If you’re American and you recognize names like “Bad Boys Blue,” “C.C. Catch,” “Sandra,” or “Modern Talking,” there’s a good chance that you, or someone close to you, is Vietnamese. For the uninitiated non-Viet Americans, those are the names of three German (and one German-Dutch) pop bands whose songs have been compiled, covered, and claimed by a subset of the Vietnamese American community as “New Wave.”

There are other groups in the New Wave canon like Gazebo, Ken Lazslo, Fancy, Joy, and Silent Circle whose hits are familiar to thousands of Vietnamese Americans. Meanwhile, having worked in record stores for more than ten years, I can say that none of my coworkers, no matter how knowledgeable, had ever heard of any of them.

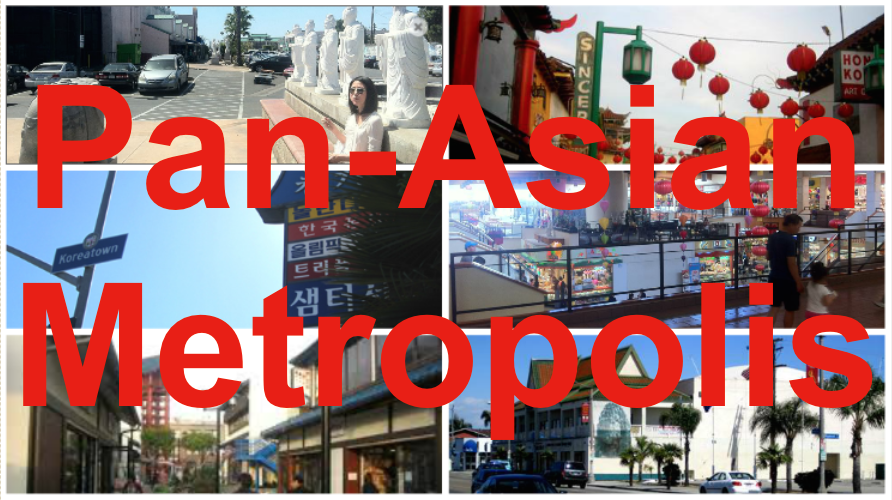

How, I wondered, did these Eurodisco acts become so cherished by such a specific segment of a specific population of refugees and their descendants — especially when there’s no obvious connection between West Germany‘s pop industry and Vietnamese refugees in the US. I never solved that riddle, but my curiosity and love of those songs led me on numerous occasions to parties and nightclubs in North Orange County‘s Little Saigon.

