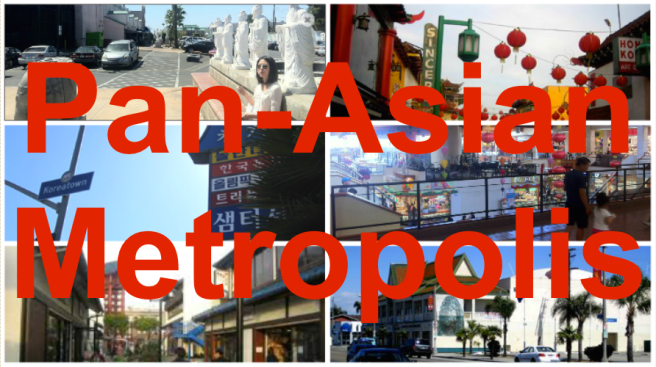

INTRODUCTION

Most of my essays about Los Angeles begin similarly. A question is asked, an answer is hard to find or is deemed inadequate, and then I head straight down a rabbit hole. This one began when a friend asked a question that involved Altadena and a street there with a Japanese name. She then mentioned that neighboring Pasadena had had a couple of Latino colonias — Chihuahuita and Sonoratown — both of which were new to me. This revelation led me to wonder whether or not Pasadena had ever had a Chinatown. Had it had one, it shouldn’t have been too much of a surprise. There are many lost Chinatowns. In 2018, I wrote “Orange County’s Lost Chinatowns” about the historic Chinatowns of Anaheim, Orange, and Santa Ana. I also, clearly, didn’t know about all of Los Angeles County’s vanished ethnic enclaves, either. I searched up “Pasadena Chinatown” and — internet searches not being what they used too — I got a whole lot of irrelevant results… but there were a couple of articles that confirmed my suspicion. And then I spied a white rabbit checking his pocket watch and down I went.

BEFORE CHINATOWN AND PASADENA’S BLACK FRIDAY

I found very little online that had been written about Pasadena’s early Chinese community — but what I did was written by Tim Greyhaven for his website, The No Place Project, and historian Matt Hormann. Both of them wrote about a night of violence that resulted in Pasadena’s Chinese being driven out of town. I’m deeply appreciative to both of them for their accounts. I couldn’t find anything, though, about the Chinatown that these excluded Chinese founded afterward — and which persisted from 1885 until it seemingly faded out of existence in the late 1930s. I couldn’t find any images whatsoever but I thought it was too interesting and too under-documented not to delve deep and share what I learned.

Mrs of Pasadena’s early Chinese came to work on the railroads. Most were peasants from Guangdong or Fujian. After the railroads were built, many found work as domestic workers, laundry operators and, especially, as cooks employed by hospitals, wealthy families, and in hotels. Most practiced Taoism and revered Guan Yu. Christian missions arose to convert them to Methodism. Most of the Chinese didn’t plan on staying in this often hostile state. They just wanted to make enough money to raise their station when they ultimately returned to their homeland.

The first Chinese-owned business in Pasadena was a laundry established on South Orange Grove Boulevard by Yuen Kee in 1875. In 1883, he relocated to Mills Street — now Mills Place. There, Kee rented a fifty square meter building from a trustee of the Pasadena Presbyterian Church named Jacob Hisey. Kee was followed by Lin Kee, who worked as a court interpreter. Still in 1883, a writer at The Pasadena Chronicle described this as a “Chinese Quarter.” Almost everything else I’ve read, though, suggests that there weren’t homogenous enclaves in this area and that the district’s population was a heterogenous mix of blacks, Irish, Italians, Japanese, Mexicans, Swedes, and others. It was the Chinese, though, that were seemingly singled out for abuse.

Anti-Chinese Violence was rife in California. In 1871, nineteen Chinese in Los Angeles’s Chinatown were lynched and mutilated. In the 1880s, there were massacres, riots, and expulsions of Chinese took place in at least 34 cities and towns. In Pasadena, the town’s only newspaper, The Pasadena & Valley Union, was amongst the loudest mouthpieces for anti-Chinese racists. A petition was circulated amongst the gentry calling on them not to rent to Chinese. Its signees included Pasadena’s first mayor, Martin H. Weight, fellow-future Pasadena mayor Theodore Parker Lukens (for whom the highest point in Los Angeles is named), and other prominent figures.

The petition was disseminated on 6 November 1885. Later that day, a group of 100 or so white Pasadenans gathered outside of Yuen Kee’s laundry. One, identified by the Chinese as Charley Johnson, threw a rock through a window and knocked over a kerosene lamp, which resulted in the laundry catching on fire. Kee escaped out of the back door and was pursued by members of the mob whilst others looted his burning business. According to Chinese witnesses, members of the mob chanted “lynch the Chinks” and “hang the yellow devils.”

