Los Angeles was at one time home to the largest population of Japanese outside of Japan and the contributions of Japanese-Angelenos to history and culture are many. It was in Los Angeles that Hollywood created the first Asian-American film star. It was also in Los Angeles that a legal challenge in the Supreme Court re-shaped immigration in the US. Los Angeles also played a key role in disseminating Japanese pop culture around the world.

The impetus for writing this came from another project for which I was contracted to work. In the course of my research, I compiled far more information than that job required (or allowed). And so, I thought I’d try to organize the information into this overview of Japanese Los Angeles. Although I’ve made considerable effort to create a fairly exhaustive timeline, I’m as always, open to suggestions, corrections, and additions. Just leave them for me in the comments. Thank you!

The first major interaction between Japan and the US occurred in 1853 when American Commodore Matthew C. Perry arrived in Japan with a fleet of warships and demands that Japan open its ports for trade. In 1868, Emperor Meiji emerged victorious over the Tokugawa Shōgunate, ushering in an era of reform known as the Meiji Restoration. Modernization involved (among other things) eating livestock animals (previously taboo) and expanding the country (which Japan did when it conquered the Ainu homeland to the north in 1869 and renamed it Hokkaido).

Under the new emperor, the Japanese also gained the right to leave the country and many did so in search of employment. It was in 1869 that the first presence of Japanese in Los Angeles County was recorded. Two teenage house servants, listed as Ta Komo (18) and E. Noska (13), were employed at Judge Edward J.C. Kewin‘s residence, El Molino Viejo, in San Marino.

Following the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, railroad tycoons began courting Japanese workers to take their place in Southern California. In 1884, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway hired 24 Japanese men for work in Los Angeles.

In 1886, an ex-seaman known as Charles Kame (and likely born Shigeta Hamonosuke) opened a diner at 340 East 1st Street — the first Japanese-owned business in Los Angeles. Two years later, Kame sold the restaurant. By 1890 he had left Los Angeles altogether. The next two Japanese to establish businesses were likely Akita Sanshichi (c. 1857-1920) and George Izawa.

Following the example of the European empires and the US, Japan’s program of modernization involved expansionism. The First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) saw Japan and China warring for influence over Korea. In 1895, Japan also defeated the Republic of Formosa, inaugurating five decades of Japanese rule in Taiwan and establishing Japan’s first overseas territory since they conquered Ryūkyū in 1879.

By 1888, there were approximately 70 Japanese living in Los Angeles, most of whom were employed in restaurants — and mostly in restaurants that catered to Americans by serving staples like beef stew, chicken dinners, turkey dinners, stewed fruit, pie, pudding, and ice cream. The number of Japanese-owned businesses grew to sixteen in 1896. In addition to restaurants, Japanese-Angelenos also owned barbershops and bamboo furniture stores. Japanese merchants of the era included Inosuke Inose (1856‐1939, proprietor of Sunrise Restaurant, 209 East 1st Street), Benjamin Bungoro Mori (1869‐1964), Hideo Muta (1870-1951, proprietor of The Mikado), and Harry T. Tomio (1881-1971).

Japanese began enrolling in California colleges and universities in large numbers and from 1902-1907, the number of Japanese students enrolled in California schools rose from roughly 1,200 to 2,972. Meanwhile, the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), in which the Empire of Japan defeated the Russian Empire for control of Korea and Manchuria. As a result of Japanese warmongering and the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, hostility against Japanese and Japanese-Americans began to grow. The US and Japan made an informal Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907, which stated that the US would no pass anti-Japanese legislation so long as Japan stopped issuing passports to Japanese men. As a result, about 10,000 Japanese men emigrated to the US in the run-up to the implementation of the agreement. Afterward, only Japanese women and children came to the US, ushering in the era of the picture bride.

By the dawn of the 20th century, there were about 200 Japanese living in Los Angeles. A second Downtown Japanese enclave arose along West 6th Street. A third, mostly residential Nihonmachi arose along Fedora Avenue, which came to be known as Uemachi or Uwamachi. Most residents of the latter were gardeners although, in 1903, Pacific Electric Railway-owner Henry E. Huntington hired Japanese to replace recently unionized Mexican workers. In 1905, a group of Ryūkyūans who’d previously worked in Mexican gold mines made their way to Los Angeles. By that time, the number of Japanese women living in Los Angeles was still in the double digits.

In the wake of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, between two and three thousand Japanese relocated from the San Francisco Bay area to Los Angeles. By then, the Japanese enclave along 1st Street was home to bathhouses, bookstores, nomiya, pool halls, and

restaurants, all catering to Japanese clients. As early as 1906, the enclave had acquired the colloquial nickname of “小東京” or “Little Tokio.” A year later, a San Francisco transplant Gentaro Isoygaya opened the city’s first sushi restaurant at 116 Weller Street.

Many Japanese-Angelenos also rented land on which to grow fruits and flowers. The first Japanese to lease a ranch did so in 1901. In 1904, there were 24 Japanese farmers growing strawberries — a fruit with which they came to be closely associated. Japanese gardens were also popular amongst Los Angele’s social elite and in 1904, Henry E. Huntington had an entire home shipped from Japan to be placed in the Japanese garden at his San Marino estate — now part of the Huntington Botanical Gardens.

In 1906, a group of Japanese gardeners organized the California Flower Growers Association. A frost in 1907, however, compelled many Japanese farmers in Harbor City, Los Feliz, San Fernando, Venice, West Adams, and Wilmington to switch from fruits and flowers to heartier vegetables. Meanwhile, the Japanese continued to farm flowers in Pacoima and Sun Valley. By 1909, two-thirds of Japanese-Angelenos worked on farms.

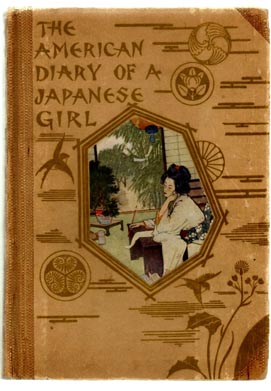

There were other significant developments within the Japanese-Angeleno community in the 1990s. In 1903, Masaharu Yamaguchi, Rippo Iijima, and Seijiro Shibuya launched the community’s first Japanese newspaper, Rafu Shimpo (羅府新報). In 1904, future-famed sculptor Isamu Noguchi was born to poet Yone Noguchi (author of the first novel published in the US by a Japanese-American writer) and writer Léonie Gilmour. In 1909, acclaimed photographer Tōyō Miyatake (1895-1979) moved to a house on Jackson Street. His photography studio was at 364 East 1st Street.

Japanese rule of Korea began with the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876 and continued with the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 (which made the Korean Empire a protectorate of Japan). It was with the passage of the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910, however, that the Korean Empire was annexed by the Empire of Japan. In 1912, Emperor Meiji died and was succeeded by Emperor Taishō. Two years later, Japan aligned itself with the Allied Powers in World War I and declared war on Germany — making it the only one of the principal allies in Asia. In 1915, Japan issued its Twenty-One Demands to China and Japan’s fellow Allies (too busy already enjoying similar imperial spoils) did nothing to object.

By 1910, Los Angeles County was home to 8,461 Japanese. Los Angeles was thus home to a larger population of Japanese than any other American city — even if they did comprise less than 2% of the populace. Most, too, were ineligible for citizenship, thanks to the Alien Land Law of 1913, which even barred Japanese from holding long-term leases. Without such leases, more Japanese turned from agriculture to horticulture and floriculture which require less land.

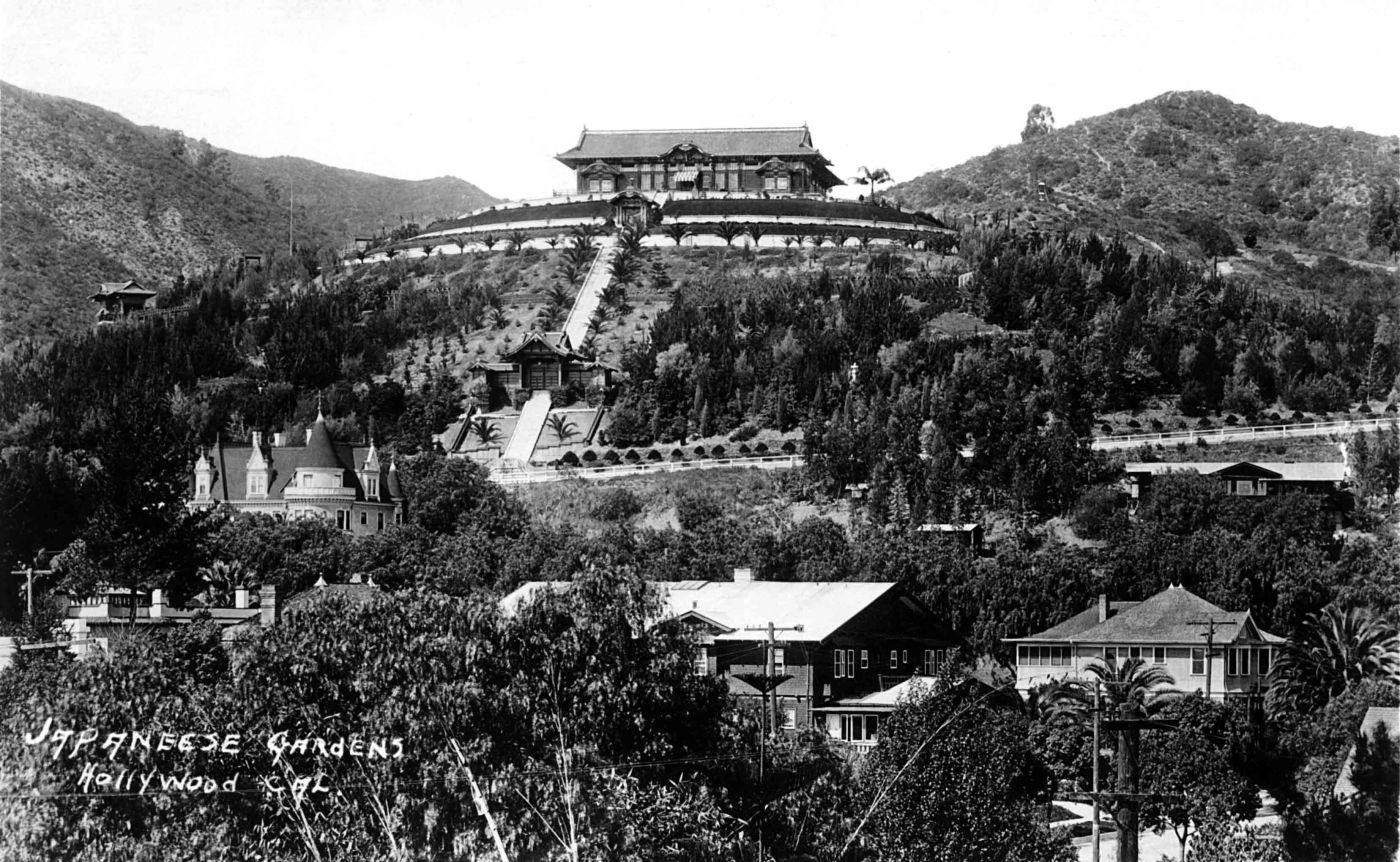

By 1912, there were already 54 Japanese florists and the continued popularity of

Japanese landscape design was evidenced by the construction of Adolph and Eugene Bernheimer’s Japanese-inspired Yamashiro estate. In 1913, the Flower Market opened as the Japanese Market. Japanese continued to farm, too, however, and by 1915, about three-quarters of all vegetables consumed by Angelenos were grown by Japanese farmers.

