INTRODUCTION

The other day, I explored Elysian Park, because it was leading in the California Fool’s Gold neighborhood poll. When I created that poll, I hadn’t yet created Southland Parks. While Elysian Park is sometimes described as a neighborhood (e.g. the Los Angeles Times’ Mapping Los Angeles and Wikipedia) and there are a few homes within the park — remnants of the mostly demolished neighborhood of La Loma and Bishop, the still extant neighborhood of Solano Canyon, and a growing number of tents — Elysian Park is definitely a park, and thus I’m publishing it as part of Southland Parks.

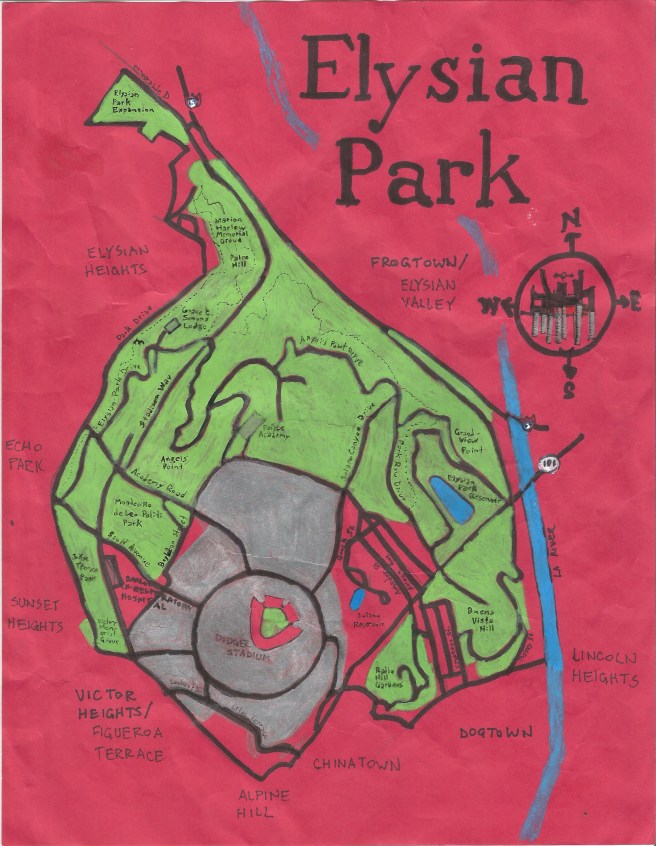

MY MAP OF ELYSIAN PARK

After I began to a modest amount of attention for my neighborhood maps, one of the questions I was most commonly asked was what was the first map that I drew. The answer I gave turned out to be wrong, as was eventually pointed out by my friend Natalya, with whom I used to regularly hike in Elysian Park. She was living on Lilac Terrace, near the park’s southern edge. All of our hikes followed the same course. We entered the park at the Victory Memorial Grove, hiked to the Marian Harlow Memorial Grove, and then retraced our steps back to her bungalow court.

One day, whilst gazing across the park at Peter Shire’s Frank Glass and Grace E. Simons Memorial Sculpture, I remember asking her if she wasn’t at all curious about the rest of the park. I don’t remember her exact answer but I think that the gist was that she was scared of getting lost. Although 2001 doesn’t seem that long ago, there were not yet smartphones (except in Japan) and there was no Google Maps. In fact, before “Googling” was a verb, most internet searches were conducted with AltaVista and though primitive, AOL’s MapQuest was the most popular online mapping service. There were also zero maps or trail markers within the park and so I set about mapping the park the old fashioned way, by exploring it, and that became my first Los Angeles map.

When I was young, I drew maps of the area surrounding our home in rural Missouri. When, after my mother’s death, I briefly lived with my father and his wife, I made maps of the suburban streets around their home in Florida. Around 2009, I began drawing maps as part of my explorations. I made a new Elysian Park map (I’m not sure where the original is, or even if it still exists) using red paper, in (I think) 2010. I found that, for whatever reason, my scanner struggled with red paper and additionally, that green and blue ink both looked muddy and dark. It may’ve been the last red map that I drew. Eight years later, I’ve gone back to it using oil paint to make the green and blue stand out more clearly.

