I’ve been a fan of science-fiction ever since I was a toddler. Well, to be more precise, I was more of a fan of a certain sort of space opera than proper science-fiction. I wasn’t exactly reading Stanislaw Lem at that age. Lem has his spaceships but nearly enough shiny robots or laser battles to sustain my interest at that age, I’m afraid.

I still love robots and will pretty much give anything with one in it at least a chance. To my mind, with the possible exception of Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, who designed the stunning Maschinenmensch for Fritz Lang‘s Metropolis, no one was more influential in the design of robots in fiction than Robert Kinoshita, who was born in Los Angeles on this day in 1914, which seems like a nice opportunity to pay tribute and respect to him.

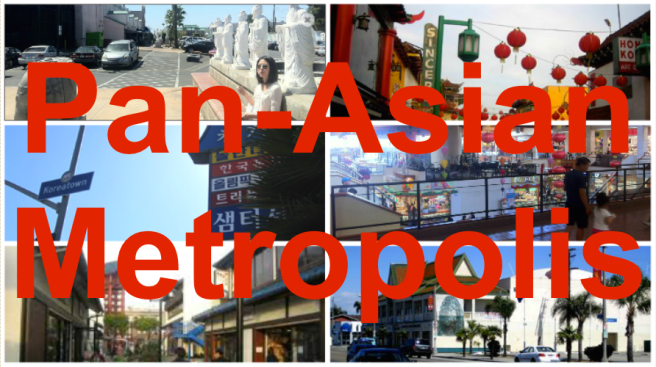

Robert Kazuo Kinoshita was born to Yasoichi Thomas and Helen Hatsue Kinoshita on 24 February 1914. He grew up in Boyle Heights, which until World War II was home to a large population of Japanese Angelenos. There he attended Maryknoll Japanese Catholic School in Little Tokyo. He graduated from Theodore Roosevelt High School. After graduation he worked (un-credited) as a production designer for 1937’s 100 Men and a Girl, a Depression Era comedy starring Deanna Durbin and, although I haven’t seen, almost certainly featuring zero robots.

Around that time, Kinoshita enrolled at the University of Southern California, from which he graduated in 1940 with a degree in architecture and minors in industrial design and ceramics. After school, he worked at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. In January 1942, Republican Fetcher Bowron began using his position as mayor of Los Angeles to demand Japanese American be sent to forced labor camps. He demanded that all Japanese American employees of the city be terminated from their jobs and claimed that Japanese American DWP employees like Kinoshita were likely to poison the water supply of Los Angeles out of a secret loyalty to the Japanese Emperor.

Shortly before they were sent to the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona, Kinoshita and his girlfriend, Lillian Fumiko Matsuyama, were married. The Kinoshitas were allowed to leave the concentration camp in 1945, when a couple in Milwaukee, Wisconsin agreed to sponsor them. There, Kinoshita worked for the Cleaver Brooks Company, designing industrial washing machines for the US armed forces and working with plastics — skills that would influence his subsequent robot designs. Lillian gave birth to two children, Patricia Lynne and Terry Glenn. The Kinoshita family returned to Los Angeles.

Back in Los Angeles — home to the largest population of Japanese in the US — the Kinoshitas faced hostility and Robert found it difficult to find employment. A sympathetic friend, Jack T. Collis, helped Kinoshita get hired as a set designer and art director at Ziv Studios. Ziv was a pioneer of syndicated radio programming that had, in 1948, launched a syndicated television company, Ziv Television.

In 1953, Kinoshita designed a robot for the DuMont Television Network‘s television series, Captain Video and His Video Rangers, filmed in New York City. The robot’s name was Tobor, or “robot” backward. Tobor’s name was accidentally applied backward, it was explained in the plot of “I, Robot,” written by none other than Isaac Asimov. Tobor was a tall robot and inside of him, appropriately, was 23-centimeter tall actor Dave Ballard. When Tobor returned in the episode, “Tobor’s Return” (also known as “The Return of Tobor”), he became the first recurring robot in a science fiction program. In 1964, a Boogaloo dancer in Oakland named John Murphy created a dance based on Tobor’s movements called the Robot. It would go on to be one of the key breakdancing moves of the hip-hop culture that arose in the 1970s.