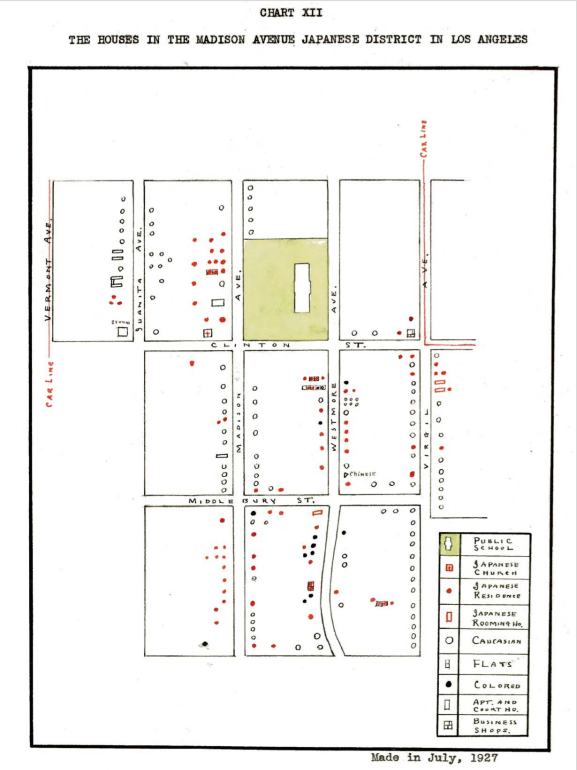

With only women and children allowed to immigrate from Japan (mostly through the port of San Francisco), Japanese Angelenos continued to spread from cramped, urban Little Tokyo into new suburban enclaves like Furusato (on Terminal Island) and Madison/J. Flats (in East Hollywood). Uwamachi, meanwhile, expanded into Pico

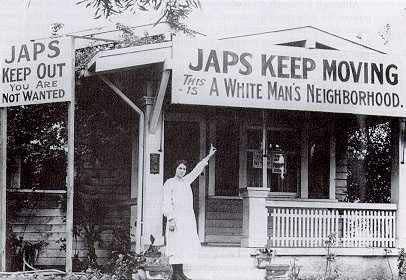

Heights. As the Japanese moved into new overwhelmingly white neighborhoods, anti-Japanese sentiment grew more pronounced and, in turn, more anti-Japanese citizenship laws were passed and residential restrictions increased. In Pico Heights, members of the Los Angeles County Anti-Asiatic Society formed the Electric Home Protective Association.

The community of Hollywood only became part of Los Angeles in 1910, the same year D.W. Griffith filmed In Old California there — the first film to be shot in that community. In 1911, Nestor Film Company opened Hollywood’s first film studio at the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Gower Street. The studios often employed Japanese landscapers and gardeners and occasionally Japanese actors. Although Japanese who appeared on-screen were usually relegated to small, uncredited roles, there were a few Japanese leads. The first Japanese to appear in an American film was Tokuko “Taku” Nagai Takagi, who came to the US in 1906 and ultimately appeared in four films. The most famous was Sessue Hayakawa (né Kintaro Hayakawa).

After being expelled from a Japanese naval academy, Hayakawa studied at the University of Chicago, where he studied political economics and played American football. After graduating, he moved to Los Angeles, where he began acting at a theater in Little Tokyo, appearing in a production of The Typhoon with Tsuru Aoki, whom he later married. He then starred in a successful film version, directed by Thomas H. Ince, who followed it up with two more films starring Hawakawa in 1914. In 1915, he starred in The Cheat, directed by Cecil B. DeMille.

In The Cheat, Hayakawa played a villainous merchant who assaults and brands a married white woman in order to claim her as property. Not surprisingly, members of the Japanese community objected to the unflattering portrayal and when the film was re-released, the character’s nationality was changed to Burmese. Meanwhile, members of the white community were evidently concerned by Hayakawa’s popularity with white women. Despite — or because of — the controversy, the film was a financial success and afterward, Hayakawa earned $5,000 per week (about $125,000 adjusted for inflation). Embracing his role as a movie star, he purchased a gold-plated automobile. Hayakawa’s stardom would prove to be short-lived, however, and Hayakawa left Hollywood in 1922 to work in European and Japanese films before making a comeback of sorts with Hollywood films like Tokyo Joe (1949) and Bridge on the River Kwai (1957).

Given the anti-Japanese hostility in the Hollywood district, it’s somewhat surprising that the focus of yellow peril hysteria on-screen was mostly limited to Chinatown mysteries, in which long-clawed Chinese sometimes enslave white women and put them to work in their secret opium dens. Japanese-American actors, in contrast, usually portrayed either Japanese or Native American protagonists in romantic melodramas — often produced by Haworth Pictures Corporation, the company started by Hayakawa and director William Worthington.

Films starring Japanese actors about Japanese subjects of the era include The Oath of Tsura San (1913); The Ambassador’s Envoy, The Courtship of O San, The Curse of Caste, The Geisha, Nipped, O Mimi San, A Relic of Old Japan, The Typhoon, The Vigil (all 1914); The Cheat and The Famine (both 1915); Alien Souls, The Honorable Friend, The Soul of Kura San, and The Yellow Pawn (all 1916); The Call of the East and Hashimura Togo (both 1917); The Bravest Way, Her American Husband, His Birthright, The Curse of Iku, and The Japanese Nightingale (all 1918); and Bonds of Honor, The Dragon Painter, and The Gray Horizon (all 1919).

Most of the Japanese associations and institutions established in the era were decidedly more positive than the racist, protective associations formed by some of their would-be white neighbors. By 1910, there were two additional newspapers serving the Japanese community: Rafu Ashai and publisher Keitarō Sugiyama‘s Daitetsu Shinbun (later renamed Heimin (“common people”) and finally, Rafu Mainichi Shinbun).

The Koyasan Beikoku Betsuin opened in 1912 at its original location. There were several Japanese banks by the mid-1910s in Little Tokyo. In 1918, the Japanese Union Church formed and Fukui Mortuary opened in its original location. It was also that year that a group of Japanese physicians re-opened the former Turner Street Hospital as the Southern California Japanese Hospital.

In 1920, the California Alien Land Law — which already prohibited Japanese from becoming citizens, owning property, or even signing long-term leases — was amended to ban even short-term leases. The Cable Act of 1922 made it so that any person who married a Japanese resident alien would as a result actually lose his or her American citizenship.

Takao Ozawa, a man who’d lived in the US for 20 years, filed for naturalization — which was then limited to either “free white” people or those of “African nativity and descent.” Ozawa decided to challenge the Naturalization Act of 1906 on behalf of the Japanese, which he quite reasonably argued fit all objective definitions of “free white persons.” Justice George Sutherland, however, ruled that “white person” applied only to members of the Caucasian race. A couple of months later, the same justice ruled similarly in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, when a Sikh immigrant argued that Punjabis are, in fact, members of the Caucasian race. In the aftermath of both decisions, racists were emboldened and the Asiatic Exclusion League lobbied successfully for the Immigration Act of 1924. It passed and as a result, almost all non-northern Europeans were barred from immigration until 1968. Japanese migrants thus began overwhelmingly favoring Brazil over the US and São Paulo is still home to the largest population of Japanese outside of Japan.

Even with the Japanese barred from immigrating, the Japanese population grew thanks to internal migration and new births. By 1920, Los Angeles County was home to 19,911 Japanese (with 11,618 living in the city). By 1923, a quarter of the nation’s Japanese lived in Los Angeles. By then, Japanese-Angelenos were employed in a variety of occupations. They were, in descending order, produce vendors, motor truck operators, grocers, lodging operators, wholesale dealers, candy store operators, restaurant workers, barbers, and garage mechanics. Japanese women, by the 1920s, made up 70% of the state’s midwives. In 1925, the California Bureau of Child Hygiene began licensing maternity hospitals and maternity homes, many of which were run by Japanese midwives. Other Japanese institutions in operation by the 1920s included language schools, department stores, drug stores, ice cream parlors, jewelry shops, ice cream parlors, temples, and churches (by 1927 there were nineteen).

The other Japanese nihonmachi were also thriving and new ones emerging. By 1927, Uwamachi’s population was estimated to have reached around 200. An enclave, known as Seinan, arose just west of USC in the West Adams district. Around 1920, it was home to about 100 Japanese. By the end of the decade, it was the third most populous Japanese enclave.

The second most populous Japanese enclave was Furusato. Furusato was a fishing village located on Terminal Island’s Fish Harbor. Before the Japanese, the fishing industry was dominated by Italians and focused on small fish, like sardines, which were soon driven into local extinction through over-hunting. In San Diego‘s Little Italy and San Pedro, the Japanese moved boats into deeper waters in pursuit of tuna — a fish until then dismissed as a “trash fish” by most Americans. Following the newfound taste for tuna, large canneries sprang up on the island. Japanese institutions in the community included Fisherman’s Hall, candy stores, grocery stores, pool halls, and a Shinto shrine.

Another Japanese enclave arose in the community of Sawtelle, or “Soteru.” Sawtelle was an independent community until 1922 when it consolidated with Los Angeles. Many Japanese gardeners settled there who worked on estates in Bel Air, Beverly Hills, and Brentwood — where they were in demand as landscapers but not allowed to actually live. By 1941, the surrounding area would be home to 26 Japanese-owned nurseries. In 1926, Hiroshima-born Riichi Ishioka established the Kobayakawa Boarding House on Sawtelle. After several expansions, it was at its peak home to 60 Japanese gardeners. It remained in operation until 1979.

Although not the most populous Japanese enclave, nor one even dominated by Japanese, Boyle Heights was unquestionably amongst the most vibrant. During the 1920s, the Japanese footprint of Little Tokyo had expanded east along 1st Street into the Eastside neighborhood of Boyle Heights. Boyle Heights was then highly diverse — home to large numbers of Jews, Croats, Mexicans, Russians, and Serbs, among other non-WASPs, then excluded from most of Los Angeles. Whereas Little Tokyo was home to a diverse collection of Japanese businesses, Boyle Heights was overwhelmingly residential and suburban, with Japanese institutions for the most part limited to a couple of grocery stores, several churches, schools, and a hospital.

The hospital was the Japanese Hospital, funded by a group of Japanese physicians: Kikuwo Tashiro, Daishiro Kuroiwa, Fusataro Nayaka, Toru Ozasa, and Matsuta Takahashi. Tashiro had, in 1927, prevailed in the US Supreme Court case, Jordan vs. K. Tashiro. As a result, a new, 42-bed hospital, run by Japanese, was constructed. Its Art Deco design was created by Yos Hirose, a local architect who’d moved to Los Angeles after obtaining his bachelor’s degree from the Armor Institute of Illinois around 1915. A few years after opening, in 1935, the older Southern California Japanese Hospital closed its doors and merged with Boyle Heights’ Japanese Hospital. In 2016, the former Japanese Hospital would be designated City of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 1131.

In Hollywood, the Hollywood Protective Association was formed to harass a group of five

or so Japanese who’d purchased lots along a block of Tamarind Avenue. The final straw for the protective association was the construction by the Japanese of a church. The anti-Japanese Hollywood residents ultimately prevailed. The church was gone by 1927 and no vestiges of the budding enclave remain today.

Things weren’t much better in the Hollywood film industry for Japanese actors. Among the only movies with roles for Japanese were the melodramas A Tokyo Siren (1920) and Sen Yan’s Devotion (1924) — both of which starred Tusu Aoki. After Sen Yan’s Devotion, Aoki retired from acting and moved out of the US with her husband.