Seventeen years after originally mapping Elysian Park, I returned to explore. There are still zero maps within the park and no trail markers. There is a map on the City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks website now, although whatever the shortcomings of my map, it is hopefully not as laughably bad. On the right is, in fact, the map of Elysian Park provided by the website of the Department of Recreation and Park — apparently, a scanned photocopy of some an area of the park — turned sideways and with unexplained highlighting.

are still zero maps within the park and no trail markers. There is a map on the City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks website now, although whatever the shortcomings of my map, it is hopefully not as laughably bad. On the right is, in fact, the map of Elysian Park provided by the website of the Department of Recreation and Park — apparently, a scanned photocopy of some an area of the park — turned sideways and with unexplained highlighting.

It’s sadly typical of the shoddiness with which the city mishandles Elysian Park which, though I enjoyed revisiting, frequently had me feeling frustrated, annoyed, and cranky.

HISTORY

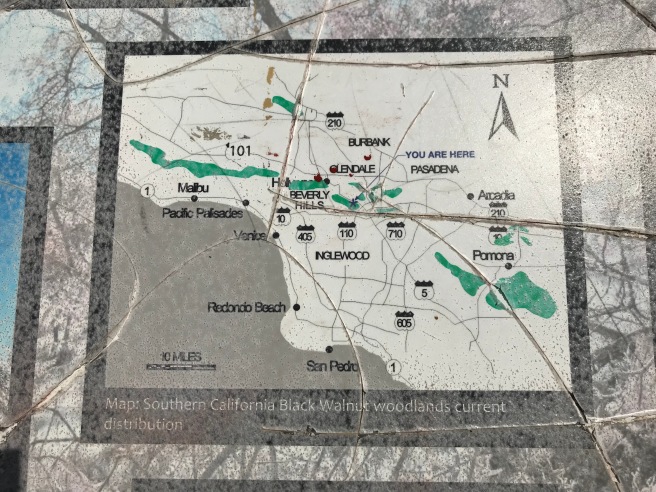

Elysian Park is located within a chain of prominences known as the Elysian Hills. During my exploration, I saw Audobon’s cottontail rabbits, black-headed grosbeaks, fox squirrels, mourning doves, ravens, red-tailed hawks, Southern alligator lizards, Western scrub jays, and a Western tiger swallowtail. Native species historically found there include ash-throated flycatcher, Bewick’s wren, coyotes, crows, gopher snakes, gray foxes, grizzlies, Nutall’s woodpeckers, opossums, Pepsis wasps, raccoons, skunks, slender salamanders, Western fence lizards, Western gray squirrels. All, save grizzlies and mountain lions, are still regularly encountered there. The park is also known for its remand populations of native oak and walnut trees which are endemic to California.

Long after the indigenous Chumash vacated most of the interior, the Tongva arrived from the Sonoran Desert roughly 3,500 years ago and established at least two villages — Maaw’nga and Yaanga — near what’s now the park. The Spanish arrived in 1769 and on 2 August, the Portolá expedition set up camp at a site marked by the “Portolá Trail Campsite” plaque and designated California Historical Landmark No. 655. In 1781, the Spanish founded El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles with what’s now Elysian Park located within its four square leagues. Mexico declared independence from Spain in 1810. In 1844, Julian A. Chavez was granted 83 acres (33.5 hectares) of land which came to be known as Chavez Ravine. In 1848, the US defeated Mexico in the Mexican-American War. In 1850 California became a state and Los Angeles incorporated as a city.

During smallpox outbreaks in the 1850s and 1880s, afflicted Angelenos were interred in a hospital in Chavez Ravine. By the 1880s, the hills and valleys were mostly denuded of trees, most cut down for lumber and firewood. The hillside facing the Los Angeles River had been mined for rock and came to be known as “Stone Quarry Hill” or simply “Quarry Hill.” It was widely dismissed as a wasteland unsuitable for development and in 1883, the city tried and failed to find a single buyer for 550 acres (223 hectares) of rugged hills and valleys north of the Pueblo. A cadastral map from 1884 reveals a landscape divided into many smaller tracts and a plot for occupied by the Hebrew Cemetery. It also shows several named canyons, including Cemetery Ravine, Chavez Ravine, Reservoir Ravine, Solano Ravine, and Sulphur Ravine.

On 5 April 1886, 450 acres (182 hectares) were designated “Elysian Park.” Improvements to the park came slowly and arguments were made that it was too “out-of-the-way” to ever be used as a park. Nevertheless, more than 150,000 trees were planted, including deodar cedars, coast live oaks, pines, cypresses, pepper trees — and most numerous of all — eucalypts, which anecdotally still seem to be the park’s most common non-native tree, not surprisingly since they evolved in a similar semi-arid climate and can easily live for more than 250 years.