With the aforementioned exception of Metropolis’s Maschinenmensch, previous films, serials, and television robots usually resembled mail collection boxes with accordion-like appendages. They inevitable lumbered stiffly and lacked any discernible personality. Tobor, whilst hardly limber, at least had a face and thus, at least the superficial suggestion of intelligence. Someone, apparently, thought he had what it took to carry his own film, which he did the following year.

The immodestly named Tobor the Great debuted on the big screen in 1954. On the titillating poster, a monstrous, red-eyed Tobor carries an unconscious woman in his arms. Her dress conforms to her body like cling wrap. The poster does not depict any scene in the film, however, which is aimed squarely at the prepubescent set. In fact, Tobor is created by a kindly old man and his best friend is a little boy. The villains of the film are more terrifying than a towering robot, though, they’re Communists! It should come as no surprise that, despite its title, it is not great, nor is it even especially memorable — although Tobor does make more of a lasting impression than his human counterparts.

As Kinoshita’s designs go, however, it’s easily his most conventional — looking rather like a suit of armor or a more menacing version of Frank Baum‘s Tin Woodman. Tobor’s career in Hollywood was not long, lasting just three years. A pilot for a proposed children’s series, Here Comes Tobor, was produced by Guild Films in 1956 but was not picked up. Guild made another successful attempt in 1957 but by then there was a new Kinoshita robot star.

Kinoshita’s next robot is, with respect to Tobor, one of the true greats and surely one of the most recognized robots in film history, Robby the Robot. Yet again, Robby’s name seems to be a play on the word, “robot,” which may’ve still seemed novel a mere 36 years after it was first coined. Of course, “Robby” is also the diminutive form of Kinoshita’s given name. Robby made his debut in Forbidden Planet (1956). Like Tobor before him, Robby is depicted in the film’s poster carrying an unconscious woman in a body-clinging dress and, as with Tobor the Great, no such scene takes place in the film. Unlike Tobor, however, the robot is obviously designed to hide the fact that a human actor is inside.

Robby’s arms steam strangely positioned and where one might expect an actor’s head is a clear dome-enclosed motor with moving parts that only hints at a face. Inside of Robby was Frankie Darro, a small-of-stature stuntman of just 160 centimeters. Robby was not the first robot with a clear dome. Before him were the Mark 1 from the little-remembered British comedy, Mother Riley Meets the Vampire, and Chani from 1954’s Devil Girl from Mars — although neither are anywhere nearly as iconic as Robby. Robby’s characterization and a vaguely bitchy polyglot seems surely to have been an inspiration on androids like C-3P0 from Star Wars, REM from Logan’s Run, and Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation.

Forbidden Planet is, itself, a groundbreaking film. Louis & Bebe Barron’s electronic score is a film first. The United Planets starship C-57D is the first faster-than-light ship in film and an obvious influence on Star Trek, although Gene Roddenberry had the foresight to envision a multi-ethnic future. In Forbidden Planet’s 23rd century, Robby is apparently the only non-Caucasian. Reasonably successful at the box office, it nevertheless made a star of Robby, who went on to appear in at least 29 other films and television programs, including The Thin Man, The Addams Family, The Twilight Zone, Lost in Space, Columbo, Ark II, Space Academy, Wonder Woman, Mork & Mindy, and Gremlins — to name only the appearances I remember him from. Robby was inducted into the Robot Hall of Fame in 2004. Now in his 65th year, he shows no obvious interest in retirement, having most recently appeared on an episode of Big Bang Theory.

Kinoshita’s next great robot was his first with a name that wasn’t a play on the word “robot.” Kinoshita referred to him as “Blinky.” His full name, stated only once, was Series 1A-1998 Class YM-3 Model B-9 General Utility Non-Theorizing Environmental Control Robotic Bion (or “1A1998YM3B-9 G.U.N.T.E.R.”). To his crew-mates on the Jupiter 2 and audiences of Lost In Space, however, he was almost always referred to simply as “the Robot.” A contest was held in which participants could suggest a name but none of the entries were chosen.