In the 1930s, Japan continued to pursue its imperial ambitions. In 1931, Japan conquered Manchuria and established the puppet state of Manchukuo. In response, the League of Nations did nothing to check the aggression. Japan, on the other hand, withdrew from the organization, which quickly began to fall apart. In 1937, Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China — the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Despite the US ban against Japanese immigration entering its seventh year, the Japanese population of Los Angeles County grew to 35,390 (the city was home to 21,081). Jews began leaving Brooklyn Heights and City Terrace for newly developed suburbs. As the Jews left Brooklyn Heights, daily usage of that name faded and the district came to be simply regarded as another area of Boyle Heights. At the same time, as the city spread west, what had been known as Uptown came to be more commonly characterized as Midtown.

There were several new Japanese-American institutions created in the 1930s. In Uwamachi, Rafu Uwamachi Daini Gakuen (founded in 1915) established the Young Men’s Meeting House (later also home to a Japanese language school) in 1930. In 1931,

the still extant St. Mary’s Japanese Episcopal Church was constructed around the corner. In 1931, Koichi Kawana designed a Japanese garden for Stoner Park in Sawtelle. In Little Tokyo, in 1934, the annual Nisei Week festival was inaugurated. In Boyle Heights, Shigeo Takayama, President of the Roosevelt High School Japanese Club, led efforts to create the high school’s Japanese garden, Heiwa En, or “Garden of Peace.” In 1938, Shūji Fujii launched the communist Japanese-English newspaper, 同胞 (or Dōhō; meaning “comrade”). In the late 1930s, construction took place of Boyle Heights’ Tenrikyo Junior Church of America, the Konko Church, and the Rafu Chuo Gakuen School.

By 1940, the Japanese population of Los Angeles County had grown to 36,866 (with 23,321 living in the city). Hostilities between the empires of the US and Japan reached their breaking point in December 1941, when Japanese planes attacked American military outposts in the American-occupied territories of Hawaiʻi and the Philipines. In the weeks that followed, over 1,000 prominent Japanese-Americans (businessmen, clergy, teachers, &c) were arrested by the FBI and other law enforcement agencies. Japanese businesses were boycotted and after Mayor Fletcher Bowron spread the rumor that Japanese-American employees of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power were planning on poisoning the city’s water supply, most Japanese were fired from their jobs.

Over two months later, Executive Order 9066 was passed which resulted in the forced relocation and incarceration of roughly 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry in ten concentration camps. The largest assembly center used to incarcerate Japanese-Americans was at Santa Anita Park. For several months in 1942, 18,719 people lived in the park’s horse stables and newly-constructed barracks. The Santa Anita Assembly Center closed on 27 October 1942. A plaque memorializing the events of wartime Santa Anita was installed in 2001.

During the Japanese Interment, care of many Japanese businesses was overseen by non-Japanese. Those that were not were often the targets of vandals. A congregation of Latino evangelicals temporarily took over Konko Church and Tenrikyo was adopted by a congregation of black Christians. On the other side of the Los Angeles River, Little Tokyo transformed into Bronzeville, a vibrant black enclave that thrived despite overcrowding — the inevitable result of recruiting southern blacks to work in the war effort and simultaneously prohibiting them from living anywhere in all but a few already cramped neighborhoods like South Central and the newly vacant Little Tokyo.

In March 1945, US forces firebombed Tokyo, displacing roughly a million people and killing an estimated 120,000. On 6 and 9 August, the US became the only country to use nuclear weapons in the history of armed conflict when it dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing as many as 260,000 people. On 9 August, the USSR declared war on the Empire of Japan and on 2 September, Japan surrendered.

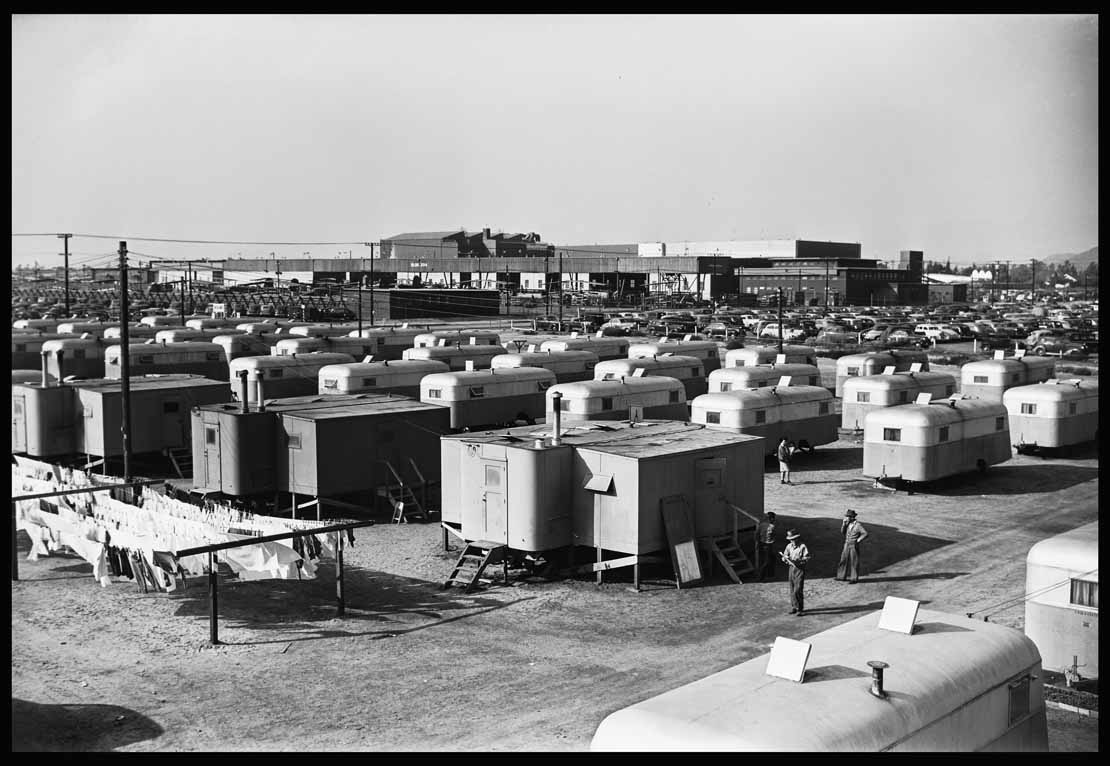

In December 1944, President Roosevelt suspended Executive Order 9066 but the last of the concentration camps didn’t close until 1946. Years of difficult resettlement followed. Many returning Japanese found their gardens had been intentionally destroyed, their businesses vandalized, and some faced violent harassment. At least two Japanese who moved back to Boyle Heights had their homes burned down. Many others stayed in bare-bones trailer camps in the San Fernando Valley — such as the Winona camp in Burbank — and ultimately settled in nearby neighborhoods. Many more moved to South Bay suburbs like Gardena, Torrance, and Palos Verdes in order to work in the nearby aviation and aerospace industries — and where housing restrictions against Japanese were fewer. Some Japanese also moved to the San Gabriel Valley — choosing to settle in communities like Monterey Park, Pasadena, and San Gabriel. Others still ventured into Maravilla, Montebello, Orange County, and South Los Angeles‘s Crenshaw district.

More than a few Japanese returned to Little Tokyo/Bronzeville and Boyle Heights where, for a time, many stayed inside their businesses, temples, and hostels, like the Evergreen Hostel, which the Boyle Heights Language School re-opened as in 1945. Despite the fact that neither neighborhood would never see the restoration of pre-war vibrancy, many new businesses opened in Little Tokyo and cultural expressions resumed. In 1949, Nisei Week festivities returned.

New, post-war Japanese businesses in Boyle Heights were fewer and further between. Nevertheless, Haru Florist, (“haru” or “春” is Japanese for “spring”) was founded by Henry “Hank” Nobu Yoshimizu and Ruth Yoshimizu in 1954. Hank passed away in 2004 but Ruth is still alive at 95 years old. Today the shop is run by their daughter, Karen Nobuta, with assistance from Karen’s daughters, Cheryl and Melanie. Located as it is near Evergreen cemetery, Haru is especially popular with Japanese-Angelenos paying respects to their ancestors there.

As the returning Japanese population dispersed across the Southland, printed media naturally provided some of the social glue which held the diaspora together. In 1947, a new community newspaper billed as “new Japanese American news” was also launched, Shin Nichibei (not to be confused with the earlier San Francisco publication of the same name). It remained in publication until 1966. A more surprising social unifier, perhaps, was the rise in popularity of baseball amongst Japanese-Americans. Many viewed this slowly-paced, cricket-derived game with roots in 18th-century England as more American than traditional Japanese sports like judo, kendo, and sumo. Japanese-Angelenos formed baseball teams like the Little Tokyo Giants and LA Tigers to compete against other Japanese-American teams.

On 30 May 1949, the 442nd Infantry World War II Memorial was installed in Boyle Heights’ Evergreen Cemetery. The 442nd Infantry, also known as the “Go for Broke” Regimental Combat Team, was comprised entirely of Japanese volunteers from Hawaii. Unlike their American mainland counterparts, most Hawaiian Japanese were not incarcerated and were even allowed to fight in the US military. Hawaii only became a state in 1959. The unit was the most highly decorated in combat history. They also suffered the highest casualties of any unit in the war, with over 600 killed and 9,486 wounded.

The 1950s brought significant changes to Japan and also were the decade in which Japanese popular culture spread around the world. The Allied occupation of Japan ended in 1952. The economy quickly recovered as the focus turned from agriculture to industrial. By 1955, the economy had surpassed pre-war levels, unleashing the so-called “economic miracle.” Japan became a member of the United Nations in 1956. In 1951, Akira Kurosawa‘s film Rashōmon won the prestigious Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, reflecting a growing awareness of Japanese films by non-Japanese critics. In 1956, a heavily re-edited version of Ishirō Honda‘s 1954 film Gojira, was released in American cinemas as Godzilla, King of the Monsters! Its popularity reflected a growing awareness of Japanese films amongst mainstream filmgoers.

By 1950, the Japanese population of Los Angeles County had shrunk to 36,761 but within the city it had grown to 25,502. Many would-be homeowners in Boyle Heights longed to live elsewhere, as the banks had redlined the entire neighborhood, making it all but impossible to get home loans. From 1954-1957, the 101, 5, and 10 freeways all carved their way through Boyle Heights, in the process decimating commercial areas, displacing thousands of residents, and filling the air with noise and pollution.

In 1952, Boyle Heights resident Sei Fujii challenged the Alien Land Laws which prevented him from purchasing a home in City Terrace. He prevailed, in Sei Fujii v. California. A year later, the US Refugee Relief Act passed, which stated that immigrants who could demonstrate evidence of a job and home could become citizens. As a result, 40,000 first-generation living in Los Angeles were finally able to naturalize as citizens between then until 1965.

Even though the Japanese population was leaving Boyle Heights, many returned regularly to visit the neighborhood’s temples. So many, in fact, that two relocated across the river to larger facilities in Little Tokyo. In 1958 and ’59, Japanese automobile manufacturers Toyota, Datsun, and Honda all began selling vehicles in Los Angeles. It’s likely, therefore, that some of these commuting congregants drove newly-purchased Japanese cars along the newly completed freeways, the construction of which had helped close the chapter on Japanese Boyle Heights.