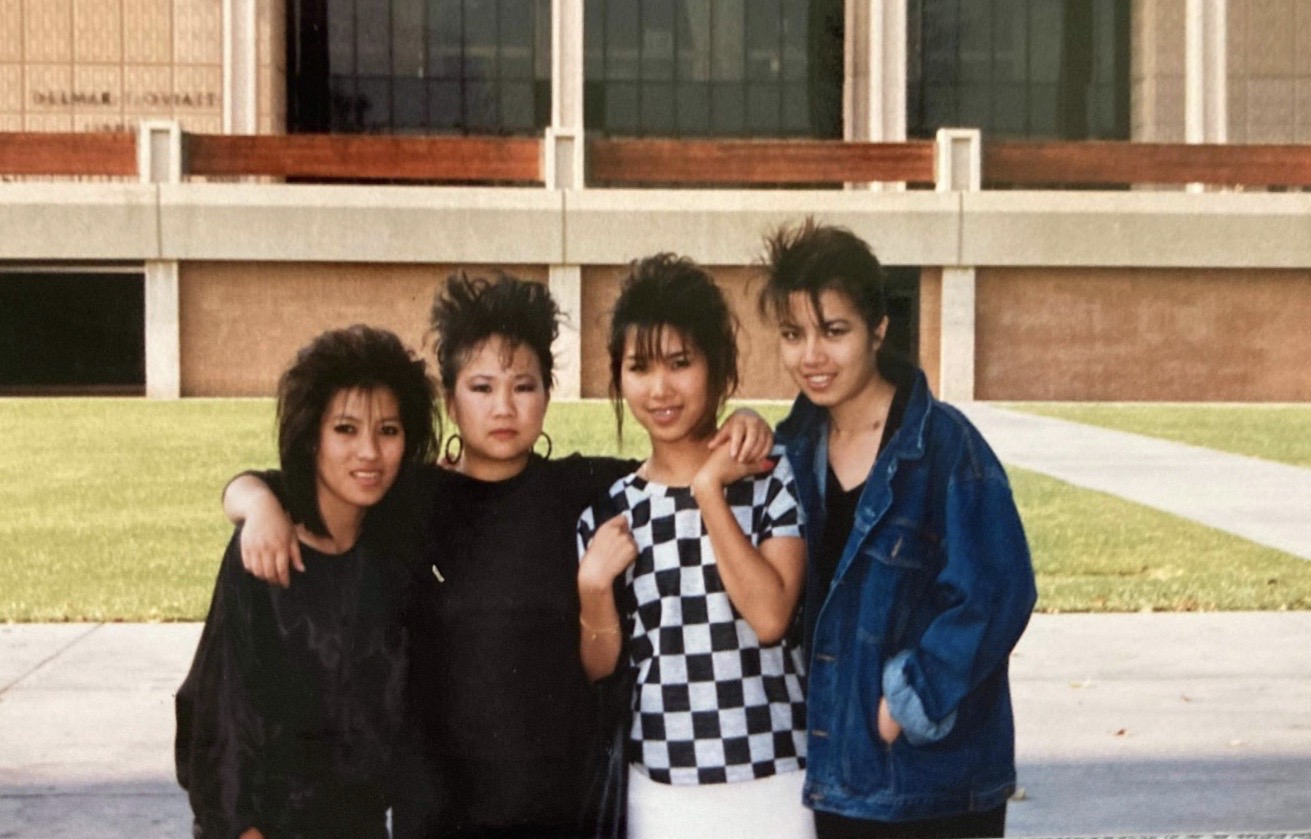

Last year, a filmmaker named Elizabeth Ai contacted me. She is currently in the process of making a documentary and television series, both called NEW WAVE. More recently, she started companion Instagram and Facebook accounts to which people can submit photos of themselves from that era, hair immaculately fixed with hairspray, and often clothed in black.

ERIC BRIGHTWELL: Hello Elizabeth, can you tell us a bit about yourself — who you are, where you’re from, and what you do?

ELIZABETH AI: The short answer: I’m a Chinese-Vietnamese-American filmmaker from the San Gabriel Valley.

The long one: It’s hard to talk about who I am without talking about my family and the multi-generational fleeing they’ve done from war-torn countries — a family tradition I might continue depending on what happens this November. My maternal great-grandparents fled China to Vietnam in the 1920s because of the Chinese Civil War. And my grandfather, an ARVN captain, upon release from re-education camp, fled Vietnam with his wife (my grandmother) on a fishing boat to Hong Kong in the late ’70s. Fortunately, they had family members already situated in the US that helped them figure out sponsorship through their church. My aunt and uncles arrived right in time for the golden age of MTV. I was the first US-born person in my family, raised by my grandparents, and have struggled all my life with these multiple historical narratives that make up my DNA.

The long one: It’s hard to talk about who I am without talking about my family and the multi-generational fleeing they’ve done from war-torn countries — a family tradition I might continue depending on what happens this November. My maternal great-grandparents fled China to Vietnam in the 1920s because of the Chinese Civil War. And my grandfather, an ARVN captain, upon release from re-education camp, fled Vietnam with his wife (my grandmother) on a fishing boat to Hong Kong in the late ’70s. Fortunately, they had family members already situated in the US that helped them figure out sponsorship through their church. My aunt and uncles arrived right in time for the golden age of MTV. I was the first US-born person in my family, raised by my grandparents, and have struggled all my life with these multiple historical narratives that make up my DNA.

Are you asking me where I’m from or where I’m really from? JK. — I grew up in the SGV  (San Gabriel Valley) in the shadow of the L.A. riots. Where I grew up, at the time, looks vastly different than the safe neighborhood it is today. Somehow I managed a 4.0 GPA when I used to sneak out with friends to cruise Valley Boulevard on school nights in lowered cars, with modified exhausts, to hang in Hong Kong-style cafes or party with fake IDs in Koreatown nightclubs. Back then, in the SGV, there was a lot of gang activity, even drive-by shootings at my school, and I was a young latchkey kid that was stupid enough to not

(San Gabriel Valley) in the shadow of the L.A. riots. Where I grew up, at the time, looks vastly different than the safe neighborhood it is today. Somehow I managed a 4.0 GPA when I used to sneak out with friends to cruise Valley Boulevard on school nights in lowered cars, with modified exhausts, to hang in Hong Kong-style cafes or party with fake IDs in Koreatown nightclubs. Back then, in the SGV, there was a lot of gang activity, even drive-by shootings at my school, and I was a young latchkey kid that was stupid enough to not  care. My experiences from hanging out in these streets were just as informative to who I am as my time in the classroom, if not more.

care. My experiences from hanging out in these streets were just as informative to who I am as my time in the classroom, if not more.