Development did end up coming to the area in the 1890s. There are still homes in the Solano Canyon neighborhood dating back at least to 1894. The Chavez Canyon Tract was subdivided in 1904, albeit in Sulphur Canyon rather than Chavez Canyon itself — I assume because Sulphur Canyon is no one’s idea of an appealing residential tract name. Just south of Solano Canyon, the community of La Loma arose. In 1913, a lawyer named Marshall Stimson subsidized the relocation of about 250 Mexican families from the floodplains along the Los Angeles River to the Elysian Hills and the neighborhoods of Bishop and Palo Verde were born.

It should be emphasized that these were not semi-permanent shanty towns. A map from 1928 shows communities organized along a standard grid of streets. La Loma had a market and an elementary school — and there was enough community organization that in 1926, residents succeed in pressuring Los Angeles City Council to pass an ordinance which brought to an end the blasting of nearby hillsides by brick companies.

POLICE ACADEMY

The first paid Los Angeles police force was organized in 1869. Before that, the all-volunteer Los Angeles Rangers had enforced the law. In 1924, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) began to meet at an armory in Elysian Park where, the following year, the Los Angeles Police Revolver and Athletic Club (LAPRAAC) had formed.

The Spanish Colonial Revival facilities were later used for pistol and rifle competitions during the 1932 Olympic Games after which, the LAPD acquired use of the athletes’ dormitory, relocated from the Olympic Village in Baldwin Hills and repurposed first as a clubhouse and later as the Los Angeles Police Revolver and Athletic Club Café.

In 1935, an amphitheater and rock garden with pools and cascades was designed by landscape architect Francois Scotti. In 1973, it was designated Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 110. In 1995, the LAPD moved to a dedicated training center in Westchester but the old academy still offers a variety of recreational facilities available to department personnel and their dependents. The café, a gift shop, and gardens are open to the public. I recently visited it for the first time, with my sometime partner in exploration, Mike, and I was surprised to find a space associated with the police so thoroughly tagged and littered with cans of Modelo Especial.

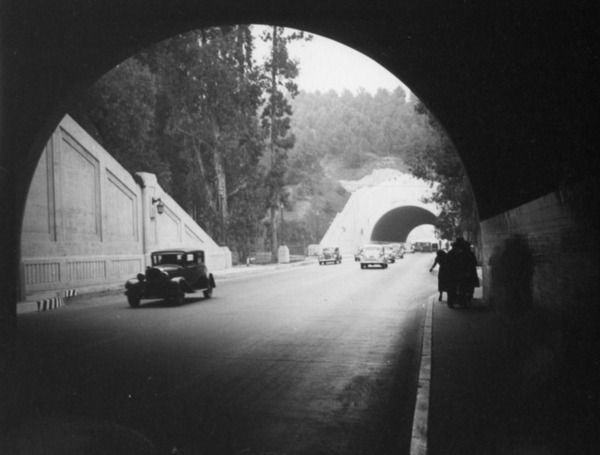

The beautiful, Merrill Butler-designed art deco Figueroa Tunnels were constructed in the 1930s to allow automobiles and pedestrians to pass through the park. Originally, the streets were a modest two-lane design with wide sidewalks. Street lamps shone at the entrances to the tunnels and illuminated their tile-lined interiors. In 1940, the tunnels became part of the newly-opened Arroyo Seco Parkway and, in order to “upgrade” the road, tunnels were cut to accommodate another two lanes of traffic and sidewalks were removed.

In 1937, plans were made to mark the 400th anniversary of Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo’s journey along the coast with the construction of a Pacific Mercado. Instead, in 1938, it became the store of US Naval Reserve Armory, completed in 1940. It was later renamed the Frank Hotchkin Memorial Training Center, after a firefighter who died there on 27 September 1980.

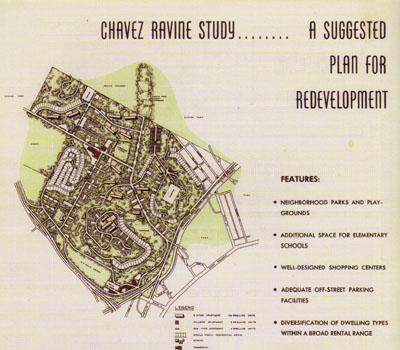

The American Housing Act of 1949 was passed as part of President Truman’s Fair Deal. In 1950, plans were made to provide 10,000 housing units for Angelenos in the Elysian Hills, to be known as Elysian Park Heights. Plans for the 24 thirteen-story projects and 163 low-rises were drawn up by visionary architects Robert E. Alexander and Richard Neutra. Various neighborhoods, including Bishop, Bunker Hill, Dogtown, La Loma, and Palo Verde, were photographed and described as slums in order to allow for the area to be redeveloped. The wording of the law made clear that such redevelopment was meant to include housing for the displaced residents.