Little Tokyo was also encroached upon by redevelopment. First, a block of Little Tokyo was razed to clear the path for an extension of the Civic Center. In 1953, roughly 1,000 residents of Little Tokyo were displaced to clear the way for the construction of the Police Administration Building (later renamed the Parker Center and currently slated for demolition). As a result, about one-fourth of the neighborhood’s commercial property was also lost, which further pushed the occupational trend away from wholesale into horticulture and floriculture. Many Japanese women, at the same time, found work in the garment industry.

Away from Boyle Heights and Little Tokyo, Japanese enclaves thrived. Soteru witnessed the establishment of new nurseries — buoyed in part by a resurgence of interest in Japanese landscape design, which many felt complimented mid-Century Modern architecture. In 1950, George and Grace Izumi opened the long-running Grace Bakery Shoppe on Jefferson Boulevard in Crenshaw. In J. Flats, the Japanese Presbyterian Church was built in 1955. A Japanese shopping center called Town and Country opened in Gardena in 1955 (it was later renamed Kyoto Plaza and is now known as Seoul Plaza). In 1956, Westview Construction built on South Bronson and South Norton avenues in the Crenshaw District with Japanese architectural details aimed at Japanese-American buyers. In Pacoima, the Kazumi Adachi-designed San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center was built. Adachi was one of several local Japanese-Angeleno architects active at the time.

In 1956, a couple remembered today only as “the Setos,” opened Otomi Café, today the oldest extant Japanese restaurant in Los Angeles (and probably Southern California). Their choice of name was perhaps inspired by enka singer Hachiro Kasuga’s hit song “お富さん” (Otomi-san), which by the previous year had sold over a million copies. In the early 1970s, Otomi was purchased by Aki and Tomi Seino, who apparently renamed it Otomisan. After Aki died in 2005, Tomi closed shop. Six months later it was purchased by the owner of a nearby dry cleaner, Yayoi Watanabe.

The Fuji-kan Theater, which opened in 1925, was likely Los Angeles’s first Japanese cinema. In January 1942, the owner was arrested for screening Japanese newsreels. Towards the end of the Bronzeville era, it opened as the Linda Lea Theater, a venue that featured live music and films aimed at a black audience as well as the house band, Sammy Yates and his Linda Lea Orchestra. By 1951, it was screening Japanese films by Daiei Films (大映映画株式會社). In 1952, it became Nichibei Kinema (which re-opened as Kinema in 1955). Kinema closed in 1964 when ThriftyMart bought the property.

By then — the Golden Age of Japanese Cinema — there were several Japanese cinemas, each associated with a particular Japanese film studio. The Kokusai Theater (c. 1953-1986) showed films by Daiei at a Crenshaw theater owned and managed by Moto Yokoyama. In 1955, the New Linda Lea Theater took over Downtown’s Aztec Theatre and by 1957 it was a showcase for Toei Films (東映株式会) until around 1965 when it began showing Kung Fu films. Kinema’s owner operated Kinema East (1964-1972) in Boyle Heights, which showed films of Nikkatsu (日活株式会社). Toho Co (東宝株式会社) films were screened at Toho La Brea (1960-c. 1974) while the second story was home to a restaurant called the Cherry Blossom. The Kabuki Theatre screened films by Shochiku Films (松竹株式会社) from 1964 until 1973.

More Japanese culture and pop culture made their way onto American television sets in the 1960s. In 1964, Tokyo hosted the Summer Olympics. It was the first time the Olympics were held in Asia. They were also the first Olympics to be telecast live, using a communication satellite. A year earlier, NBC began broadcasting re-runs of 鉄腕アトム (Tetsuwan Atomu), dubbed in English and re-titled Astro Boy — providing most Angelenos with their first taste of Japanese animation, which came to be known in the US as anime. It wouldn’t be the last — even in the decade — and a few years later マッハGoGoGo (Mach GoGoGo) was shown in syndication as Speed Racer.

The Japanese population of Los Angeles County rose to 77,314 — the city’s population grew to 51,468.

At the VA West Los Angeles Medical Center, well known-garden designer Shinichi Maesaki (1913-1996) designed a Japanese garden to be cared for as part of an occupational therapy program for veterans.

Back in Boyle Heights, Thomas Tsunetomi Noguchi was appointed deputy coroner for Los Angeles County in 1961. In 1967, he became Chief Medical Coroner and was a familiar figure in Los Angeles who came to be known as the “coroner to the stars.” Among the many high-profile autopsies with which he was involved were those of Gia Scala, John Belushi, Marilyn Monroe, Natalie Wood, Robert F. Kennedy, Sharon Tate, and William Holden. Across town from Boyle Heights’ Los Angeles County Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner offices,

In 1964, Leo Hayashi founded Hayashi Realty in Boyle Heights. Tenrikyo Church established a judo program — then in its first year as an Olympic Sport. On 27 November 1966, a memorial known as Garden of the Pines was installed in Evergreen Cemetery, dedicated “to the memory of the Issei Pioneers.” Despite those developments, however, the Japanese exodus from Boyle Heights continued. Although the US Supreme Court had declared racial housing covenants illegal in 1948, race-based housing restrictions meaningfully eased in 1963, after the passage of the Fair Housing Act.

Other suburban Japanese enclaves witnessed the foundation of new Japanese businesses. For example, the architecture firm of O’Leary Terasawa Partners designed the Bank of Tokyo of California in Crenshaw in 1965. It was the South Bay, though, that would emerge as the primary suburban residential, commercial, and corporate enclave for Japanese Los Angeles. In 1960, Nissan Motor Corporation USA established its headquarters in Gardena. Toyota and Honda followed suit (although Nissan and Toyota have since relocated to other states).

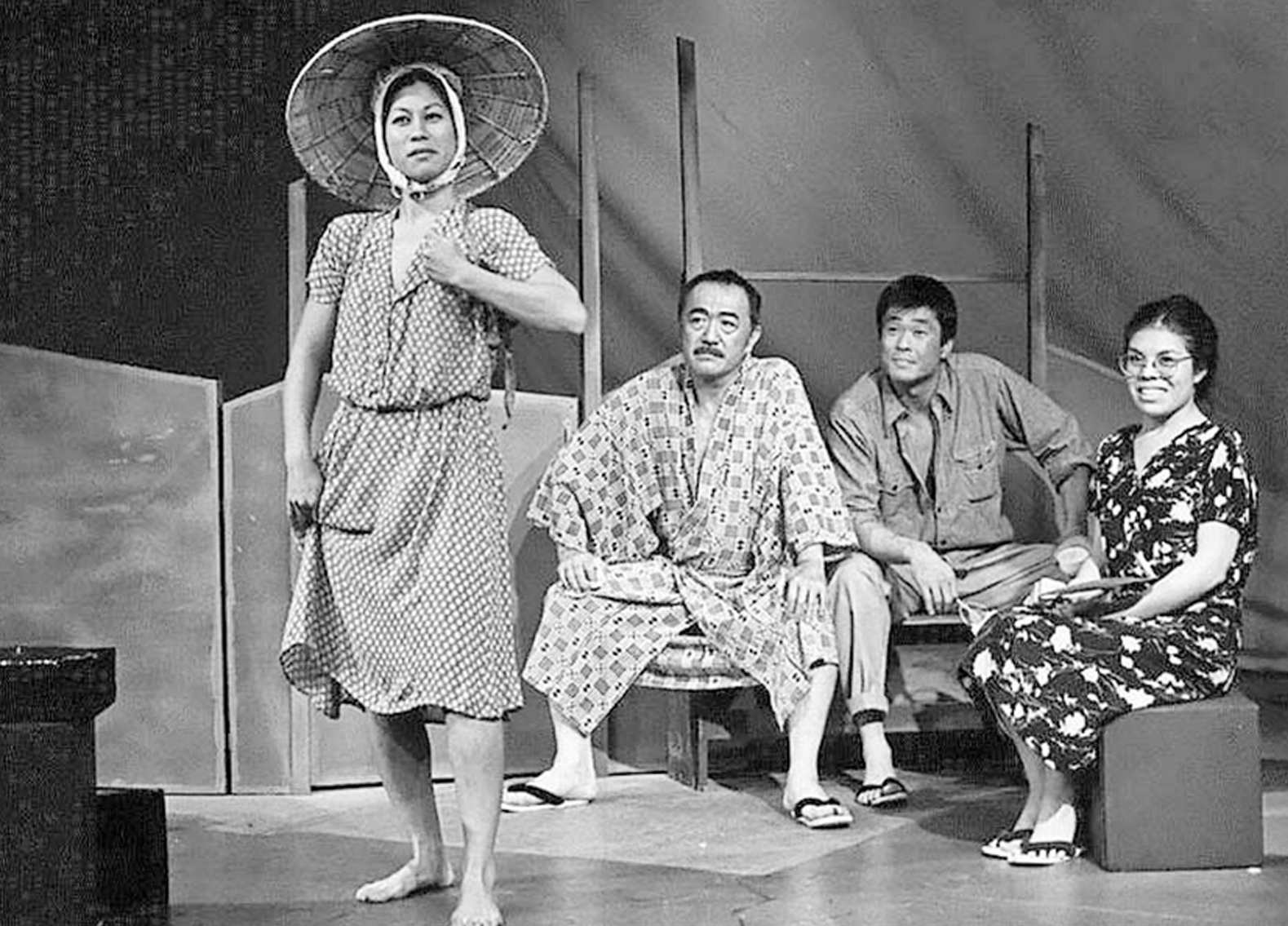

The decades which followed Sessue Hayakawa and Tsuru Aoki’s departures from Hollywood were not good ones for Japanese film actors. Films set in Japan were all but not existent except for a couple of anti-Japanese propaganda films (which employed Chinese actors to play Japanese villains). Actors including Mako, Miyoshi Umeki, and Pat Suzuki found occasional work in Hollywood films like The Crimson Kimono, Geisha Boy, House of Bamboo, I Was an American Spy, Japanese War Bride, Sayonara, The Teahouse of the August Moon, and Tokyo After Dark. Shows like Hawaii Five-O and Star Trek sometimes featured Japanese-American actors, the latter most notably making a star of George Takei. But whilst Los Angeles at one point supported five cinemas that exclusively screened Japanese films in the 1960s, there were relatively few opportunities for Japanese Americans in film, so many turned to theater.

There was a theater in Little Tokyo before, and the Chop Suey Circuit had thrived from the 1930s-1950s, but modern Asian-American Theater was essentially born with the formation of East West Players (EWP) in 1965 by a multi-ethnic group of Asian-American actors. Soon other Asian-American theatre companies sprang up in San Francisco, New York City, and Seattle. Most of the playwrights who wrote the plays that came to form the basis of the Asian-American theater repertoire were Japanese-American, including Edward Sakamoto, Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Momoko Iko, and Wakako Yamauchi. In 1996, EWP moved from their original home at Bethany Presbyterian Church in Silver Lake to Union Church in Little Tokyo.