Deputy Sheriff Thomas Banbury arrived on the scene and made clear that he would shoot anyone who continued to engage in criminality on the spot. The next day, however, an effigy of a Chinese man was lynched and hung from a telegraph pole. Making matters worse, the city of Pasadena passed an ordinance that stated “…it is the sentiment of this community that no Chinese quarters be allowed within the following limits of Pasadena: Orange Grove and Lake avenues, California St. and Mountain Avenue.” Chinese were then given 24 hours to vacate the area. The relocated to a short stretch of Pico Street that, from what I’ve seen, was the first and only community in Pasadena to have been referred to as its Chinatown.

A plaque that marking the site of laundry was placed there by Pasadena Heritage as part of an effort to highlight and create a sense of place with Pasadena’s charming alleys. It stated:

Named for Alexander Fraser Mills, a nurseryman who planted a citrus grove on 7 ½ acres at the northwest corner of Colorado Boulevard and Fair Oaks Avenue in 1878. Mills Place was originally named ‘Ward Alley.’ In 1885, a fire at this site destroyed a laundry establishment owned by Chinese settlers.

In early 2024, the plaque was replaced with with less passively worded text that centered the Chinese community:

Dedicated to the memory of Yuen Kee laundry and the early Chinese settlers of Pasadena who helped build railroads, labored on the citrus and grape farms and established successful businesses. On November 6, 1885, a mob threw stones into the laundry, breaking a kerosene lamp that burned the building down. The next day, the city barred all Chinese immigrants from living in the central portion of the city.