In Dogtown, the William Mead Homes were completed in 1942 on a toxic waste dump that wasn’t cleaned up for 52 years. Construction of Bunker Hill Tower only began in 1962. Some Chavez Ravine residents resisted their forced displacement in court but by 1952, most of Elysian Park’s neighborhoods were abandoned. In 1953, C. Norris Poulson based his successful mayoral campaign on the promise to not provide housing for the poor, elderly, war veterans, and those displaced by “slum clearance.” On 9 May 1959, the remaining twenty or so residents of redevelopment area were forcibly evicted — but the redevelopment never came — well, not public housing anyway.

The Brooklyn Dodgers, like so many New Yorkers before and after them, were lured to Los Angeles in 1958. Ground broke on 17 September 1959 for the Praeger-Kavanagh-Waterbury-designed Dodger Stadium. Utterly devoted to the automobile the stadium is surrounded by a parking lot of about 79 hectares — roughly the same size as Chinatown — and there’s even a 76 station — the only automobile service station located on the premises of a major league ballpark. Chavez Ravine Road was renamed Stadium Way. The baseball park opened on 10 April 1962 and was, until 1965, also the home of the Los Angeles Angels, who referred to the stadium, understandably, as Chavez Ravine Stadium rather than Dodger Stadium. Unable to appreciate baseball, I nevertheless explored Dodger Stadium in 2013.

The same decade also bore witness to other significant changes. In 1964, a group of Angelenos formed the Citizens Committee to Save Elysian Park to prevent the construction of the Municipal Convention Center. The Bishops Canyon Landfill opened in 1966. It took three years to reach capacity and it was closed in 1969, filled 130 feet deep with 1,700,000 tons of garbage. In March 1967, Peter Berman helped organize the first of several love-ins, which was attended by about 4,500 hippies.

By the 1970s, thanks in part to decades of white fight to the suburbs, Elysian Park was firmly established as one of the primary public spaces of Mexican-Angeleno life. It seems to remain that very much today, with most Anglo-Angelenos apparently favoring nearby Griffith Park, where adults play golf and tennis, and children ride horses or live steamer trains. Over in Elysian Park — especially on a Sunday — there are families celebrating quinceañeras, children attacking piñatas, and vendors selling duros de harina among other things. On Easter, the grassy picnic areas are littered with the shattered remains of cascarones. The distinction is even apparent in the park’s cruising area, where when I passed through, I exclusively encountered Latinos save for the group of lycra-clad white guys cycling up the hill.

I decided to explore Elysian Park on what turned out to be the day before the autumn equinox. It was, therefore, in the astronomical reckoning, the second to last day of summer. In meteorological reckoning, on the other hand, it was the middle of autumn. To me, it felt like neither, especially, with temperatures climbing to 30 °C. It was also, infamously, the 87th day of smog in a row — the longest stretch of consecutive ozone pollution violations since before 1998, when I first visited Los Angeles. Angelenos were cautioned against even venturing outside but, at the same time, wouldn’t a large park be just the place to find some respite from smogtopia?

Just how large — and how old — a park is Elysian is, surprisingly, not a settled affair. According to the Echo Park Historical Society’s website, “Elysian Park is the city’s oldest public park and, at 575-acres, the second largest after Griffith Park.” Somehow, even this short statement turns out to be demonstrably incorrect on at least two counts.

- It is not the city’s oldest public park. Pershing Square (originally Plaza Abaja), Central Plaza, and Agricultural Park (now Exposition Park) are all older than Elysian Park.

- It is not the second largest park after Griffith as Topanga State Park, Sepulveda Basin Recreation Area, and Hansen Dam Recreation Area all occupy more city acreage than does Elysian Park — even if one includes the adjoining Lilac Terrace Park, Montecillo De Leo Politi Park, Radio Hill, and the so-called Elysian Park Expansion.