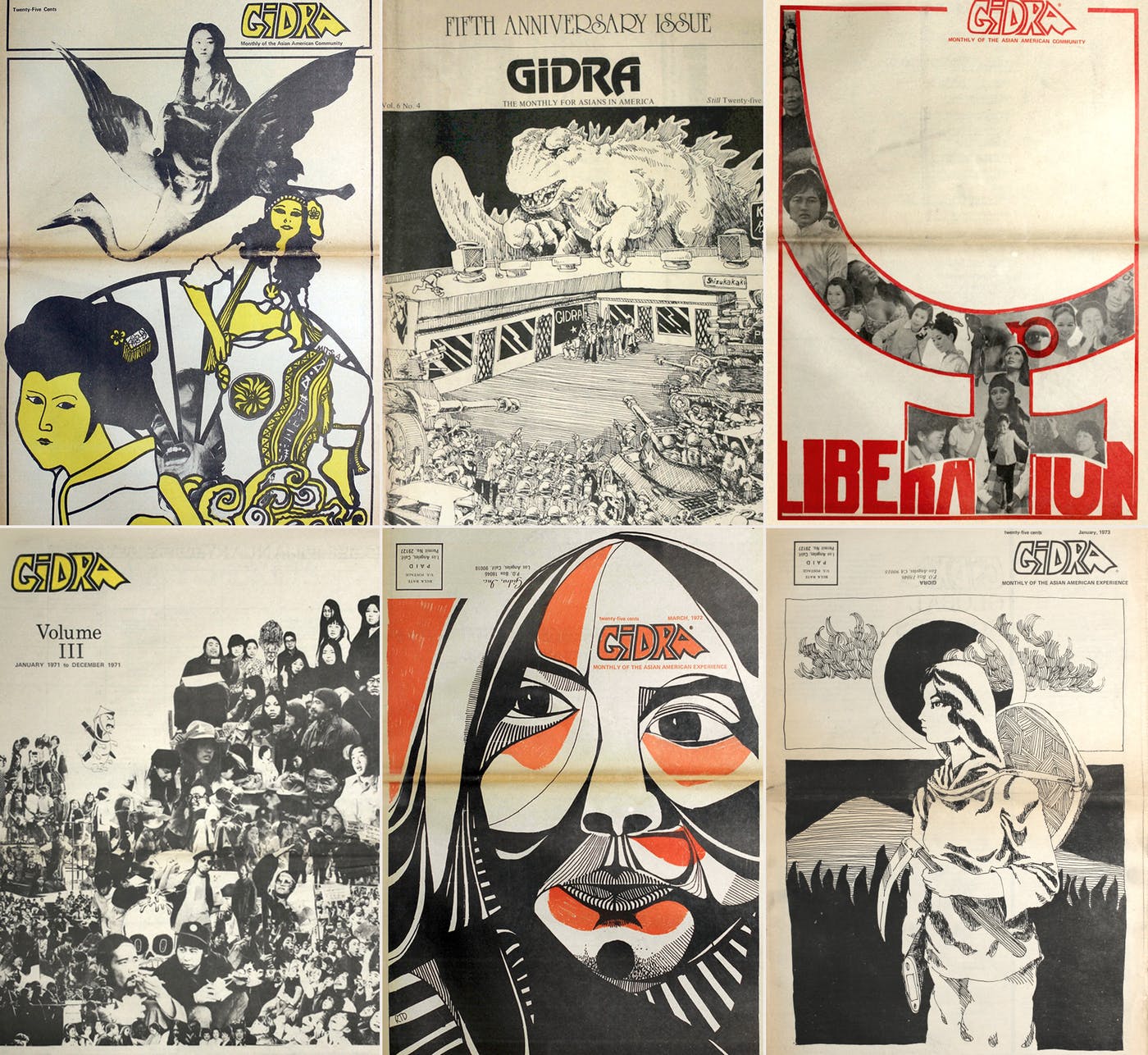

The Immigration Act of 1965 (enacted in 1968) ended racial quotas, opening the doors for immigrants from Africa, Asia, and elsewhere. The Asian population of Los Angeles, until then mostly Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese afterward grew more diverse. Activist, historian, and UCLA alumnus Yuji Ichioka coined the term “Asian American” as a blanket term. In April 1969, a group of UCLA students launched the newspaper Gidra, billed as the “voice of the Asian American Movement.” Gidra ended publication in 1974. 50 years after its launch, however, it was relaunched in 2019.

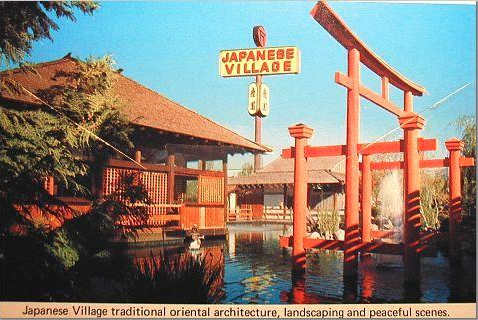

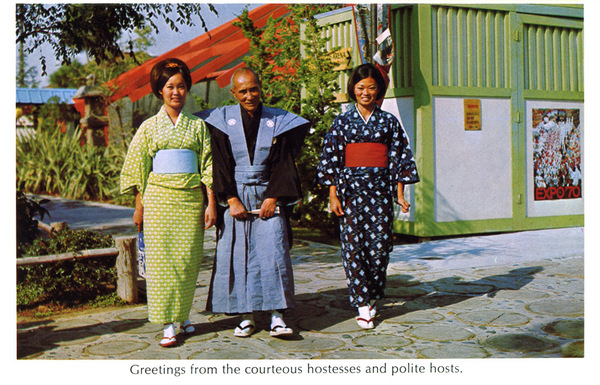

The Japanese Village and Deer Park was a Japanese theme park that opened in Buena Park in 1967. It was created by Allen Parkinson, who also owned the Movieland Wax Museum in Buena Park and who, obviously, was not Japanese. Nevertheless, the park hired and attracted Japanese and aimed for something like authenticity. It featured performances, traditional Japanese architecture, exhibits, and freely-roaming deer — inspired by Japan’s famous Nara Park. Attractions included a tea house, the Dove Pavilion, Home of the Fuji Folk, koi ponds, a Japanese garden, pearl divers, and captive dolphins that performed in the Sea Theater. Parkinson sold the park in 1970 to a firm from Newport Beach. It was twice featured on the CBS television program, Mannix, in 1971’s “Overkill” and 1974’s “Enter Tami Okada.” The park was purchased by a subsidiary of Six Flags, which began euthanizing the deer. Nearly 200 were killed before authorities stoped them from killing any more. The park closed in 1975. A second park, Enchanted Village, opened in its place in 1976 but closed in 1977. It was subsequently demolished and replaced with an office park.

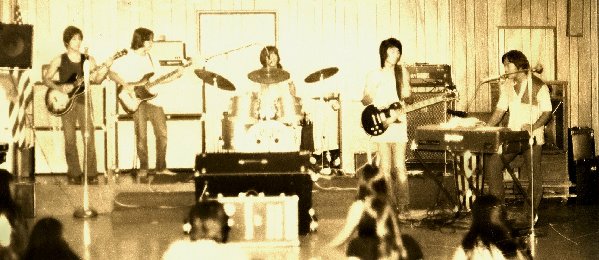

An overlooked and under documented but fascinating era in Los Angeles music was the sansei dance band era that began in the late 1960s and flourished in the 1970s. In that era, sansei teenagers (and a few non-Japanese including quite a few Chinese) formed dance bands like Beaudry Express, Benjo Blues Band, Carry On, The Chosen Few, Crossroads, The Dynasty Band, Easy Livin’, Free Flight, Headstone, Just Us, Local Mojo, A Long Time Coming, Prism, The Prophets, The U.N., We the People, and Winfield Summit.

The kings of the scene, it seems to be conceded amongst most who were there, were The Prophets — a ten piece band that included six Japanese members and four non-Japanese. They, and other dance bands, played covers of Funk, R&B, Rock, and Soul for Japanese teenagers venues like the Japanese Village and Deer Park, Blarney’s Castle, Gardena’s The Phrog, Rodger Young Auditorium, and the Parkview Women’s Club. Members of several bands later joined The Music Company, a sansei dance band that has continued to play into the 2010s. These sansei dances offered teenagers from throughout Metro Los Angeles to mix and mingle away from the home. Elisabeth L. Uyeda‘s blog, Summer Sun: the Los Angeles Asian American Dance Scene, is one of the few online documents of the scene.

In the 1970s, West Germany and Japan — World War II’s losers — overtook the US and other countries which experienced slowing economic growth rates and recession. In 1970, Japan’s economy surpassed West Germany’s and became the world’s leader in industrial manufacturing. As a result, Japanese firms began to expand into new territories, bringing with them a new wave of Japanese immigrants. In 1972, Japan launched its first satellite. Japanese cuisine began to, for perhaps the first time, make significant in-roads with non-Japanese Angelenos. in 1972, the first Benihana (founded in New York City by Hiroaki Aoki) opened in Beverly Hills (and remained in operation until 2015). At the end of the decade, a less-celebrated Japanese chain, Yoshinoya, opened its first location in Los Angeles (albeit under the moniker, The Beef Bowl.) Kouraku, a non-chain Japanese restaurant, was the first ramen restaurant in the US and has been in operation since 1976. Sushi chefs began using avocado as an ingredient in “California rolls.” In 1982, Takara Sake USA Incorporated introduced the now ubiquitous American sake brand, Sho Chiku Bai.