PASADENA’S CHINATOWN

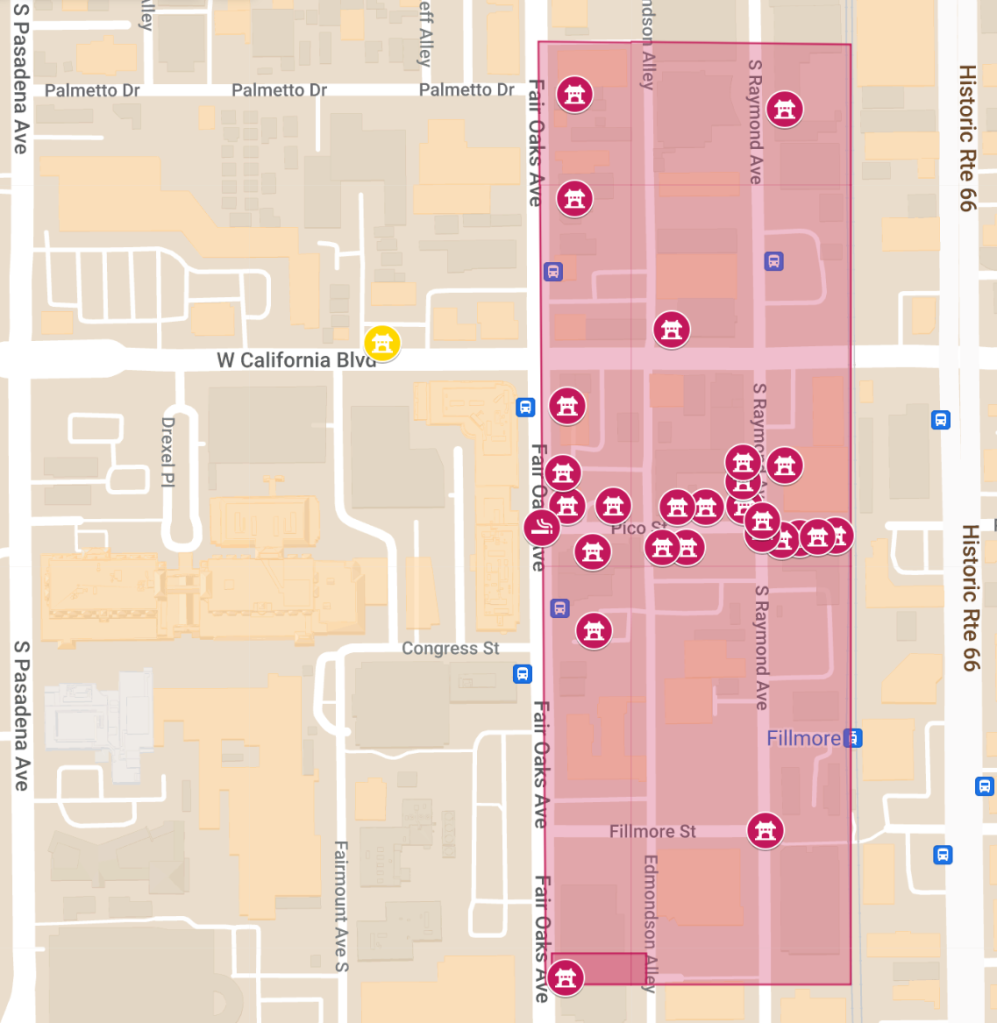

Most of Pasadena’s exiled Chinese relocated to a short street of San Pascual Street (later renamed Pico Street), then part of the larger Mexican enclave of Sonoratown. When Pasadena was incorporated as a city on 18 June 1886, Chinatown was located within it. There were Chinese homes along Fair Oaks and Raymond avenues, too. Edmondson Alley, which bisects Pasadena’s historic Chinatown, was — from 1897 until 1917 — the right-of-way for Horace Dobbin’s never-completed California Cycleway — an elevated bicycle tollway that was supposed to connect Pasadena to Downtown Los Angeles but only got as far as South Pasadena thanks to machinations from Henry Huntington. On the eastern edge of the neighborhood was the right-of-way used by the California Southern Railroad‘s Santa Fe Line.

The earliest reference I found to the enclave as Pasadena appeared in The Los Angeles Times in 1892, when a columnist wrote:

Much has been said recently about the unwholesome state of affairs in Pasadena’s Chinatown. Vice in its lowest forms flourishes while the sanitary condition of the place is filthy beyond description. The atmosphere on a close day is unpleasantly odorous. Few Caucasians care to penetrate the interior mysteries of the house of the Mongolian, the exterior surroundings hinting too strongly of the worse state of affairs that exist within.

It goes on to suggest that whites should boycott Chinese businesses and manages to slander one Leow Sing, “a Chinaman of rather an unsavory reputation,” for supposedly stealing chickens. And, although the writer acknowledges that there have been no reported cases of leprosy in Pasadena’s Chinatown, they mention that sometimes there are outbreaks of leprosy in Chinatowns. The Los Angeles Times was still harping about Pasaden’s Chinatown in 1901, when an anonymous columnist there wrote “Pasadena’s Chinatown has been ordered to ‘clean up.’ If the slant-eyed Celestials would ‘clean out,’ it would probably be much more appreciated at the ‘Crown of the Valley.'”

From then on, newspaper accounts of the community were almost exclusively limited to reports of raids on gambling houses and opium dens. The names of those arrested are nearly always printed — but the verdicts almost never follow. Although both gambling and opium smoking were and remain crimes, neither are violent ones. Neither, either, are that surprising to me. The passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 ended most Chinese immigration and bans on interracial marriage in California were only lifted in 1948. The result was a population of almost entirely male Chinese, excluded from meaningfully participating in the civic life of their city, and legally prevented from forming relationships with nearly all women in the city. So some of them, not surprisingly, spent some of their idle hours smoking, drinking, and gambling.

WING LEE — “KING” OF THE BING KONG TONG

Aside from gambling and opium raids, the papers were only interested in Chinatown’s tongs. Tong (堂) means “hall” and refers to closed organizations that serve Chinese communities by providing services like classes and counseling. Some also offer protection and other criminal services. The most notorious tong member in Pasadena’s Chinatown was Wing Lee.

A QUICK NOTE ON CHINESE NAMES

It is hard to research Chinese Pasadenans and Angelenos for several reasons. For starters, there are often multiple people with the same name and, when age is given, it becomes clear that there were multiple men named Wing Lee living in Southern California. Names, too, are often given as “Ah,” which is actually a prefix that makes a given name informal. “Ah Jim,” in other words, essentially means “Jimmy.” The family names are often ignored. At other times, the family name is listed first (as is the custom in China and for most people in the world) and at other times second (the custom in the US). Chinese characters are also romanized with various systems like pinyin and with inconsistent spellings. Finally, some Chinese were sometimes referred to by their Chinese names (e.g. Wong Bing Quong) and at other times by their “American” names (e.g. Frank Wong).

The most notorious Wing Lee as apparently a laundryman. His notoriety, however, stemmed from his role as a leader of the local Bing Kong Tong (秉公堂). The Hop Sing (合勝堂) and Suey Sing Tong (萃勝工商會) allied with one another to oppose the Bing Kong Tong in the Tong Wars. The precipitating event in the Los Angeles Chinese Massacre of 1871 had been a deadly shoot-out between members of the Hong Chow and Nin Yung tongs.

It’s difficult to say with certainty that it’s the same Wing Lee but on 1 December 1893, seven people at Wing Lee’s laundry were robbed by a group of two masked men carrying revolvers. Lee and another man were beaten when they failed to dig up a supposed buried stash of money. On 7 July 1894, a Pasadena man named Wing Lee was robbed of $5.50 at gunpoint as he stood at the intersection of California and Fair Oaks. The mugger shot Lee in the thigh. Identified as Wong Sing Sue, he was cleared of playing the lottery that August. In 1911, a Pasadena man named Wing Lee was struck in the head after delivering laundry and robbed at his laundry at 971 South Raymond.