Elysian Park is a pretty large park, though, and one which along with Griffith Park accounts for Mideast Los Angeles (MELA) being the least park-poor region in the city. The park is neighbored by the MELA neighborhoods of Elysian Heights, Elysian Valley (Frogtown), Echo Park, Solano Canyon, and Victor Heights; the Downtown neighborhoods of Chinatown and Dogtown; the Northeast Los Angeles neighborhood of Cypress Park; and the Eastside neighborhood of Lincoln Heights.

It is not bordered by Silver Lake, the neighborhood in which I live, but the journey from my door to the entrance of Elysian Park Expansion is 2.4 kilometers — not exactly far, but if I’m going to be hiking for several hours, not exactly close and so I’d happily have chosen Metro’s 96 line if only it arrived, midday, more than twice an hour. Rather than wait thirty minutes, I walked twenty.

As I trudged along Riverside Drive I pondered the park’s relative inaccessibility. For residents of Elysian Heights, it’s quite easy to walk into the park from several points along Park Drive. From Echo Park, there are at least three streets which provide entry — although not one of them has a sidewalk. Victor Heights and Chinatown residents can enter the park near Dodger Stadium where there are sidewalks. A wooden pedestrian bridge used to allow Dogtown residents access to the park via the Cornfields, which were redesigned and remade into Los Angeles State Historic Park. Its design does include a pedestrian bridge, albeit one which connects to neither Dogtown nor Elysian Park, which remains cut off by the Metro Gold Line, which means Dogtown residents wishing to walk to the adjacent Elysian Park must first cross the String Street Bridge to Lincoln Heights, and then cross back over the river at Broadway or by walking up the walkway which runs along the side of the 110 Freeway. Its even worse for residents of Elysian Valley, which are separated from the park by the affliction which is the 5 Freeway. Although Elysian Valley shares the longest border (and a related name) with the park, there are no official connections between the two except for Stadium Way which, though twenty meters wide, has no sidewalks and is treated by the motorists as if it’s yet another freeway.

I entered the Elysian Park Expansion, a two hectare park which opened in 2011, from Riverside, walking up the road (because no sidewalks). At the end of the road was a parking lot, which although completely empty, was not apparently good enough for the woman who drove and parked her vehicle onto a trail.

I poked around the park for a minute before realizing that, despite its name, the Elysian Park Expansion, is physically separated from the park which of which it purports to be an expansion by several homes. Not wishing to climb through their yards, I decided — since it is the only entrance on this side of the park — to make my way along the narrow road verge along the side of Stadium Way and from there to scale the slopes until I reached a trail.

It’s necessary that I stress that walking along Stadium Way, in its current car-centric orientation, is a bad idea, despite the fact that many people obviously do it as there is a sort of foot-worn path, littered though it may be with broken glass and other garbage cavalierly tossed there by motorists. Google Maps doesn’t include the route as a pedestrian option. The path between the road and a retaining wall is so narrow that it is frequently blocked by streetlights, forcing the pedestrian to walk into the curved six-lane speedway. Reaching the end of the retaining wall, I was eager to distance myself from the cars and found another makeshift path, also strewn with litter, which passed through a grove of walnuts, eucalyptus, and poison oak to a ravine which I ascended, although the slope was slippery and shifting thanks to the resident ground squirrels. Finally, I reached a trail, only to backtrack upon discovering that my water can had rolled a little bit down the hill. 45 minutes after leaving my house and voila, I was in Elysian Park and on a trail. Easy-peasy!

The fact that it’s so difficult for anyone not driving an automobile is indicative of embarrassing civic mismanagement. City government officials can talk all they want about environmental concerns and mitigating climate damage but they clearly remain incapable or uninterested in paying more than lip service when so little is done to offer alternatives that don’t require cars. How much work would it be, for example, to paint a crosswalk or extend sidewalks into the park? How much vision is required to see that a bicycle lane in the park might be appreciated? Why is there not a single bus or train which stops within one of the city’s premier public spaces? There are hundreds of parking spaces, though… and what’s up with this record-breaking run of smoggy days, anyway?

After making my way down the dusty trail for a bit, I briefly rested on a tree stump. I was passed by a young woman in black yoga pants, black sunglasses, and a Sisters of Mercy T-shirt (Sisters of Mercy paraphernalia is only available in black, of course). I then headed up a trail through a grove of snags before reaching Marion Harlow Memorial Grove, where all of Natalya’s and my walks used to take us. I don’t know who Marion Harlow is and there’s no plaque informing the visitor, nor are there the sorts of tags you’d expect in this arboretum-like setting. I recognized, however, drought tolerant imports including jade, aloe, and bottle brush; natives like agave, prickly pear, and yucca; and flowers like more commonly associated with yard landscapes like geraniums. There’s a spigot there, and water bowls used by thirsty dogs. I filled up my bottle with water and emptied it into my stomach several times. I washed the blood from my scratched arms and dirt from my face. The Sisters of Mercy fan jogged passed me and, refreshed and rehydrated, I resumed my ramble.

