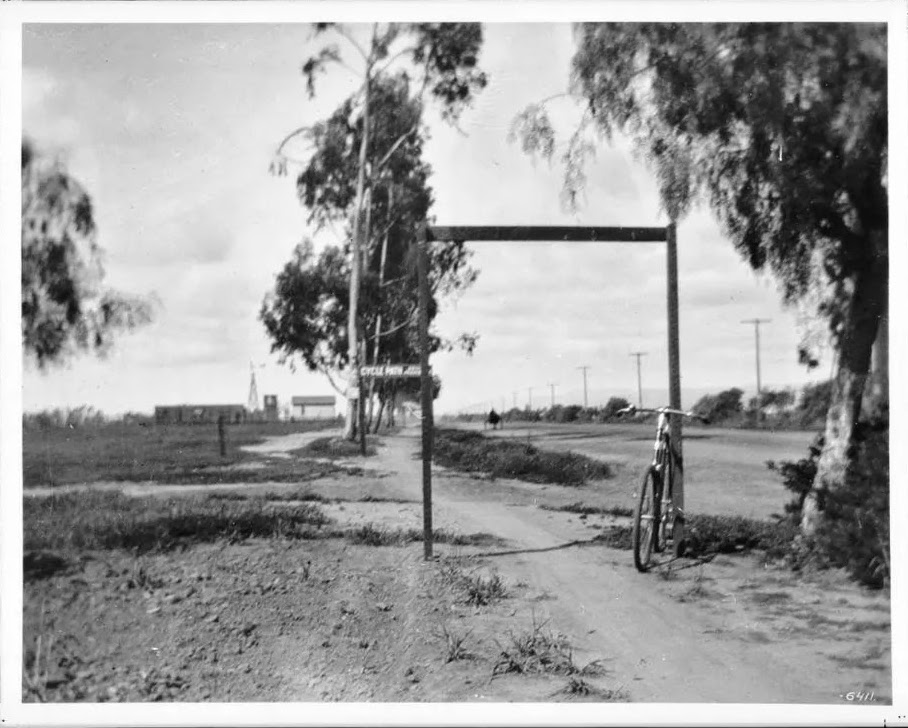

1990, Pasadena Mayor Jess Hughston formed a task force, the Mayor’s Committee to Make Pasadena Bicycle Friendly, in order to make Pasadena bicycle friendly. The task force’s Dennis Crowley, a construction manager from San Gabriel, re-incorporated the California Cycleway Corporation with the dream of realizing Dobbins’s vision — albeit this time with electronic tollbooths, call boxes, and ride-thrus. He said it could be built for $10 million. He got the blessing of Pasadena, South Pasadena, and Los Angeles’s governments. He got the backing of the Arroyo Verdugo Subregion — a consortium of five cities. Metro — the chief funders of bikeways — turned him down. Perhaps because they, like Huntington before them, had a different project in mind. On 26 July 2003, Metro’s Gold Line (now part of the A Line) opened, connecting Los Angeles, South Pasadena, and Pasadena by light rail. Dennis Crowley died in 2008.

THE CYCLEWAY’S LEGACY

The first Figueroa Tunnels would open in November 1931, opening a route to automobiles that Dobbins had sought to open to trains and — perhaps — bicycles. The southern tunnel opened on 4 August 1936. Construction of the Arroyo Seco Parkway began in 1938 and the tunnels became part of that. Although sometimes referred to as the first freeway, surely the Long Island Motor Parkway, which opened in 1908, deserves the dubious distinction of being the first dedicated, automobile-only highway. Its Arroyo Seco-adjacent route and dedication to a single transportation mode is like a distorted echo of vision Dobbins’s a bikes-only highway.

The Arroyo Seco Parkway was, when it opened on 30 December 1940, was quite unlike modern freeways. The speed limit was 45 miles per hour (72 kilometers per hour). Some of its off/on ramps had speed limits of 5 mph. It was deliberately curvy. Driving it was supposed to be fun. The fun stopped in 1954, when it was “upgraded” to the Pasadena Freeway. “Fun” isn’t a word many would use, today, to describe the process of being in a car on any inner-city freeway — where the view is usually of a ribbon of red brake lights.