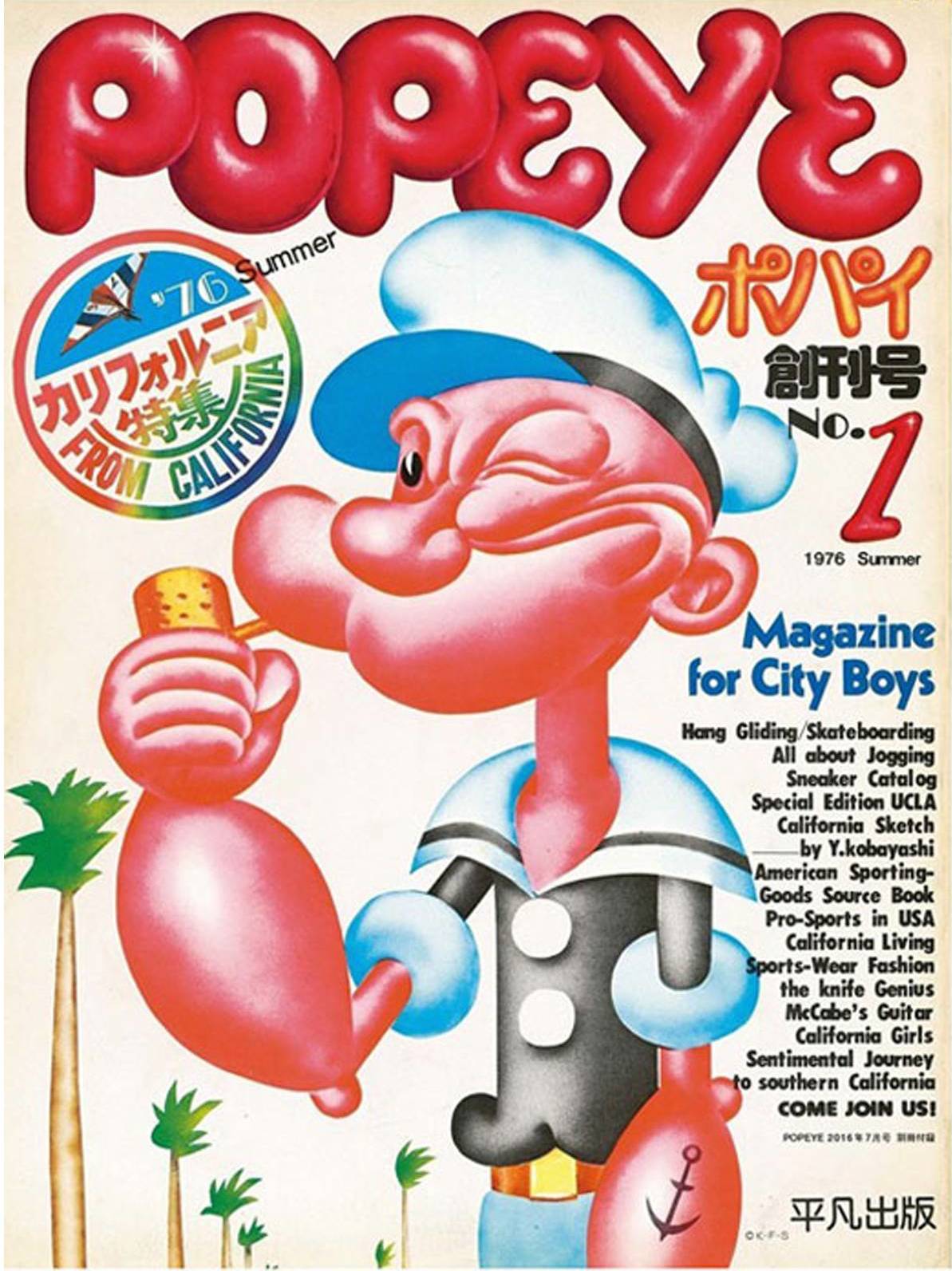

Many Japanese figures and products made their way to Los Angeles in the 1970s. The global popularity of high mileage Japanese cars exploded following the oil crisis of 1973. In 1975, Emperor Hirohito visited Los Angeles — but not any Japanese enclaves — choosing instead to pop into Disneyland and the Music Center. In 1976, an inarguably more popular Japanese character came to the US for the first time, Hello Kitty, which spawned a chain of boutiques called Sanrio Surprise. The Roland MC-8 Microcomposer was introduced in 1977 and was used to excellent effect by Yellow Magic Orchestra on their 1978 debut, which in turn influenced generations of electrofunk and hip-hop producers. It was also in 1978 that Sony introduced the Walkman. In 1977, the first Little Tokyo location of Books Kinokuniya (紀伊國屋書店) opened, where one might buy manga, Japanese books, and magazines like Popeye (and later the much-missed Free & Easy). Construction began of LACMA‘s Pavilion for Japanese Art in 1978 (it was finished in 1988).

By 1970, the Japanese population had risen to 104,078 in the county and 54,878 in the city. By the 1970s, the percentage of marriages between Japanese and non-Japanese Angelenos had grown from 29.5% in the 1960s to 39%. Although most of the Japanese had dispersed from the city’s traditional Japanese enclaves, elderly Japanese in Los Angeles witness the Jewish Home for the Aged transform into the Keiro Retirement Home in 1975. In 1976, the aforementioned Popeye, — a “magazine for City Boys,” launched and chose to devote its inaugural issue to Los Angeles and the curious pastimes of the city, such as jogging.

By 1970, the Japanese population had risen to 104,078 in the county and 54,878 in the city. By the 1970s, the percentage of marriages between Japanese and non-Japanese Angelenos had grown from 29.5% in the 1960s to 39%. Although most of the Japanese had dispersed from the city’s traditional Japanese enclaves, elderly Japanese in Los Angeles witness the Jewish Home for the Aged transform into the Keiro Retirement Home in 1975. In 1976, the aforementioned Popeye, — a “magazine for City Boys,” launched and chose to devote its inaugural issue to Los Angeles and the curious pastimes of the city, such as jogging.

The Little Tokyo Redevelopment Project was adopted by the Los Angeles City Council on 24 February 1970. In 1973, The Little Tokyo People’s Rights formed to challenge evictions wrought by the redevelopment, often at the hands of Japanese developers like the Kajima Corporation‘s East-West Development Corporation, created the same year. In 1974, the Little Tokyo Anti-Eviction Task Force organized a protest against the construction of the New Otani Hotel, the destruction of the Sun Hotel, and the eviction of its tenants. Nevertheless, construction of the New Otani and Weller Court began in 1976. In 1977, the Friends of Little Tokyo Arts formed to promote the integration of public art into Little Tokyo redevelopment.

Representation of Japanese and other Asian-American improved somewhat in the 1970s. In 1970, Robert Akira Nakamura founded Visual Communications, which is today the oldest community-based media arts center in the US. In 1972, he made the documentary Manzanar. The first television show with an all-Asian cast was 1972’s The Amazing Chan and the Chan Clan. Although the family depicted in the Hanna-Barbera cartoon were Chinese-Americans, their voices were in half the cases provided by Japanese-American actors, including Beverly Kushida, Brian Tochi, Leslie Kumamota, Michael Takamoto, Robert Ito, and Robin Toma. The short-lived Mr. T and Tina starred Pat Morita, who in the 1980s starred in the series, Ohara. In 1977, PBS aired a television adaptation of Wakako Yamauchi’s And the Soul Shall Dance. In 1986, Gedde Watanabe, Patti Yasutake, Rodney Kageyama, Sab Shimono, and Scott Atari appeared on the sitcom, Gung Ho.

Excerpt: Cruisin’ J-Town by Duane Kubo

Dan Kuramoto founded the Asian-American jazz group, Hiroshima, in 1974, featuring himself on wind instruments, Danny Yamamoto (drums), Dave Iwataki (keyboards), Johnny Mori (percussion and taiko), June Kuramoto (koto), Nancy Sekizawa (née Matoba) on vocals, and Peter Hata (guitar). All were Los Angeles natives except Kuramoto, who moved to the city at a young age from Saitama Prefecture. They released their debut in 1979 and later transitioned into smooth jazz and new age territory.

The Atomic Café had opened back in 1946 and was operated by Ito and Minoru Matoba. Around 1977, it became a popular hang out for punks after the Matoba’s daughter, Atomic Nancy covered the interior walls with fliers and posters for punk bands and filled the jukebox with a mix of punk, new wave, classic rock, standards, and Japanese music. The Atomic Café stayed in business until 1989. The building which housed it was demolished in 2015 to make way for the new Little Tokyo/Arts District Station.

In 1975, Iwasaki Images of America began making the plastic food seen in Japanese restaurant display windows. Founded in Torrance, it later moved to Gardena and was featured on Visiting with Huell Howser. In 1975, Osaka-based Marukai established one of the first modern Japanese supermarket chains in Los Angeles and established its headquarters in Gardena.

By the 1980s, the manufacturing industry had largely relocated from countries like Japan to China, Mexico, Korea, Thailand, and Taiwan but the economies of West Germany and Japan showed few signs of slowing, which resulted in a great deal of amongst American adults of Japan (but none of Germany). Nevertheless, Tampopo, when released in 1987, proved more popular with a segment of American filmgoers than any Japanese film in some time. American children, meanwhile, were seemingly more open to Japanese culture, embracing Transformers (adapted from Takara‘s Diaclone and Microman lines and launched in 1984), the Nintendo Entertainment System (introduced in Los Angeles in 1985), Studio Ghibli (founded in 1985), anime series like Robotech (adapted from The Super Dimension Fortress Macross, Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross, and Genesis Climber MOSPEADA), and all things ninja related.

Los Angeles was positioned at the crossroads of Japanese and American culture. Since the 1950s, the Port of Los Angeles had received more tonnage of Japanese imports and any other port in the world and Japanese-Angelenos were thus well established in the import-export business. The Japanese population of Los Angeles had grown, in 1980, to 116,543. Amongst some Angelenos I know, Japanese-Angeleno teens were regarded as “SJs,” and widely envied for their presumed cultural capital.

The opinion that 1980s Japan was the future American was musicians like Ryuichi Sakamoto, cyberpunk novelists like William Gibson (who said in an interview that “modern Japan simply was cyberpunk”), and films like Ridley Scott‘s Blade Runner. The aesthetics of Blade Runner were famously influenced by Tokyo of the 1980s — even if there were no actual Japanese characters in the film. The LED geisha was portrayed by a Korean actress and the only two Japanese-American actors in the film played “Cambodian Lady” and “Howie Lee“). The film’s Nipponized Los Angeles of 2019, in turn, influenced anime films like by urban visions offered in the animes like Neo Tokyo, Bubblegum Crisis, Akira, and Ghost in the Shell.

Meanwhile, the Nipponized Los Angeles was only slightly less futuristic. Case in point — in 1983, the owner of Shayne Hayashi, employed two Japanese-built robot waitrons named Tanbo R-1 and Tanbo R-2 to work in his Pasadena Chinese restaurant, Two Panda Deli. They were retired soon after.

Little Tokyo and Little Osaka (as the Japanese business corridor on Sawtelle Boulevard had come to be colloquially known) were both largely redeveloped in the 1980s. The Japanese Cultural & Community Center was completed in the former in 1985. The Japan-American Theater (now the Aratani Theatre) was completed in 1982. The first location of the Curry House Japanese Curry & Spaghetti chain opened in Little Tokyo in 1983. David Hyun’s Yagura Tower was completed in 1983, which preceded the 1984 opening of Japanese Village Plaza, also designed by Hyun. Across the street, the north side of First Street was designated a National Historic District. Meanwhile, the Alan and Masago hotels were demolished in 1986. In Little Osaka, many of the Japanese businesses along Sawtelle were demolished and redeveloped into office buildings and strip mall.

The last of Los Angeles’s Japanese cinemas, Little Tokyo Cinemas, had a brief run in the late 1980s. With the closure of Kokusai in 1986, the last of the city’s Golden Age Japanese cinemas had closed. The New Linda Lea, by then known merely as the Linda Lea, had switched to Hong Kong martial arts films around 1965. Al Taira and Wilson Liu opened their imposing, fortress-like Yahoan Plaza in Little Tokyo in 1985. In 1987, the two-screen Little Tokyo Cinemas began screening Japanese films produced by Shochiku. By 1990, the entire shopping mall had fallen on hard times. Shochiku pulled out and in June, Terry Boyle and Moto Yokoyama (formerly of the Kokusai) stepped in. Little Tokyo Cinemas gamely soldiered on until October 1990, when the screen of Los Angeles’s last Japanese cinema went dark. Yahoan Plaza was purchased and renamed Little Tokyo Square in 2000 and is currently known as Little Tokyo Galleria.

Japan’s asset price bubble burst in 1991, ushering in the so-called “Lost Decade.” Japanese pop culture no longer dominated in the way that it had in the 1980s, although there were further pop culture inroads. Following a bit of attention given to Pizzicato Five in the mid-1990s, irony-suffused Shibuya-kei briefly troubled the international pop underground. Kiyoshi Kurosawa‘s Cure (キュア), released in 1997, and Hideo Nakata‘s Ring (リング), released in 1998, ushered in the heyday of J-Horror. At the same time, American children supplemented their consumption with Japanese imports and adaptations like Dragon Ball Z, Mighty Morphin Power Rangers (adapted from 恐竜戦隊ジュウレンジャー Kyōryū Sentai Jūrenjā), Pokémon, Sailor Moon, and Yu-Gi-Oh!

By the 1990s, Torrance was so associated with Japanese culture and people that it was sometimes jokingly referred to as “Torrance Prefecture,” the “48th Prefecture,” or “トーランス.” Nijiya Market, after being founded in San Diego, had relocated its headquarters to Torrance. It was also in Torrance that Mitsuwa Marketplace established its headquarters. In 1991, Torrance Eastgate Plaza opened, a shopping center substantial enough to compete with the entire Japantowns of other American cities. Coco Ichibanya would later open its first mainland US location in Torrance.