I spied another visitor in a rock band T-shirt, this time a Motörhead fan (another band whose paraphernalia comes only in black). I ended up seeing him several times throughout the day, his gaze in every case cast toward the screen of his smartphone. These sartorial choices of these black-clad visitors struck me as odd on such a hot day, when I next spied a man whose choice of clothing and strange behavior made me wary. A man in blue jeans and a long-sleeved button-up shirt ran up a hillside wielding a large stick which he maniacally then struck against a trashcan. As I approached him, I double checked that I was carrying a knife and, perhaps realizing how strange his behavior appeared to the sane, he politely greeted me as I walked past him.

In the distance, gunfire erupted in waves from the police academy firing range, sounding to my ears like the 18th century battle scenes of movie where soldiers walk bravely and stupidly into enemy fire. When I made my first map of Elysian Park, it included a large wooden condor, which I remember noticing hung high in the branches of a tree. Not having in my possession that map, I tried to remember where it had been. I never saw it — although I did count about a dozen red-tailed hawks — although the thought crossed my mind that maybe it was the same hawk over-and-over, following and haunting me like “The Man” in the film, Carnival of Souls.

I stopped to eat the lunch I’d packed in the Chavez Ravine Arboretum, a collection of trees planted by the Los Angeles Horticultural Society in 1893. New trees continued to be added into the 1920s. 35 trees were planted in 1993 to mark the arboretum’s centennial and today there are about 138 species represented there. In 1967, it was designated Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 48. Some of the signage was so tagged that it was rendered unreadable.

After lunch, I walked around the fenced-off perimeter of the Grace E. Simons Lodge. Ever since first stumbling across this private event space, with its nearly opaque jade green waters, I’ve always regarded it with curiosity. Once I found a hole in the fence and had a closer look. Several years ago, some friends had their wedding there so I got to explore it without fear of being arrested for trespassing. Grace E. Simons, it turns out, moved to China and married a communist organizer named Frank Glass before the tow settled in Echo Park in 1939. Simons was an editor at the famous black newspaper, The California Eagle. In 1965, she and the Citizens Committee to Save Elysian Park and led efforts to stop the construction of a convention center inside Elysian Park. She later stopped efforts to add oil wells, condominiums, and an airport to the park. Simons died in 1985 at the age of 84. After her passing, the Citizens Committee to Save Elysian Park continued her efforts, halting construction of a second stadium in the 1990s.

I next headed across Stadium Way, to hike along a longish trail the parallels the 5 Freeway. Hiking along this stretch, I didn’t encounter another human soul and, although the feeling of isolation wasn’t altogether unwelcome, it was also somewhat shattered by the constant road or the freeway. Although the interstate is about 100 meters below the trail, a decibel reading registered the noise at 81.5 decibels — about the same volume as a blender. Imagine going for a hike with the loudest of kitchen appliances screeching in your ear and you’ll get the idea.

My next destination was Point Grandview, which offers what its name suggests. I and several others stood (or sat in cars, smoking) and gazed out over the Eastside and Downtown. I next made my way down by the Elysian Park Reservoir. Built in 1903, it holds roughly 200,000 liters of water. In the 1980s, it was decided that open-air reservoirs would either be covered or go underground so that the water wouldn’t be turned cancerous by car exhaust, windblown pollutants, and bird droppings.

There were, predictably, protests, by those who claimed that covering the concrete-lined basin, surrounded by a razor-wire-topped chainlink fence, would ruin its aesthetic appeal. In the end, the aesthetic position lost to the position that water drunk by Boyle Heights, Chinatown, Echo Park, Lincoln Heights, and Mount Washington shouldn’t cause cancer and around 2012 it was covered.

After passing the reservoir, I made my way up along Academy Road to Angel’s Point, a hilltop on which stands the aforementioned Frank Glass and Grace E. Simons Memorial Sculpture. It was designed by artist Peter Shire and installed in 1994. Its appearance is that of a sort of industrial, post-modern gazebo topped by a wind turbine — unmistakably a product of the 1990s and irresistible to taggers.