On 27 March 1921, five tong members were arrested when the notorious Wing Lee requested police protection from members of the the Hop Sing Tong who’d driven over from Sacramento in order to murder him. Lee Wing (also reported as Louee Wing), Lee Poy, O. W. Kow, and Yung Pong were picked up near Wing Lee’s residence with concealed weapons. Also arrested was Low Gow, who was wanted for murder in Sacramento.

My suspicion is that the Wing Lee who was robbed so many times is the same as the Wing Lee of Bing Kong. Pasadena’s Chinese community was small — numbering somewhere between 60 and 100. A laundryman who’s been repeatedly mugged and shot might reasonably have turned to a Tong for protection and subsequently moved up the ranks. Laundromats, too, were often also apparently the sites of illegal lottery operations.

THE BIZARRE CASE OF GEORGE INGALLS AND LIM FOON

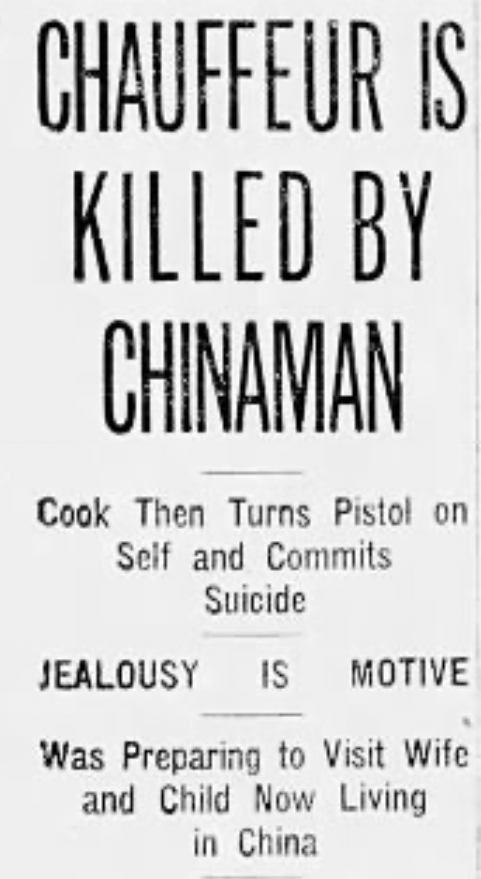

There was a very strange crime in 1911 in which Wing Lee was only tangentially involved. That September, the wife of Clayton H. Harvey called the Pasadena Police to report the murder of her family’s chauffeur, George R. Ingalls, by her family’s cook, Lim Foon. When the police arrived at their home in posh Bellefontaine, next to Chinatown (where Lim Foon lived on Pico Street) they found the lifeless body not just of the chauffeur, which lay in the home’s reception room — but also the lifeless body of Lim Foon. His corpse lay partially under the bed in his quarters. Bullets had apparently been fired from a Colt .38 through a mirror, into the ceiling, and into Lim Foon’s head. Ms. Harvey had a gun, too, which she had been carrying because she claimed she thought she’d heard burglars and had gone to investigate — only to encounter Lim Foon, who shot the chauffeur in front of her before she ran upstairs to call the police.

Lim Foon was estimated to have been about 25 years old and had been in Los Angeles earlier that day to pick up his passport so that he could voyage to China to visit his wife and child there. For reasons not explained in the newspaper accounts, it was Wing Lee who called Lim Foon’s uncle and cousin in Los Angeles to inform them about the death of their young relative. Given the strange and violent circumstances, Lim Foon’s family requested an inquest. They were denied The Pasadena Police determined that it was a clear “out-and-out case of murder and suicide” and that the motive for a murder-suicide had merely been Lim Foon’s — set to return to China to be reunited his his family — was driven insane with jealously of Garvey “usurping his place as a household favorite.” The Pasadena Post noted concluded that “…an explanation of the shots fired through the looking glass and the walls of his room, will probably never be made.”

A week after Lim Foon’s death, on 15 September, Wing Lee and Wong Hen were arrested for gambling out of Wing Lee’s laundry at 624 South Fair Oaks. The newspaper lists the name of two Chinese arrested there: Wong June and Wong Sen. On 26 April 1923, Wing Lee’s residence at Pico and Raymond was raided and people there were caught playing dominoes. Wing Lee also alleged that the officers had stolen $9.80 from his home during the raid – which the officers, Arthur A. Fessler and Edwin J. Goins, denied. The police were investigated by the police and found innocent of the crime. Wing Lee also pleaded guilty to possession of an opium pipe and paid a $50 fine. In 1926, Wing Lee again requested police protection from two car-loads of hatchetmen who were said to be coming for him but they never materialized. It was also said that his bodyguard was the father of a policeman. By 1930, one of Wing Lee’s Chinatown community leaders, Frank Wong, claimed that the elderly Wing Lee had by then returned to China to die.