Professionally, I’m a writer, producer, and director working in documentaries and narratives for almost fifteen years. I’ve focused on stories that illuminate subjects and issues from marginalized and underrepresented communities. It’s been a long circuitous path fighting upstream against a white, male-dominated, entertainment industry that still diminishes the value and work of women, BIPOC, and LGBTQIA+. I don’t take what I do for granted. Never would my teenage self dare dream that my adult self would be working in such a privileged profession and be in a position to tell stories.

When did you become aware of “new wave?”

New wave has been in my life for as long as I can remember. It was the soundtrack to my childhood. While this music was really my aunt’s and uncles’, who were in their late teens and twenties, growing up with them meant it was ever-present in our home, and my grandparents hated everything it represented in this era of excess. On the flip side, I fondly remember tracks by Modern Talking, C.C. Catch, and Bad Boys Blue playing from the boomboxes in their bedrooms while they meticulously teased their mile-high Aqua Net-styled hair and slipped into their beat-up leather jackets, and thinking, I could not grow up fast enough to join them. For better or worse, that didn’t happen. I came of age in a different era, listening to gangsta rap, ’90s R&B, and the oldies that Art Laboe was spinning, but that new wave sound has always held a special place in my heart.

Modern Talking’s music video for “You’re My Heart, You’re My Soul”

What made you decide that “new wave” would be an interesting subject for a documentary?

Let’s get one thing straight, this music is fucking amazing! I didn’t realize how many bangers there were until I fell down the rabbit hole of research and started making playlists. Everyone who is not listening to it is missing out.

While I was pregnant a couple of years ago, I was racking my brain for stories to share with my daughter about our people and why we’re here in the US, then felt pretty deflated thinking I might have to resort to rote stories about the war. That was until my mind wandered into events I experienced first hand like my family’s early days rebuilding their lives in the ’80s. Like most children of refugees, I didn’t have an ideal childhood. The trauma in my household was real and the generational gap between my disciplinarian POW grandfather and his children, all of whom were struggling to find their identity in a new country, led to many explosive clashes. The lows were really low, and the highs weren’t that high. And when I look back, what really stuck with me was witnessing my young adult uncles and aunt living their best new waver lives. I often kept their secrets and told lies of their whereabouts to my grandparents (their parents) in exchange for passage on weekend car rides, where they’d blast new wave all the way to the mall and hang with their friends. It sounds silly to say but, new wave was a necessary diversion, a coping mechanism that brought them joy. Wherever new wave was playing was a safe space. They knew they could congregate with other young Vietnamese, and momentarily escape pressures from home, their past trauma, and just be whatever version of themselves they wanted to be.

Lynda Trang Đài’s cover of “You’re My Heart, Your My Soul”

Reviving these long-buried memories inspired me. Knowing there are so few stories about the Vietnamese diaspora experience that aren’t tied to images of war and destruction, Vietnamese new wave felt like a great personal point of departure. So much that after giving birth in 2018, I wrote a rough draft of a TV pilot based on these recollections. Reading it over, I realized, something was missing. I was pulling from cobwebbed memories that didn’t have the specificity I craved. That’s when I began scouring the internet about the evolution of the Vietnamese-American community in Little Saigon, the beginnings of its music industry, and eventually came across your Vietnamese New Wave Revival blog post and discovered that the music was actually Euro/Italodisco. Wait, what? Why did everyone in the Viet-Am and diaspora community call this music new wave? These artists were from Germany, France, Italy, and everywhere else but the US? I had so many questions. I scrambled to call up family members that sent me off to call up other relatives that told me to call their friends that knew more about new wave. I was shocked when a couple of them confirmed that none of this music had played on the radio. They told me they bought all these European records and Viet New Wave covers/cassette compilations at record shops in Phước Lộc Thọ (aka Asian Garden Mall) because there was nowhere else to buy them at the time. It was a big “what the fuck?” moment that flooded my head with even more questions.

Was the music of my childhood really some imported Eurodisco fever dream? There was enough of a mystery there that I pivoted the story of my TV pilot and then enlisted some friends to help me jump start the documentary, namely, my co-producers Tracy Chitupatham and Anh Phan, as well as some advisors to make introductions and discuss that specific era. I’ve been filming since early 2019 with over a dozen people from the Vietnamese-American music community, including Lynda Trang Dai, Thai Tai, Ian DJ BPM Nguyen, some die-hard new wave fans/party promoters, and I even flew out to Europe at the end of last year to film with some of the big-name Eurodisco acts of the ’80s.