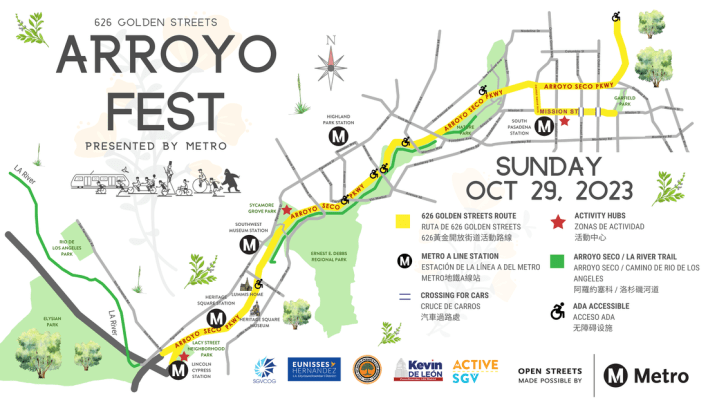

In 2003, the freeway got considerably less freeway like, temporarily, when it was shut down for ArroyoFest — the first open streets even in Los Angeles. For a few hours, cyclists and pedestrians got to walk along the former parkway. Its name reverted to Arroyo Seco Parkway in 2010. 626 Golden Streets: ArroyoFest (ArroyoFest II) was scheduled for 2020 but was scuppered by the COVID-19 Pandemic. It’s now rescheduled to take place on 29 October, between 7:00 and 14:00. It’s truly last minute, but Abundant Housing LA and Pasadena Complete Streets Coalition are hosting a ride along the old cycleway route called Remnants Ride: Retracing the Forgotten Cycleway from Pasadena to LA. It’s scheduled to take place tomorrow, on 14 October 2023, at 9:30.

AFTERWARD

Today, complete streets are generally preferred over grade separated, mode-specific transit-ways. It warms my heart knowing we’ll never open another freeway in Los Angeles and I look forward to the day interstates are reserved for connecting states and not carving through neighborhoods. When I ride my bicycle, I want to ride past restaurants, markets, libraries, parks, bars, theaters, cinemas, bookstores, coffee shops — and pop in and out of them as the mood moves me. That said, there is an appeal novelty transit amenities.

Paris’s Coulée verte René-Dumont and Seoul’s Seoullo 7017 are attractions more than they are transit routes — and they are attractive. In Los Angeles; people drive great distances for the pleasure of riding or just looking at Angels Flight, Disneyland Railroad, Getty Tram, Ghost Town & Calico Railroad, Los Angeles Streamers, Southern California Live Steamers, Travel Town Railroad, Venice Canals, the Trolley at The Americana at Brand. Can you blame them? They’re impractical but fun. And so, I still think it would be cool to build the California Cycleway, even if it wouldn’t be especially practical. And, for, let’s say, just $5 million, I’ll get it built within six months. Just cross my palm with silver (donate on Patreon) and I’ll let you know when I’m done.

FURTHER READING

“Railroad Issue Up Again” The Los Angeles Times (1920)

“In the Days of the Iron Steed” by Audrey Henderson Cooke (The Los Angeles Times, 1930)

“Horace Dobbins, Builder of Unique ‘L’, Now Retired” (Metropolitan Pasadena Star-News, 1947)

“‘Grandad’ of the Freeway” by C. F. Schoop (Independent Star News, 1958)

“Pedaling His Bikeway Plan” by Susan Moffat (Los Angeles Times, 1995)

“Bikeway Was Ahead of It’s Time” by Cecilia Rasmussen (L.A. Unconventional, 1998)

“Bicycles” (California’s Gold, 2004)

“Remembering The Great California Cycleway” (HighlandPark 2010)

“California Cycleway was scuppered by cars (street-cars, that is, not motor-cars)” by Carlton Reid (2013)

Cycleway” by Dan Koeppel (LAttitudes, 2015)

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hey Freelancer!, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, the Los Angeles County Store, Sidewalking: Coming to Terms With Los Angeles, Skid Row Housing Trust, and the 1650 Gallery.

Brightwell has been featured as subject and/or guest in The Los Angeles Times, VICE, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, Office Hours Live, L.A. Untangled, Spectrum News, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, Notebook on Cities and Culture, the Silver Lake History Collective, KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, at Emerson College, and the University of Southern California.

Brightwell is currently writing a book about Los Angeles.

You can follow him on Ameba, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, iNaturalist, Instagram, Mastodon, Medium, Mubi, the StoryGraph, TikTok, and Twitter.

Everybody drives in L.A. Eric, even ones that shouldn’t be. Way too many cars!!!

LikeLike

Gre

LikeLike

Fascinating. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person