OPIUM DENS

Chinatown opium dens occupied a tremendous amount of real estate in the imagination of non-Chinese but not without reason. There were opium dens, thanks to Britain having grown opium and insisting that it be sold in China. The Chinese attempted to stop the British narcostate from trafficking opium into their country and were met with violence as a result. China fought the first Opium War against Britain in 1839 and 1842. The second Opium War, fought between 1856 and 1960, saw China defeated by Britain and its drug-pushing ally, France. The Chinese introduced opium to California during the Gold Rush. In San Francisco, a law was passed banning opium dens — but not sale, import, or use of opium — in 1875. In 1909, however, importation and use of opium except for medicinal purposes were criminalized.

In 1913, The Times’ Resident Correspondent in Pasadena reported on 23 September that several Chinatown opium dens had been raided by the police.around midnight of the previous day. “Ten pig-tailed gamblers and smokers were herded into the police station.” The names of those arrested at an opium den at Fair Oaks Avenue and Pico Street were recorded as Ah Lu, Ah Lute, Ah Sam, Ah Siam, Ah Sing, and Jung Pah. Ah Jim was picked up at an opium joint on Raymond Avenue and Pico Street. Ah Hi, another Ah Sam, and Ng Lu were picked up for gambling at Raymond and Pico. An opium den at 43 Pico Street was raided, and its proprietor and “ringleader of a gang of ‘dope’ smugglers,” Sling On, was arrested on 29 October 1919.

In 1919, private detective Frank E. Edmondson was arrested by Pasadena’s Chinatown squad for possession of opium. Edmondson had been all set to be appointed the Chief of Police of Venice the very next day when he and other members of an international opium smuggling operation were arrested including police offices Howard J. Proffitt and William E. Hill. They robbed Hom Hing (of 222 Ferguson Alley — in Los Angeles’s Chinatown) of roughly eight kilograms of opium and $4,250 ($76,728 adjusted for inflation to 2024 dollars) during a drug deal in Pasadena’s Chinatown in which they posed as federal officers. Stevedore foreman Athol Matot and a miner, Eugene Strup, were arrested for their part in the smuggling ring in San Francisco.

Finally, on 10 June 1921, Wong Low was arrested by three detectives for smoking opium in his “shack.” They’d been surveilling him for “a long time” and hoped to catch him selling but to no avail. His bail was set at $100. Opium use, obviously, declined over time. The last known opium den in the US closed in New York City in 1957. Gambling, however, is still popular and it was to that vice that Pasadena’s police department next turned its attention.

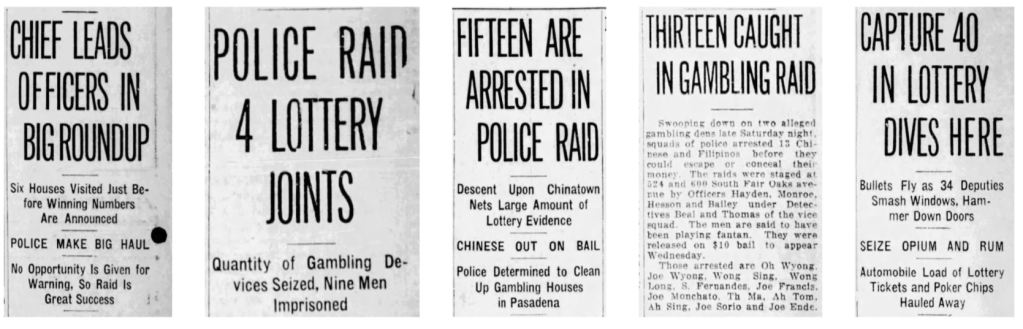

GAMBLING RAIDS

Six supposed gambling houses were simultaneously raided in Pasadena’s Chinatown on 15 December 1922. 33 were arrested for playing the lottery. The Chinese Lottery was invented around 200 BCE. In 1847, the Portuguese government of Macao began granting licenses to lottery operators there. It was brought to California by Chinese rail workers where 白鸽票 was Americanized as “boc hop bu” and “puck-apu.” It was often conducted in laundries, where “pigeon tickets” could easily pass for laundry slips.

One of the first simultaneous raids took place in December of 1922, when houses at 41, 45, and 47 Pico Street were raided. At daybreak on 8 February 1923, three Chinatown gambling houses were raided simultaneously. Charles Chew, Charles Wong, and Jim Hin were each charged with running lotteries. The players arrested, however, were all white this time. Their names were given as C. Bird, C. W. Caldwell, Charles Baum, F. B. Rumsford, H. Abraham, H. Rumsford, H. Taylor, J. Lester, L. Howell, T. Rumsford, and W. Madison — given names nearly always mercifully represented only with initials. There was another raid on 18 February 1925, in which 25 people were arrested — including two black players. The race or ethnicity was almost always deemed relevant in newspaper reports of the day. Two Japanese (C. Kishi and George Kawa) and a Filipino (Angel Cruz) were arrested at 600 South Fair Oaks for playing fan-tan (番攤) 16 May 1925.