There’s a lot to unpack about the resettlement and reestablishing of a people and culture. I’ve narrowed my focus to examine the evolution of refugee youth identity and the cultural bridge built during this fraught time with this music. Moreover, I’m telling this story for a few reasons: one, as a time capsule for my daughter and younger generations to learn a story about our resilient community beyond the war; two, to keep a historical record that will otherwise be lost when the artists and fans disappear; three, because this work is therapeutic, cathartic, and honestly, I’ve just fallen in love with it all over again. The more I listen to it, the more I wonder why new wave and I have been estranged for so long.

What was the incentive behind the Instagram feed, @newwavedocumentary?

Production for our film halted in March because of Covid-19. Coincidentally, this was the same time we learned of NEW WAVE’s first grant award from California Humanities. In making the most of it, I pivoted and immersed myself in archival research and I quickly realized the limitations and lack of Vietnamese-American archives, that aren’t of the musicians and don’t involve the war in some capacity.

My team and I started the Instagram account in hopes that it’ll motivate others to share photos or videos from their personal archives.

What has the response been?

It’s been positive. I’ve had friends and strangers inquire about the film and how they could support. Some rad photos and stories have come through. Thanks to everyone who has shared. My team and I are still digging through everything and hope to post all your stories and photos soon enough.

How can people get involved? (social media, etc)

We want to hear from you. Please get in touch and share your stories with us on Instagram and Facebook or via researchnewwave@gmail.com. We’re searching for photos and videos after the fall of Saigon from the ’70s-’90s focused on the era of resettlement, rebuilding, and all things new wave, or tangentially new wave.

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, Los Angeles County Store, the book Sidewalking, Skid Row Housing Trust, and 1650 Gallery. Brightwell has been featured as subject in The Los Angeles Times, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, and on Notebook on Cities and Culture. He has been a guest speaker on KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, at Emerson College, and the University of Southern California.

Brightwell is currently writing a book about Los Angeles and you can follow him on Ameba, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Mubi, and Twitter.

Thanks for the article and turning me onto this documentary. I asked some of my older siblings about where the New Wave trend came from and my oldest brother said the music was popular in Vietnam during the early eighties as well so, considering back then Viet Americans weren’t traveling back there, it was likely brought over from Viets coming here. Here’s an article about how popular the German band Boney M was in Vietnam in the early 80s (and now): https://saigoneer.com/saigon-music-art/12960-for-the-love-of-boney-m-how-a-west-german-disco-quartet-charmed-vietnam.

LikeLike

A little history…maybe this would help with the documentary.

Actually the ‘Asian New Wave’ trend was made popular by DJs here in southern CA, particularly from record stores in the Los Angeles area. One of which I remembered vividly from my earliest days (c. ’84-’85) was DMC Records owned by ‘DJ Larry’ whom would throw weekly parties at rented local college halls and Masonic Temples, drawing huge crowds from all over southern CA. I don’t know Larry that well on a personal level but I’ve visited his original shop regularly when it was on Melrose/adjacent Vermont Ave (the old location before he moved further west to the Melrose Strip and now defunct). He’d always hook me up with a few blank cassettes whenever I purchase the new releases. Another store was Funkytown Records located on Western in Koreatown, here I actually knew the guys pretty well, mind you I’ve hung out there on almost every weekends! This was the record store that helped promoted Shere Thu Thuy of “Gonna Lose My Heart” fame which I saw her regular visits. Subsequently I’ve also befriended individuals from Street Sounds and Prime Cuts in the West Hollywood area as my journey continues – searching for that lost genre of the golden days my youth, where the buys worked there refer to them as ‘Asian new Wave’ with the likes of “Modern Talking, Fancy and Gazebo” and I agreed! This was circa ’91-’94. I even went as far as having my ‘out-of-prints’ coming from a few sources out of Frankfurt, Germany via GEMM, a once beloved portal where diehard vinyl fans shop, until now Discogs!

Speaking of Boney M., he wasn’t an ‘Italo’ nor ‘New Wave’ artist until later when the Eye Dance record album was released in ’85 produced by Frank Farian. The most popular tune on the record was ‘Young Free & Single’ where Boney M. was ‘featured’ and put on the map which has a Eurodance or ‘New Wave’ feel to it. The track was actually sung by Reggie Tsiboe. It is very obvious from his vocals differentiating from Bobby Farrell – aka Boney M.

During the late 70s and 80s Bernhard Mikulski, a W. German distributor behind the popular label ZYX Records had distributions all over the world. They were able to help pushed the genre of both Italo Disco and Eurodance further covering most eastern parts of Europe, Asia, and the Middle-East. This also helped popularized artists such as Fancy, Sandra, and of course Modern Talking. This ultimately gave birth to many obscure and one-hit-wonders released under the ZYX label from 1983-1987, to an extent 1988, where the decline of Italo Disco begins…or should I say…’New Wave’

LikeLiked by 1 person