In Little Tokyo, the Japanese American National Museum opened in 1992 on the site previously occupied by Nishi Hongwanji Temple. In 1994, Emperor Akihito, the son of Hirohito, and Empress Michiko visited Los Angeles — making time to visit Little Tokyo and Keiro Retirement Home in Boyle Heights. Eric Nakamura and Martin Wong launched the popular Asian and Asian-American pop culture magazine, Giant Robot in 1994. At the height of the Giant Robot empire, there was the Giant Robot store in Little Osaka, the art gallery, GR2, and a restaurant called gr/eats. It was Little Osaka that Hurry Curry of Tokyo chose to open its first location. It was also Little Osaka where Japanese cream puff chain Beard Papa opened its first Los Angeles location in 2006. All definitely contributed to the perception of Little Osaka as a younger, trendier, and hipper alternative to Little Tokyo.

In 1999, Tuesday Night Café was founed by multi-disciplinary artist, writer, actor, arts educator, and community organizer Traci Kato-Kiriyama. Tuesday Night Café is an Asian-Pacific Islander arts event that takes place on the first and third Tuesday of each month from April to October in the Aratani Courtyard at the Union Center for the Arts in Little Tokyo. It grew out the earlier project, Art Attack, formerly held one a year in Filipinotown. It is, today, the longest-running Asian American mic series in the country.

The birth rate in Japan had been dropping for decades but in 2007 the population began to decline (although at 126.8 million, its exactly where it was in 2000). Meanwhile, the Japanese population of Los Angeles County had grown to 148,319 (the city’s population reached 111,349). In 2000, Takeshi Kitano released Brother, a film in which he played Yamamoto, a yakuza who is sent from Japan to Los Angeles where he forms an alliance with the Little Tokyo yakuza.

Japanese music continued to make in-roads in Los Angeles and beyond. In 2000, DJ Soju  (Christopher Graper) launched a series of parties, called Par Avion, which in 2001 became a regular club night at Hollywood’s now-defunct AlterKnit Lounge and helped popularize global pop music to Angeleno audiences (especially former Britpoppers, it seems), including many Japanese artists like Kahimi Karie, Takako Minekawa, and Towa Tei. Japanese acts including Pine*Am and The Aprils performed there live. It was also in 2004 that Fullerton-born singer Gwen Stefani hired a group of Japanese and Japanese-American back-up dancers known as the Harajuku Girls, inspired by the street fashions of Tokyo’s Harajuku district. In 2008, the now-defunct Second Street Jazz Club began hosting Tune In Tokyo — a club night propelled by an eclectic soundtrack of Super Eurobeat, J-pop, pico-pop, and visual kei. Attendees dutifully dressed like ganguro, gyaruo, lolitas, and representatives of other Japanese style subcultures.

(Christopher Graper) launched a series of parties, called Par Avion, which in 2001 became a regular club night at Hollywood’s now-defunct AlterKnit Lounge and helped popularize global pop music to Angeleno audiences (especially former Britpoppers, it seems), including many Japanese artists like Kahimi Karie, Takako Minekawa, and Towa Tei. Japanese acts including Pine*Am and The Aprils performed there live. It was also in 2004 that Fullerton-born singer Gwen Stefani hired a group of Japanese and Japanese-American back-up dancers known as the Harajuku Girls, inspired by the street fashions of Tokyo’s Harajuku district. In 2008, the now-defunct Second Street Jazz Club began hosting Tune In Tokyo — a club night propelled by an eclectic soundtrack of Super Eurobeat, J-pop, pico-pop, and visual kei. Attendees dutifully dressed like ganguro, gyaruo, lolitas, and representatives of other Japanese style subcultures.

Even as the Japanese population of grew — and despite a newfound obsession with ramen amongst non-Japanese food fadsters — the 2000s could largely be said to have belonged to Koreans and Korean-Americans. Koreatown is the most densely-populated neighborhood — let alone ethnic enclave — in Los Angeles and Little Tokyo was not immune to its rise. Several Little Tokyo businesses, markets, and properties were purchased by Koreans and the Little Tokyo Towers retirement community became home to a growing number of Korean seniors. There were, predictably, tensions but from them arose a series of inter-ethnic collaborations, including a harmony concert, the formation in 2008 of the Little Tokyo Korean and Japanese Better Relations Committee, the launch of a bilingual newsletter, called Bridges. The following summer, Little Tokyo was the site of the Little Tokyo Korea Japan Festival, which featured both Japanese and Korean dance, music, and films.

Navigating business challenges, in comparison, proved for Japanese corporations occasionally more fraught. In 2004, Japan’s FamilyMart chain of convenience stores tried to enter the American market through Los Angeles with the launch of Famima!! Plans to expand to 220 stores stalled at 20 and by 2015, the last Famima!! had closed. In 2006, Nissan’s American headquarters traded the South Bay for Central Tennessee, Toyota moved its headquarters from Torrance. In 2014, Toyota would follow, relocating its American headquarters to Texas.

The 2010s also brought new Japanese companies and institutions, though. Muji, after first opening stores in Northern California and New York, opened their first Los Angeles store in 2013. Uniqlo, after opening their first American store in New York in 2006, opened its first Los Angeles stores in 2014. Daiso (株式会社大創産業), founded in 1972 as a street 100-yen shop called known as Yano Shoten, opened its first Los Angeles location in 2014, following store openings in Seattle and San Francisco. Hello Kitty had been a presence in Southern California since the 1970s, supported by its chain of Sanrio Surprises stores. It was in 2014, however, that the world’s first Hello Kitty Con took place, naturally in Little Tokyo.

Naturally, Los Angeles has produced its own Japanese-American clothing and products. Ricky Takizawa opened the first location of the Popkiller boutique in 2003 on Sunset Boulevard in Sunset Square. The Little Tokyo location followed in 2006. It’s mostly known for its T-shirts, many of which are designed by Japanese artists, and all of which are manufactured in a warehouse in the Arts District. Later in the decade, clothing designer Mina Taira sold her designs at a store called Momo. In 2019, clothing designer Michelle Hanabusa launched a local streetwear brand, Uprisers, which was inspired in part by the “Gidra Sisterhood.”

In 2015, Japanese company Don Quijote (which purchased Marukai in 2013) rebranded, redesigned, and reopened most of its markets as Tokyo Central. In 2016, former Marukai owner Hidejiro Matsu returned to Metro Los Angeles with his new Seiwa Market chain. In 2017, Japan House (Los Angeles) opened, following the establishment of Japan Houses in São Paulo and London. Japan House is a project of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the purpose of showcasing Japanese products and culture. Meanwhile, another Japan-via-New York food fad arrived in Los Angeles when a matcha craze erupted, spawning a handful of matcha bars (although Matchabar closed in 2019).

Perhaps one of the most surprising (but welcome) Japanese cultural developments of the 2010s was the unexpected revival of city pop — was the shiny, upbeat soundtrack to Japan’s economic miracle, something of a counterpart to shoulder-padded British sophisti-pop. The Japanese genre, which flourished in the 1970s and ’80s, had all but vanished during the Lost Decade. Around 2014, it began appearing again, in online mixes and with artists creating new music in the vein of the old. In December 2018, two city pop club nights quietly sprang up in Los Angeles. At a Downtown “micro-gallery,” Capsule Corner, two of the DJs from Tune in Tokyo (Greg Hignight and Del Martin) launched Plastic City. Meanwhile, the duo SunEye (Akiko and Hashim Bharoocha) launched Tokyo City Nights in Frogtown‘s Zebulon. Also around December 2019, an all-vinyl city pop night, Timely, began taking place at various venues.

Japanese-Angeleno festivals and observances:

In my admittedly limited experience, the Japanese, on the whole, love festivals. In Japan there are supposedly more than 300,000 traditional matsuri. There are far fewer Japanese cultural events of any sort here — but still too far too many to list. It’s probably not an exaggeration to say that there are dozens of ikebana lessons, taiko concerts, benshi-narrated film screenings, tofu festivals, sake tastings, tea ceremonies, and city pop nights. Different hongan-jis host their own.

- Anaheim Japanese Fair

- Annual Japanese Food & Cultural Bazaar

- Cherry Blossom Festival|Monterey Park

- Japan Film Festival Los Angeles

- Japanese Food Expo

- Los Angeles Anime Film Festival

- Los Angeles Tanabata Festival

- Natsumatsuri Family Festival

- Nisei Week

- Obon

- Oshogatsu in Little Tokyo

- Setsubun

Japanese-Angeleno chefs:

- Niki Nakayama

- Hiroyuki Urasawa

- Keizo Seki

- Ken Namba

- Osamu Fujita

- Shigeru Kudo

- Yoko Hasebe

- Yoya Takahashi

Japanese-Angeleno Architects:

- Daisuke Dike Nagano (1921-1965)

- Fred Hifumi (1928-present)

- Hideo Matsunaga

- Kazumi Adachi (1913-1992)

- Kazuo “Kaz” Nomura (1921-1978)

- Kiyoshi Sawano (?-2007)

- Toshikazu Terasawa (1923-present)

- Yos Hirose (1882-1963)

- Y. Tom Makino

Japanese-Angeleno landscape architects and garden designers (or who at least worked in Los Angeles):

- Koichi Kawana (1930-1990)

- Makoto Hagiwara (1854-1925)

- Nagao Sakurai (1896-1973)

- Ryozo Kado

- Shigeo Takayama (1916-2010)

- Shinichi Maesaki

- Takeo Uesugi (1940-2016)

Japanese-Angeleno dancers:

- Bonnie Oda Homsey

- Carrie Ann Inaba

- Diane Mizota

- Fujima Kansuma

- Hokuto “Hok” Konishi

- Jadagrace

- Jennifer Kita

- June Watanabe (1930-2018)

- Karin Tatsuoka

- Leo Matsuyama

- Michio Itō (1892-1961)

- Naoyuki Oguri

- Reiko Sato (1931-1981)

Japanese-Angeleno writers:

- Akilah Nayo Oliver (1961-2011)

- Amy Uyematsu (1947-1923)

- Brandon Shimoda

- Christine Kitano

- Denise Uyehara

- Edward Sakamoto

- Elisabeth Uyeda

- Garrett Hongo

- Hanya Yanagihara

- Hiroshi Kashiwagi

- Hisaye Yamamoto

- Jack Fujimoto

- Jen Yamato

- Miya Iwataki

- Momoko Iko

- Naomi Hirahara

- Nina Revoyr

- Samantha Masunaga

- Sesshu Foster

- Shigeo Takayama (1916-2010)

- Teresa Watanabe

- Traci Kato-Kiriyama

- Yone Noguchi (1875-1947)

- Yosuke Kitazawa

- Yukikazu Nagashima

- Wakako Yamauchi (1924-2018)

Japanese-Angeleno Musicians (and Sound Artists):

- Akiko Bharoocha

- Alan Nakagawa

- Dan Kuramoto

- Dane Matsumura

- Danny Yamamoto

- Dave Iwataki

- Devon Tsuno

- Glenn Horiuchi (1955-2000)

- Jean Paul Yamamoto

- Johnny Mori

- June Kuramoto

- Kevin Nishimura

- Key Kool

- LA Koto Ensemble

- Lee Takasugi

- Los Angeles Taiko Ichiza

- Les Sewing Sisters

- Lisa Yoshida

- Los AKAtombros

- Lun*na Menoh

- Makoto Taiko

- Margaret “Machun” Sasaki-Taylor

- Mia Matsumiya

- Mike Shinoda

- Miki Saito

- Mimi Star

- Nancy Sekizawa

- Olive Kimoto (Liquid Mirror)

- Paul Susumu Togawa (1932-2018)