The biggest raid took place on 28 October 1925 and sounds like a bit of a circus… or, less charitably, a clown show. Ensenada’s Chief of Police, Ernesto Silvas, was on hand to witness “how American peace officers did their stunts” with his daughter, Clementine, who watched from the sidelines. 34 deputy sheriffs battered down dogs in search of gambling and opium. It was initially reported that “deputies were greeted with bursts of gunfire when they smashed the doors of two houses” but the story was later changed. Apparently some boys lit firecrackers that the police mistook for gunfire and the only guns fired that day were by the police. According to a newspaper account, “a fusillade of revolver fire” had been “necessary to halt a number of fleeing orientals.” 70 were arrested and 40 were immediately released. The Pasadena Post reported that the raid netted a seizure of opium and rum although it was later downgraded to a single opium pill in the pocket of one Wong Tong. It seems that it maybe been some other type of pill as was later reported that “They failed to find any trace of narcotics.” There was violence, however, as two police “officers suffered lacerated hands from broken glass” that they’d presumably smashed during their performance. The purpose of the raid, it seems, was to have been capture the infamous Wing Lee. The tong leader paid $750 bail for himeself and $500 each on his assistants – Jim Yeung Hay and Jue Sing.

FRANK WONG (AKA BIN QUONG WONG)

A raid on 13 January 1927 of Sam’s Laundry netted Wong Kee, Wong Fong, and Frank Wong. Frank Wong was again arrested during a raid on 30 November 1927 at his own residence. Wong and three others were arrested at his residence for gambling on 4 April 1928 and again, on 14 July 1929. Despite his record, Wong soon came to be recognized as a Chinatown community leader. When violence between Tongs in New York City resulted in the deaths of five people, the Pasadena police began surveying the community warily, which was already by then in decline. A writer at The Pasadena Post described Chinatown as “a little settlement surrounded by Mexican dwellings.” Unable to help himself from indulging in a bit of dog whistling, he continued “The row of tiny houses where bland faced orientals sit on doorsteps evenings puffing blueish smoke from queer long stemmed pipes, has diminished during the past decade, but, according to police, still is a potential tong war hotbed.” Apparently incapable of entirely ignoring reality, the newspaper man sounded a less sensational note. “Most of the inhabitants of the one street left of the once thriving ‘village’ which extended almost to Colorado street, are engaged in laundering or driving vegetable wagons.”

It was presumably a different writer at the Post who interviewed Frank Wong in August, and described him as a “World war hero, Los Angeles business man and thoroughly Americanized leader of the little Chinese settlement here.” Wong claimed that the there were no longer Tongs active in Pasadena. “They have all gone–some back to China and some to other cities.” He went on, however, to expound upon the role of the Tong in the community, stating “To Chinese in the country, unable to speak English and ignorant of American customs and laws, the Tong is his salvation.The Tong leads him to live a right life, finds him a job, patronizes his concern and settles his business litigation.” Wong also concluded that there was “no need of police protection for Pasadena Chinese.” “Chinatown is peaceful now,” Wong concluded.

THE MURDER OF JOE WONG (AKA BIN G. WONG)

Frank Wong’s brother, Joe Wong (aka Bin G.Wong or Bin T. Wong), lived at the “family residence” at 35 Pico Street. In the 1910s, it had been the home of Sing Pag Chew. When he learned of an illness, however, he’d shot himself in the head and died there in 1920. It was one of the houses raided for gambling in 1925. In 1929, Joe built a small, brick store across the street, at 36 Pico, for $3,500. It was referred to in at least one instance as a “novelty shop.”

In 1930, two black men entered into the store owned by Frank’s brother, Joe Wong, and attempted hold-up on. According to The Pasadena Post, they first attempted to pass themselves off as officers who were raiding them for gambling. Also there were Frank Wong, Albert Wong, Wong Jung, Wong Hung, and Wong Yot. As he attempted to escape out the back door, Joe Wong was shot and killed by Theodore Albritton. Albritton and his accomplice, Ben Smith, were both soon picked up, tried, and sent to jail. Also arrested for his involvement was Frank M. Shiraishi, who’d aroused the suspicion of the men at the store for pacing up and down the street outside of it, in the rain, in the moments leading up to the shooting.

In March, as he awaited trial, Shiraishi almost escaped from his solitary confinement cell by climbing the bars and kicking a hole in the ceiling of his cell. It later emerged that Shiraishi had called Joe Wong in advance of the attempted robbery in order to warn him. He had hoped that Wong, prepared for the robber, would’ve shot and killed him instead of the other way around. It turned out that Shiraishi was in love with Albritton’s girlfriend — a 23-year-old white woman who gave her name as Billie Russell. She also went by Ethel Fontaine. Her birth name was Ellen Caraway. It also transpired that she and Albritton had earlier robbed a “chop suey parlor” in Florence of $303. During the trial, two of the jurors — Charles Wills and Frank J. Coyle — asked Wong to pay them in return for a favorable verdict. He reported them, instead, and they were replaced. The trials of the three men ended with their being sentenced to life in prison and sent to San Quentin.