From Angel’s Point, I descended the hill and weaved through traffic at the busy intersection of Stadium and Academy (where, of course, there’s no crosswalk). I next headed south past the parking spaces which on Sundays are usually occupied by lowriders. Stadium Way is lined with a row of Canary Island Date Palms, planted around 1895. Today many are afflicted with a fatal fungus — or have already been felled by it. Simons’s old organization, the Citizens Committee to Save Elysian Park have seen to the replanting of some Chilean Wine Palms in 2014. Neither plant is native to the region and, since they are different species planted decades apart, their original aesthetic effect is compromised. Knowing what we now do about the complex symbiosis of native flora, fauna, and fungi — and because palms are basically just weevil-incubating roof rat nests, it seems to me that the dead exotics should’ve been replaced with grand native oaks or sycamores instead of more pointless palms. Give us another 123 years to get it right.

My next destination was the Barlow Respiratory Hospital. The hospital was opened in 1902 as Barlow Sanitarium by Walter Jarvis Barlow to treat sufferers of tuberculosis. In 1990, the site was designated Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 504. The ten-hectare campus includes cottages, a “guildhouse,” a library, the main hospital, and a community hall which I first visited upon joining the Echo Park Time Bank. It’s still a functioning hospital, used to treat those afflicted with various respiratory ailments, and so I didn’t pass through the campus out of respect to those living and working there.

My last stop during my initial exploration was the Victory Memorial Grove. In August of 1920, a two-hectare field was planted with a field of common poppies to commemorate those who died in the Great War. In 1921, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) installed a one-and-a-half meter tall block of granite block with a bronze plaque dedicated to 21 soldiers who’d had family members in the DAR. On Flag Day of 2017, a restored memorial was rededicated. Most of the original seventeen trees are long gone, however.

After I got home, I realized that there were a few spots that I’d forgotten or overlooked and about a week later I returned with my friend Mike. Years ago we’d both attended a pool party on Boylston Street, all that remains of Bishop and a street whose modest but attractive homes put to lie the notion that the neighborhoods of Chavez Ravine could all be dismissed as “slums.” And lest one think that these homes are newer constructions, nearly all of the nineteen homes along Boylston Street and what’s left of Shoreland Drive (dramatically truncated by the parking lot of Dodger Stadium) were built between 1916 and 1956, the year construction of Dodger Stadium began.

From there we walked past the Elysian Park Adaptive Recreation Center, where there’s a rock with a plaque dedicated to “Los desterrados (the uprooted) former residents of Chavez Ravine, placed by the Palo Verde, La Loma, Bishop Cultural Historical Association on 19 July 1979.”

From there we walked to Solano Canyon, where Amador Street marks what was originally the border between that neighborhood and the neighborhood of La Loma. The homes on the west side of the street, the oldest of which date back to 1906, are the remnants of that neighborhood and like those on Boylston, challenge the notion that the neighborhoods of Chavez Ravine were slums. To the southwest is an area, Radio Hill, that I previously explored in another piece, and so we walked up a ramp to the Arroyo Seco Parkway Walkway, a fence-enclosed, rubbish-strewn walkway which runs between the lanes of the 110 Freeway.

If it seems strange to the reader that a city would carve a city park in two with an interstate freeway, you’re not alone. Originally the park section of the Arroyo Seco Parkway was just a scenic, two-lane street lined with sidewalks. Celebrated municipal engineer Merrill Butler designed three tunnels, fourteen meters in width and 8.6 meters in height, were constructed for Figueroa Street in 1931. A fourth, 230 meters long, opened in 1936. The tunnels were light with street lamps which reflected from tiled walls. The Arroyo Seco Parkway opened in 1940 and the roadway was “upgraded” by removing the sidewalks and adding lanes for cars. In 1943, new westbound lanes opened in a surrender of even more parkland. In 1953, the Arroyo Seco Freeway was renamed the Pasadena Freeway. Its name reverted to the Arroyo Seco Parkway in 2010, but aside from the art deco tunnel entrances, there’s little that’s scenic about the Figueroa Tunnels today. Above them are walnut groves and semi-permanent homeless camps so strewn with garbage that you can’t help but marvel at the park’s neglect.

The southeastern corner of the park contains Buena Vista Hill and the Buena Vista Meadow Picnic Area. Hoping to learn something about them, I performed an internet search. The first entry was not on Wikipedia, as I’d expected, but a site called cruisinggays.com. Google also informed me that related searches for this park include Flex Sex Club, Slammer Sex Club, “hookup spots,” and, most humorously, “trough urinals Los Angeles” which, perhaps, told me all that I needed to know about the area and the men we passed waiting patiently in their parked trucks and vans as other men shuffled around the hillside.