- Peter Hata

- Saori Mitome

- Scott Nagatani

- Shihiro

- Shinichiro “Shin” Kawasaki

- Suki San

- Taiji Miyagawa

- Taku Takahashi

- Teri Kusumoto

- Toshiko Akiyoshi

- Tracy Wannomae

- Visiting Violette

- Yoshiki

Japanese-Angeleno organizations and services:

- California Association of Japanese Language Schools

- Consulate-General of Japan in Los Angeles

- East San Gabriel Valley Japanese Community Center

- Gardena Valley Japanese Cultural Institute

- Go Little Tokyo

- Hollywood Japanese Cultural Institute

- The Ikenobo Ikebana Society of Los Angeles

- JBA Japan Business Association of Southern California

- Japan Alliance

- Japan America Society of Southern California

- Japan House (Los Angeles)

- Japan National Tourism Organization

- Japanese American Bar Association

- Japanese American Citizens League

- Japanese American Citizens League — Pacific Southwest District

- Japanese American Cultural & Community Center

- Japanese American National Museum

- Japanese Chamber of Commerce Foundation

- Japanese Evangelical Missionary Society

- Japanese Food Culture USA

- The Japan Foundation — Los Angeles

- Japanese Language Scholarship Foundation

- Japanese Languages School Unified System

- The Japanese Restaurant Association of America

- Japanese Student Association of USC

- The Japanese Studies Center & Japanese Student Association

- Keiro Retirement Home

- Little Tokyo Historical Society

- Little Tokyo Service Center

- The Pasadena Japanese Cultural Institute

- San Gabriel Japanese Community Center

- San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center

- Terasaki Center for Japanese Studies

- Urasenke Tankōkai Los Angeles Association

Japanese-Angeleno Artists:

- Aisuke Kondo

- Ako Castuera

- Amy Inouye

- Ben Sakoguchi

- Benji Okubo (1904-1975)

- Cindi Kusuda

- Clement Hanami

- Daisuke Okamoto

- Gajin Fujita

- George Takamura

- Glenn Kaino

- Heisuke Kitazawa (aka PCP)

- Hideo Date (1907-2005)

- Hideo Sakata (1935-2023)

- Hirokazu Kosaka

- Hiromu Kira (1898-1991)

- Hitoshi Yoshida (1951-1990)

- Isamu Noguchi

- Isao Hirai

- J.T. Sata (1896-1975)

- Jerry Matsukuma

- Junichiro Hannyo

- Karin Higa (1966-2013)

- Kaz Oshiro

- Kazuko Kayasuga Matthews

- Kim Yasuda

- Kristine Aono

- Linda Nishio

- Mark Nagata

- Masami Teraoka

- Matsumi Kanemitsu (1922-1992)

- Mike Saijo

- Misato Suzuki

- Nancy Uyemura

- Naoshi Sunae

- Nobuho Nagasawa

- Patrick Nagatani

- Rob Sato

- Roger Yanagita

- Ruth Asawa (1926-2013)

- Sawako Shintani

- Shinkichi Tajiri (1923-2009)

- Shino Arihara

- Shinsaku Izumi (1880-1941)

- Sonya Ishii

- Taro Yashima (1908-1994)

- Thomas Suriya

- Tony Osumi

- Toshio Aoki (1854-1912)

- Toyo Miyatake (1895-1979)

- Zen Sekizawa

Japanese-Angeleno Actors, Filmmakers, Film Crew, &c:

- Aaron Takahashi

- Aiko Tanaka

- Akira Takayama

- Ako

- Al Kikume

- Albert Nozaki

- Ann Kaneko

- Anne Misawa

- Atsuko Okatsuka

- Bill M. Ryusaki (1936-2016)

- Bill Saito (1936-2012)

- Bob Okazaki (1902-1985)

- Brady Tsurutani

- Brian Tochi

- Brittany Ishibashi

- Candace Kita

- Caroline Junko King

- Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa

- Chris Tashima

- Christina Kokubo (1950-2007)

- Clyde Kusatsu

- Dale Ishimoto (1923-2004)

- Dan Koji

- Dann Seki

- Danny Kamekona (1935-1996)

- Darin Fujimori

- Denice Kumagai

- Diana Lee Inosanto

- Diane Takei

- Douglas N. Hachiya

- Edo Mita

- Emily Kuroda

- Emily Woo Yamasaki

- Emily Yoshida

- Eriko Tamura

- Frank Kumagai (1919-1979)

- Frank M. Seki

- Frank Tokunaga

- Garret Sato

- Gedde Watanabe

- George Kuwa (né Keiichi Kuwahara) (1835-1931)

- George Matsui

- George Takei

- Glenn Kubota

- Goh Misawa (1928-2007)

- Goro Kino (aka Gordo Keeno) (1877-1922)

- Greg Watanabe

- Gregg Araki

- Gregory Hatanaka

- Hana Hatae

- Harold Sakata (1920-1982)

- Hayley Kiyoko

- Henry Kotani (aka Hanoki aka Henry Katoni) (1887-1972)

- Henry Nakamura

- Hidekun Hah

- Hideo Inamura (1926-2015)

- Hira Ambrosino

- Iris Yamaoka (1910-1960)

- Jack Yutaka Abbe (1895-1977)

- James Saito

- James Shigeta

- James Yagi (1923-1997)

- Jeanne Mori

- Jeanne Sakata

- Jeff Imada

- Jerry Fujikawa (1912-1983)

- John Fujioka

- John Koyama

- Jordan Nagai

- Junya Sakino

- Keenan Shimizu

- Keisuke Hoashi

- Ken Narasaki

- Ken Ochiai

- Kerry Yo Nakagawa

- Kevin Yamada

- Kimi Takesue

- Kimora Lee Simmons

- Koji Steven Sakai

- Komato Sungata (aka Komato Sunata)

- Kunihiko Nanbu (aka K. Nambu)

- Lane Nakano (1925-2005)

- Lane Nishikawa

- Larry Kitagawa

- Lee Kolima (1920-1995)

- Lena Yada

- Linda Sato

- Louis Ozawa Changchien

- Mako (1933-2006)

- Marika Yamato

- Marilyn Tokuda

- Masi Oka

- Matthew Hashiguchi

- May Takasugi (1915-2007)

- Maya Erskine

- Michael Hasegawa

- Michi Kobi (1924-2016)

- Miki Yamashita

- Miko Mayama

- Miiko Taka

- Misao Seki

- Miyoshi Jingu (1893-1969)

- Miyoshi Umeki (1929-2007)

- Mr. Yoshida

- Naomi Matsuda

- Nobuko Miyamoto (aka Joanne Miya)

- Otto Yamaoka (1904-1967)

- Pam Hayashida

- Paris Tanaka

- Pat Morita (1932-2005)

- Pat Suzuki

- Pete G. Katchenaro

- Peter Yoshida

- Reiko Sato (1931-1981)

- Renee Tajima-Peña

- Robert Ito

- Robert Kino (1921-1999)

- Robert Kinoshita (1914-2014)

- Robert A. Nakamura

- Ron Nakahara

- Ronald Yamamoto

- Saachiko Magwili

- Sab Shimono

- Sara Tanaka

- Sessue Hayakawa

- Sharann Hisamoto

- Sharon Omi

- Shin Koyamada

- Shinko Isobe

- Shireen Nomura

- Shizuko Hoshi

- Shuji Joe Nozawa (aka Fuji) (1922-2008)

- Shuko Akune

- Sojin (ne Sôjin Kamiyama) (1884-1954)

- Stan Egi

- Steven Okazaki

- Susan Fukuda

- Suzy Nakamura

- Tadamori Yagi

- Tadashi Nakamura

- Takayo Fischer

- Tamlyn Tomita

- Teru Shimada (1905-1988)

- Tetsu Komai (1894-1970)

- Thomas Isao Morinaka

- Tokuko “Taku” Nagai Takagi (1891-1919)

- Toshia Mori (1912-1995)

- Toyo Fujita (1893-1959)

- Traci Toguchi

- Troy Terashita

- Tsuru Aoki (1892-1961)

- Tsuruko Kobayashi

- Tôgô Yamamoto

- William Yokota

- Yasuko Nagazumi

- Yoi Tanabe

- Yoshimi Imai (1925-1993)

- Yoshio Yoda

- Yuji Okumoto

- Yuki Shimoda (1921-1981)

- Yukio Aoyama (1888-1939)

- Yuta Okamura

- Yvonne Shima

FURTHER READING & VIEWING

- Daitetsu Shinbun/Heimin/Rafu Mainichi Shinbun

- Densho Encyclopedia

- Discover Nikkei

- 同胞 (1938-1942)

- Furusato – The Lost Village of Terminal Island (dir. David Metzler, 2006)

- Gidra (1969-1974, 2019-present)

- Happy Life in Los Angeles

- Kadaeのロサンゼルス K-TOWN LIFE【LAグルメとコリアタウン】

- Kadaeのロサンゼルス麺探訪!!

- Healthy Living in Los Angeles

- Japanese Americans of the South Bay by Dale Ann Sato, 2009

- JapanUp!

- Lighthouse ロサンゼルス

- Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo by the Little Tokyo Historical Society, 2010

- Mayumi’s LA Happy Life

- 昔話しですが、Los Angelesに住んでました。

- Rafu Ashai

- Rafu Maru Maru Chinbun/羅府団団珍聞

- Rafu Nichibei (1922-1931)

- Rafu Shimpo

- “Redefining Asian America: Japanese Americans, Gardena, and the Making of a Transnational Suburb” by Ryan Reft, 2014

- さとみるくのアメリカ日記

- Sawtelle: West Los Angeles’s Japantown by Jack Fujimoto, 2007

- Shin Nichibei (1947-1966)

- Soy Paper

- SurveyLA: Japanese American Historic Context by the Office of Historic Resources, 2018

- Wasabi Press

- WeeklyLALALA

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always seeking paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, Los Angeles County Store, the book Sidewalking, Skid Row Housing Trust, and 1650 Gallery. Brightwell has been featured as subject in The Los Angeles Times, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, and on Notebook on Cities and Culture. He has been a guest speaker on KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, at Emerson College, and the University of Southern California.

Brightwell is currently writing a book about Los Angeles and you can follow him on Ameba, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram, Mubi, the StoryGraph, and Twitter.

You sure did a lot of research! Have you ever thought of or already put your work into a book?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am slowly working on a book — or books. Probably makes more sense than the blog format, to be honest!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Looking forward to reading your books! I am working on some myself! Good luck and enjoy writing them! Hope you get lots of quality writing time!

LikeLike

Awesome work! I’ll finish reading this weekend but I think I found a typo: “By 1888, there were approximately 70 Japanese living in Japan…”

P.S. Thanks for the link!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Haha oops! Thanks for catching that… and I’m happy to provide a link to Soy Paper — yours is one of my most frequently consulted and highly valued websites. Without it I’d have missed out on the silent film screenings with benshi that took place at the Hammer. That was incredible!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the read! It was a great way to occupy a night shift.

LikeLiked by 2 people

TL;DR, you lost me at the first image where even at first glance two of the images in the collage are of Koreatown & Chinatown

LikeLiked by 1 person

Um, did you even read the words “Pan-Asian Metropolis” or was even that too much to ask? The collage does include images of Chinatown and Koreatown… and Little Tokyo, Cambodia Town, and Little Saigon. Hence, “pan-Asian.” But, you know, keep commenting on things you haven’t read — it makes you look smart and not at all a waste of your time!

LikeLiked by 2 people