It wasn’t Wong’s last brush with the law, however. He was again fined for conducting a lottery in July 1931. In September 1940, he went to China on vacation. Two months later, it was reported, that he’d gone missing. His fate, as far as I know, remains a mystery.

HAY CHEW

With Wing Lee and Frank Wong gone, Hay Chew emerged as the last of Chinatown’s lottery operators. A raid at 627 South Raymond resulted in the arrest of Wong Kee and Wong Sue on 22 June 1936. Hay Chew, however, was arrested for operating a lottery at 45 Pico street in 1936 and again in 1937. At the 1936 arrest, the reporter for The Pasadena Post noted that “Time was when such institutions were common in Pasadena but they have been whittled down until Mr. Chew, apparently, is the only one who chooses to run one. The final bust I could find was from 22 January 1937. On that occasion, The Pasadena Post’s reporter noted:

When it was all over the two officers had philosophic Chew Hay, who has been arrested so many times on the same charge it is an old story, and three customers in their clutches. At the police station the bland Oriental, as he always does, drea out a roll of green bills and paid $50 for himself and $10 each for the captured three who gave their names as James Huey, 30; Howard Wong, 30; and Charley Lee, 40.

CHINATOWN CODA

The area containing Chinatown and Sonoratown were changing. Many of the Chinese men who’d lived there had moved back to China, moved on in search of more lucrative prospects, or merely “moved on.” After 1968, there would be another wave of Chinese-speaking immigrants although this time around they’d be mostly from Hong Kong and Taiwan‘s middle classes.

The Mexican school, Junipero Serra, was closed in 1931. People began referring to the neighborhood as Arroyo Del Mar — derived from Del Mar Boulevard and the Arroyo Seco Parkway, which Broadway became part of at some point after the parkway opened in 1940. By then, there are no mentions of Chinese on Pico — and with no Spanish speakers to correct them, no one seemed to know (or care) that “Arroyo Del Mar” translates, nonsensibsly, to “Sea Creek.”

Frank Wong’s home, seems to still stand. According to the County Assessor, it was substantially altered in 1930 and is today home to Fair Oaks Law. The only other building from the era that still stands today is his brother Joe’s shop, where he was murdered. Its windows are boarded up and they — and the store’s yellow bricks — are now painted white. Otherwise, Pico Street is nondescript — lined by surface parking lots and the backs of buildings. One notable exception is the street lights, with their acorn-shaped glass, which I would guess also date from the era. Maybe someone else can shed some light on that theory.

FURTHER READING

“Pasadena’s Forgotten Neighborhoods: Residential and Cultural Aspects of Pasadena’s Commercial Sector in the Early twentieth Century” by Marguerite Duncan-Abrams (1990)

“Ethnic History Research Project Pasadena — Report of Survey Findings” (1995)

CAST OF CHARACTERS

I’m including this cast of characters, mostly taken from arrest reports, not to reflect poorly on the Chinese community — but with the hope that they can aid the curious in their research of Pasadena’s Lost Chinatown. At, currently, 42 — it represents a fairly large proportion of the community. The 1910 census, for example, counted 102 Chinese living anywhere in the city.

- Albert Wong — Witness at the murder of Joe Wong.

- Bong Fu Ching — Managed the fruit packing facility at Ritzman (now Filmore) and South Raymond in 1910.

- Charles Chew — Charged with running a lottery at 47 Pico Street in 1923. He was found not guilty.

- Charles Wong — Charged with running a lottery at 45 Pico Street in 1923.

- Ching Wing — A laundry worker who was naturalized in 1900 and who lived at 38 Pico Street.

- Frank Wong (Wong Bing Quong) — Brother of Joe Wong. First World War veteran in California’s 26th Division. Member of the Pasadena American Legion. Lived at 488/490 South Fair Oaks. In September 1940, he went to China on vacation and vanished.

- Gee Town — a grocery worker who lived at 624 S. Raymond in 1920.

- Hay Chew (Chew Hay) – Arrested in 1936 and ‘37 for running a lottery at 45 Pico Street. Said to be the last lottery operation in Pasadena.

- Herbert Wong — Witness who testified in the Joe Wong murder trial. Lived at 34 Pico Street and worked as a busboy at the YMCA. Reported the theft of a fountain pen, gold watch and $7 in 1925.

- Hong K. Low — a gardener, naturalized in 1870, who lived at 624 S. Raymond.

- Jim Hin — Arrested for conducting a lottery in 1923 at 41 Pico Street.