Kinoshita was in the work pool of 20th Century Fox’s art department in the mid-1960s when producer Irwin Allen tapped him to become the first-season art director for his then-new series, Lost In Space (1965-1968). Even people like me, who didn’t grow up watching the series, were familiar with the B9’s catchphrases, “It does not compute” and “Danger, Will Robinson!” That the Robot and Robby were designed by the same person is immediately evident. Like Robby, the Robot has a sort of plexiglass bubble-head which rises above a barrel chest and awkwardly protruding pincer-tipped arms. His lower half, though, is odd. The original articulated legs cut the legs of actor Bob May so the legs were bolted together and the Robot was pulled along by a string. Robby and the Robot even appeared together in the episodes “War of the Robots” and “Condemned of Space.”

The Robot was popular, inspiring, like Robby, toys, models, trading cars, and full-sized replicas built by adult men. The members of the Robot’s fan organization, the B9 Robot Builders Club, have built more than 100 full-size replicas. He also had a career that outlasted his original feature, albeit one less robust than Robby’s. In 1977-1978, the Robot appeared on Mystery Island as P.O.P.S. — a fussy robot with vast intelligence and the ability to speak many languages.

By the late 1970s, however, clunky tin-men with bubble-heads seemed less like inventions from the future than they did relics of the past. After all, real industrial robots had begun placing human autoworkers as far back as 1961 and malevolent computers like Alpha-60 and HAL-9000 had, by and large, replaced tottering tin-men in thoughtful science-fiction. Androids like those in Westworld and Alien were barely distinguishable from humans unless they were torn apart to reveal wires and fluids inside. Old-fashioned stiff, metallic robots were relegated to kid-friendly space operas and series like Doctor Who, Battlestar Galactica, The Black Hole, Starcrash, Jason of Star Command, Star Odyssey, and Buck Rogers in the 25th Century. Japan was a notable exception, where freed from the limitations prop departments, animators created nimble robots capable of flying and even transforming.

Kinoshita had by then long put his robot-designing days behind him. After Lost in Space ended its run, Kinoshita mostly worked as an art director in non-science-fiction television series, including Hawaii Five-O, Kojak, and Barnaby Jones. In 1976, he worked as a production designer and extra on a film that must’ve been close to home, Farewell to Manzanar (1976). His final work, before retiring in 1984, was on Glen A. Larson‘s forgotten series, Cover Up.

Kinoshita enjoyed a long retirement, attributing his fitness to clean living and daily consumption of vinegar. The Kinoshitas lived in Torrance together until Lillian died in 2002. In 2006, Robert appeared as himself in two short documentaries, Amazing! Exploring the Far Reaches of Forbidden Planet and Robby the Robot: Engineering a Sci-Fi Icon. Kinoshita bowled regularly at Gardena bowl until he suffered a stroke in 2009. He died at the age of 100 on 9 December 2014. He was survived, at the time, by children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, great-great-grandchildren, and of course robots who will outlast us all.

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, Los Angeles County Store, the book Sidewalking, Skid Row Housing Trust, and 1650 Gallery. Brightwell has been featured as subject in The Los Angeles Times, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, and on Notebook on Cities and Culture. He has been a guest speaker on KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, at Emerson College, and the University of Southern California.

Brightwell is currently writing a book about Los Angeles and you can follow him on Ameba, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Mubi, and Twitter.

Bob Kinoshita only co-designed and co-built both Robby and The Robinson Robot. Irving Block and several others contributed to Robby and Bob Steward did likewise with B9.

BTW – The phrase ‘YM-3’ for B9 was never mentioned in the show. It was used on a Japanese toy from the company AHI. Even more bizarre however, was the name ‘Friday Robot’ used on the Japanese plastic model kit by Marusan. Presumably the Japanese saw a connection between ‘Robinson Crusoe’ and the Robinson family!

Phil Heaton LISA-Lost in Space Australia

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the clarification. I’ll make corrections soon.

LikeLike