We made another pass near the reservoir, hoping to get a better look from that side, before heading out of the park to get supper.

MORE ELYSIAN PARK

- Elysian Park – City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks

- Chávez Ravine, 1949, a Los Angeles Story by Don Normark (1949)

- Chavez Ravine directed by Jordan Mechner (2003)

- “CityDig: Chavez Ravine in 1868” by Glen Creason (2013)

- “Elysian Park: A Plaza Set in Nature” by James Rojas (2018)

I really appreciate your blog. I love your writing style! Thank you for sharing your love of geography and our beautiful city.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. It’s always so nice to receive encouragement from readers!

LikeLike

If you want or need any information on Victory Memorial Grove I am sort of the unofficial historian.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I could give you way more info on Victory Memorial Grove if you want!

LikeLiked by 1 person

By all means. You can write a comment here, if you like. Thanks!

LikeLike

were a popular way to remember the fallen after WWI. The Los Angeles Examiner first promoted the idea for VMG in Southern California. Just prior Memorial Day 1919, the newspaper convinced the LA Parks Commissioners to adopt a resolution.

If I read the the archives correctly, the original site was where Radio Hill now stands. However, within a year of the dedication, the site was undeveloped except for an initial tree. There were access issues (ones that still plague Radio Hill) which led to the site of VMG being changed in August on 1920 to the current site.

Mary Stilson, one of the prominent landowners of the area (and former State Regent of the Daughters of the American Revolution) donated a portion of her holdings so an entryway could easily access the new VMG. Three Oaks were planted at the new dedication – ones for Ross Snyder, Elizabeth Stevens, and one for all the lost of the war on behalf of the American Legion.

We think the flagpole at the bottom of the hill was put there in late 1920 or early 1921 based on LA Times accounts. The Parks Department also researched placing a memorial plaque displaying a

soldier and sailor grasping hands as a marker at the entryway of the Grove. Julia Bracken Wendt, a local sculptor, took a considerable amount of time to complete her design. By the time she was finished and located a foundry the Commissioners had all changed, and it seems the funding fell through.

Trees were continuing to be planted and dedicated. In a bit of a bait and switch the Parks Department planted them free of charge, but accompanying plaques were required, which cost 50 dollars, a substantial amount for the time. Local war hero Walter Brinkop of the 364th Regiment’s Machine Gun Company bought thirteen trees for all the men under his command lost in battle – which as far as I can tell was the most anyone got at one time. In a change from the original intent of the park, those from beyond the region were also being memorialized here. For a city already full of transplants, it seemed fitting that a memorial park would include those from as far away as Texas and Indiana (Brinkop’s men were mostly from the West, but not all of them were). Records are spotty as to how many trees were eventually planted, but I found a plot #43 issued (I only have about 22 names) – so there might have been at least that many planted — we aren’t sure.

Much like the Parks monument that never materialized, other civic groups like the Lafayette Society and Red Cross discussed erecting memorials, but it seems that none ever followed through. Because of this, the DAR memorial, erected in 1921 symbolically is the centerpiece of Victory Memorial Grove and will remain as such forever.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for this detailed heavily-photographed post. I found it while researching the La Loma neighborhood today. My grandmother was born and raised in La Loma, my grandparents lived there when first married, and my biological father lived there as a baby. I interviewed my grandma last weekend more about growing up in La Loma, and I have found some old maps of those destroyed Chavez Ravine communities that show me exactly where they lived on Spruce, as well as where other family lived in the community. So my husband and I are planning a drive up there soon to wander and hike around. Your post is very helpful and gives me some great ideas. My grandma told me that she visited the area years ago and that the only thing remaining of La Loma are some concrete steps leading up to it, and I think that photo you have of the Solano/La Loma boundary area with steps must be those same steps. So that gives me a great clue of what to look for when there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s great. The destruction of those neighborhoods is such a sad story — compounded by the fact that the homes that were supposed to built to re-house residents never got built. The famous photos documenting the neighborhood show that some of them were pretty rustic, but not much different from the homes in many rural areas of that era. And the few houses that remain in the remnants of those neighborhoods show that most of the homes were pretty typical of many a Los Angeles neighborhood. Have fun exploring!

LikeLike