- Joe Kay — Arrested in 1922 for lottery at 47 Pico Street

- Joe Wong (Bin G. Wong) — The brother of Frank Wong. Arrested in 1922 for playing the lottery at 41 Pico Street. Perhaps the same Joe Wyong arrested at fan-tan parlor in 1925. Lived at 35 Pico Street. Built the only remaining shop from the Chinatown era, at 34 Pico Street, in 1929. He was shot and killed there in 1930 in an attempted hold-up.

- Jue Jun — Arrested in 1922 for playing the lottery at 47 Pico Street.

- Lem Sing — Arrested in 1922 for playing the lottery at 39 Pico Street.

- Leow Sing — “Unsavory” character accused of stealing chickens in 1892.

- Lim Foon — A young man who lived on Pico and who worked as a cook nearby in Bellfontaine. On the eve of returning to China, he supposedly murdered the chauffeur of his employer before he was jealous, and then commit suicide.

- Lin Kee — Ccourt interpreter who followed Yuen Kee to Mills Street. Later the first Chinese married in Pasadena.

- M. I. Young — Arrested for latter in 1925.

- Oh Wyong — Arrested at fan-tan parlor in 1925.

- Po Ho — Found guilty of operating a lottery at Frank Wong’s in 1927.

- Sing Pag Chew — Committed suicide on 10 March 1920 at 35 Pico Street with a revolver.

- Sling On — Operated an opium den at 43 Pico Street that was raided in October 1919.

- Th Ma — Arrested at fan-tan parlor in 1925.

- Tony Wang — Arrested for lottery in October 1925.

- Wing Lee — “Last of the Pasadena tong men” turned elderly laundryman, Member of the Bing Kong Tong. Moved back to China “to die” before 1929.

- Wong Jung — Witness at the murder of Joe Wong.

- Wong Hung — Witness at the murder of Joe Wong.

- Wong Kee — Arrested in 1922 for lottery at 41 Pico Street. Arrested again on 3 March 1925 for operating a lottery at his him. Lived at 450 [?] Pico Street. Re-caned chairs at 41 Pico Street. Arrested again on 22 June 1936 for operating a gambling place at 627 South Raymond.

- Wong Koon — A chair repairer who lived at 625 S. Raymond in 1920.

- Wong Long — Arrested at fan-tan parlor in 1925.

- Wong Low — Arrested in 1902 for smoking opium and suspected of dealing. Failed to show up for trail after posting $100 bail.

- Wơng Quang — Arrested for conducting lottery in 1922 at 45 Pico Street.

- Wơng Que — Arrested for conducting lottery in 1922 at 45 Pico Street.

- Wong Sing — Arrested for lottery operation on 18 February 1925 and at a fan-tan parlor in May 1925.

- Wong Sue — Arrested for gambling at 627 South Raymond on 22 June 1936.

- Wong Tong — Arrested for conducting lottery in 1922 at 43 Pico Street. In the big raid of October 1925, he supposedly had an opium pill on him. It’s not clear whether or not it’s the same Wong Tong, but in 1933, a prisoner escaped when a jailer was called to release Sento Tiara [Taira?] and one Wong Jung Tong identified himself as Sento and was released. It was apparently not an uncommon name. In 1937, a laundry worker named Wong Shew Tong was arrested for striking Pasadena cyclist Glen Boight with his car in a hit and run.

- Wong Yot — Witness at the murder of Joe Wong.

- Ye Hing — “leader among the local Chinamen” (Los Angeles Herald, 1905)

- You Wong — a laundry worker, naturalized in 1875, who lived at 624 S. Raymond in 1924.

- Yuen Kee — A laundry man who was the first Chinese businessman in Pasadena and whose laundry was burned down by a right wing mob in 1885.

- Yuen Wah — Lived at 488 South Raymond Avenue. In November of 1920, two “lads,” Azzie Sheard and Oscar Turner, threw rocks at his residence. The Pasadena Post reported, “Time was when it was ‘open season’ on Chinamen in California, but that time is gone and each of the lads had to pay a fine of $1 for their fun. The Chinaman is an old resident of Pasadena with a perfect record for peace and quiet. Yuen was arrested in 1922 for operating a lottery at “northeast corner of South Fair Oaks and Pico.”

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hey Freelancer!, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, the Los Angeles County Store, Sidewalking: Coming to Terms With Los Angeles, Skid Row Housing Trust, the 1650 Gallery, and Abundant Housing LA.

Brightwell has been featured as subject and/or guest in The Los Angeles Times, VICE, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, Office Hours Live, L.A. Untangled, Spectrum News, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, Notebook on Cities and Culture, the Silver Lake History Collective, KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, All Valley Everything, Hear in LA, KPCC‘s How to LA, at Emerson College, and at the University of Southern California.

Brightwell is currently writing a book about Los Angeles.

You can follow him on Ameba, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, iNaturalist, Instagram, Letterboxd, Mastodon, Medium, Mubi, the StoryGraph, Threads, TikTok, and Twitter.